Coming of Age In The 1990s - Part 2

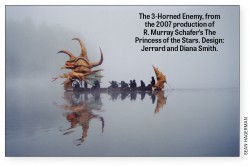

It was 3:40 in the morning. The forest was in absolute stillness, the canoe slipping into the water, barely making a sound. It was a cool September morning on Wildcat Lake in the Haliburton Forest in 1997. My cargo – two condenser microphones and a portable digital recorder – and I were heading out to a floating platform on the far side of the lake, where I would, in the pitch black night, attach the gear to a pre-positioned mic stand bolted to the float, start the recorder, head to the nearest shore, hide with my canoe behind a boulder and await the start of Murray Schafer’s opera, Princess of the Stars. At the same time, my two colleagues, recording engineers David (Stretch) Quinney and Steve Sweeney paddled to two more locations and engaged two more recording positions. We were about a kilometre apart from one another, and we would record several performances of Schafer’s “environmental opera” over the course of a week, to be mixed and assembled for broadcast on our contemporary music show, Two New Hours on CBC Radio Two. That broadcast would eventually, in 1999, win a medal for excellence in performing arts broadcasting at the International Radio Festival of New York.

It was 3:40 in the morning. The forest was in absolute stillness, the canoe slipping into the water, barely making a sound. It was a cool September morning on Wildcat Lake in the Haliburton Forest in 1997. My cargo – two condenser microphones and a portable digital recorder – and I were heading out to a floating platform on the far side of the lake, where I would, in the pitch black night, attach the gear to a pre-positioned mic stand bolted to the float, start the recorder, head to the nearest shore, hide with my canoe behind a boulder and await the start of Murray Schafer’s opera, Princess of the Stars. At the same time, my two colleagues, recording engineers David (Stretch) Quinney and Steve Sweeney paddled to two more locations and engaged two more recording positions. We were about a kilometre apart from one another, and we would record several performances of Schafer’s “environmental opera” over the course of a week, to be mixed and assembled for broadcast on our contemporary music show, Two New Hours on CBC Radio Two. That broadcast would eventually, in 1999, win a medal for excellence in performing arts broadcasting at the International Radio Festival of New York.

1997 had been a remarkable year for the Two New Hours team. In June of that year we recorded and broadcast a concert from the Barbara Frum Atrium in the Canadian Broadcasting Centre, a surround-sound event that featured not only the first authentically staged performance of Harry Somers’ (1925–1999) spatially animated Stereophony, but also the world premiere of Borealis, a work we commissioned especially for the occasion by Toronto composer Harry Freedman (1922–2005). This event was produced in collaboration with Soundstreams’ Northern Encounters Festival, described as, “a circumpolar festival of the arts.” Borealis combined the forces of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, the Danish National Radio Choir, the Swedish Radio Choir, the Elmer Iseler Singers and the Toronto Childrens’ Chorus, all under the direction of conductor Jukka-Pekka Saraste. These combined forces surrounded the audience from the ground floor, up into the various levels of balconies ringing the ten-story atrium. The effect of the music was stunning. Harry Freedman himself considered it one of his finest achievements in writing for large-scale musical forces.

We subsequently presented Freedman’s Borealis to the International Rostrum of Composers (IRC) in Paris in 1998, where it was voted fourth overall among the submissions by the delegates from public radio services in 30 countries around the world, leading to broadcasts in those countries. Harry was very pleased with this accomplishment, comparing it to the experience of “being shortlisted for the Booker Prize.” Naturally, he was also pleased to receive the royalties from those many broadcasts.

Earlier in 1997, another of our CBC commissions, Wonder, a work for soprano, orchestra and electronic sounds by Canadian composer Paul Steenhuisen, had even greater success at the IRC. Wonder had been commissioned in 1995 for the CBC Radio Orchestra in Vancouver. The premiere took place in June of 1996 at the Vancouver International New Music Festival, presented by Vancouver New Music. We presented our production of the work at the IRC in 1997, and not only was Steenhuisen’s composition voted third overall, and broadcast on the participating countries’ public radio programs, but the delegate from Austrian Radio was so impressed by the work that he organized an Austrian performance at the Musikprotokoll Festival in Graz. But it didn’t stop there. Christian Scheib, the same Austrian delegate who had been so impressed by Steenhuisen’s Wonder at the IRC, also commissioned a new work by him, for the esteemed Viennese ensemble, Klangforum Wien. Austrian Radio produced the premiere of the new work, Bread, at the Musikprotokoll Festival, conducted an extensive interview with Paul Steenhuisen, and broadcast the premiere of Bread, along with several more of Steenhuisen’s compositions. Writing to me about our original commission of his work, Wonder, Paul said, “Reflecting on it, the piece has had a nice life for itself. So many good things came from its presence at the IRC, so thanks again for taking it there.”

A few years before that, our production of Chris Paul Harman’s Oboe Concerto, was voted second in the Young Composers category of the IRC. This was in 1994, when first place went to the emerging English composer, Thomas Adès for his famous composition, Living Toys, the work that more or less signalled to the world of contemporary music that a new genius had appeared. Harman, in his typically humble manner, told me that “in retrospect, Living Toys should have been ahead by many, many, many more votes – I consider it to be one of Adès’ best works, among a selection of very good works.”

These examples were typical of what we did throughout the 1990s. We found ways to work in larger-scale, and we dared to encourage Canadian composers to develop and excel, and to feed their creative imaginations with the ambition to create works of significance. And when we submitted these larger works in international forums, such as the IRC or the International Radio Festival of New York, our successes were a clear message that our composers, with the help of CBC Radio Music, were seen to be advancing the art form. Our work developing Canada’s composers was beginning to give them international recognition. Interestingly, all of this development came during a climate of cuts to the CBC’s budget. Harold Redekopp, who was head of CBC Radio Music in the mid 1980s, and then vice-president of CBC English Radio from 1992 to 1998, remarked that, for the relatively modest budget allocated to Two New Hours, we created an enormous amount of good will in the musical community.

One of our principal methods of increasing the impact of our limited budget was through creative partnerships with medium- to large-scale organizations. Once our major orchestras began creating new music festivals, first in Winnipeg in 1992, but soon after in Vancouver, Toronto, Montreal, Kitchener-Waterloo and Windsor, we suddenly had the means to create programming that included many more Canadian orchestral and larger-scale compositions. We found that offering to commission ambitious new works by Canadian composers often provided the key to innovative programming, works such as Chan Ka Nin’s Iron Road, Marjan Mozetich’s Affairs of the Heart, Ann Southam’s Webster’s Spin and Murray Schafer’s Thunder: Perfect Mind, all of which, curiously enough, are now accessible on YouTube. Such initiatives often unlocked resources that had been previously uncommitted by potential partners. The programs we were then able to offer our listeners gave them a ringside seat as the music of the future was created.

David Jaeger is a composer, producer and broadcaster based in Toronto.