“At a very young age I felt that Schumann’s emotional musical language really spoke to me and became very personal to me. The feeling of connection with Schumann’s music was also encouraged by my teacher, Juliette Audibert-Lambert, whose teacher, Alfred Cortot, was a renowned interpreter of Schumann’s and Chopin’s music. Schumann’s music was so special to her that she would assign it as a treat, almost as a reward, for good work, as something for which a student had proven himself worthy!”

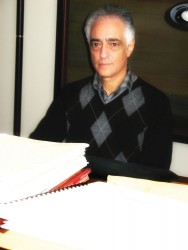

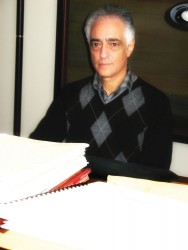

In mid-january I chatted with pianist and University of Toronto music professor, Henri-Paul Sicsic about, among other things, his 2007 recording of Robert Schumann’s Kreisleriana and Fantasie. I was impressed by the CD: no matter how busy the music, and Schumann’s can be very busy, the narrative could always be heard.

In mid-january I chatted with pianist and University of Toronto music professor, Henri-Paul Sicsic about, among other things, his 2007 recording of Robert Schumann’s Kreisleriana and Fantasie. I was impressed by the CD: no matter how busy the music, and Schumann’s can be very busy, the narrative could always be heard.

“I don’t consider Schumann’s music to be particularly difficult to play, but one needs to open emotionally to it. It is not predominantly aesthetic, unlike, for example, Chopin, whose music is much more focused on the beauty of the sound and the culture of the piano. For Schumann, the piano is a vehicle, a means to an end, through which his interior voice and poetry can speak.”

It’s an interesting observation. “We think of Chopin’s music as romantic because it is so beautiful and poetic, but it is more abstract than Schumann’s.”

So if Schumann’s music comes easily to him, whose music does not?

“For me, Beethoven is at the opposite end of the spectrum to Schumann. I feel nurtured by Schumann’s music but challenged by Beethoven’s. Many people have said that Beethoven struggled as a composer whereas Mozart composed effortlessly and even had the music already conceived before he wrote it down. Mozart was playing with already established forms to which he brought a wizardry that no one else could even come close to. Beethoven was always working at redefining those forms, so he was always working from the ground up, not because he was not capable of writing effortlessly — I’m sure he could have if he had chosen to — but through music he was facing his own challenges, questions and struggles.”

So Beethoven’s music, Sicsic says, “always gives me something new, something of a revelation, to find or to overcome, to go empathetically through the same struggle that I feel he was going through as he composed it, meeting forces somehow opposed to the human condition, not going for the obvious.”

Tension, Sicsic says, is a key to Beethoven’s music, persisting through moments of conventional musical resolution. “As for example the chord on which a cadence resolves will be marked ‘subito piano,’ producing a sense of a sudden and unforeseen change in the tension and the direction of the music. Even if we hear his music over and over, it will always feel as if it is rubbing the wrong way. As we move through the development of his music we are gradually reaching a state or a way of being that elevates us beyond our daily struggles.”

Sicsic is not yet well known in Toronto, but there is a chance that after his upcoming, February 27 recital (the first all-Beethoven programme of his career), we will know him a bit better. The programme will consist of the Bagatelles Op.29 and Op.119, the Eroica Variations and the Sonata Op.110. Speaking of the last three piano sonatas, of which Op.110 is the second, he said “The music has become almost dissolved to the point that the texture has been reduced to transparency, like being able to see the stars when there is no light.”

The recital takes place at Walter Hall, increasingly familiar surroundings for Sicsic who was appointed to a full-time teaching position at the U of T’s Faculty of Music in 2007, leaving the University of British Columbia, where he had taught since 1994. Before that he had studied with John Perry at Rice University in Texas and had also been Perry’s assistant.

In 2007, he told me, a new full-time position in piano was created at the U of T Faculty of Music. At the time it was the only full-time position other than what had been William Aide’s position, which is now occupied by Jamie Parker. “I really feel blessed to have been selected for this new position, both because of the strong cultural life of Toronto and to be part of the strong programme we have at U of T and the high standards, which, I think, make it one of the leading programmes in North America.”

Certainly the piano department’s staff bring a wide range of interest and focus to the task. “Jamie Parker is an extraordinary pianist, not only as a member of the Gryphon Trio but also as a soloist. Marietta Orlov, who brings such knowledge, experience and a depth of culture, devotes herself completely to teaching. I focus on performance. Stephen Philcox, who focuses on collaboration with singers, is an incredible talent, and not only as a collaborative pianist but also as a soloist … I remember his wonderful playing and phenomenal sight-reading when he was an undergraduate at UBC …” He continues, describing the particular strengths of all department members, Boris Lysenko, Midori Koga, Lydia Wong … His enthusiasm is manifest. “We may be the only pedagogy programme which is complementing and not undermining the performance side of things … Probably the only comparable programme on the continent is at Michigan State University, where Midori was on the faculty before coming here.”

Sicsic’s pedagogical approach has evolved over time. Born in Algeria of French parents, they moved to Nice, France, in 1962, at the time of Algerian independence. In Nice, as already mentioned, he studied with Juliette Audibert-Lambert. But for a number of years after that he studied on his own. “I tried to contain all that I could remember and experience of my former teachers. This was a very important part of my training, because it enabled me to stand on my own feet, as it were.”

He talks about how important it is for students to “come to their own way,” to learn an entire composition completely on their own, to break “the need, almost an addiction to always asking ‘Am I doing this right?’, to always wanting validation or confirmation that things are ok.”

It’s an ethos built on rising to challenges rather than counting on classical contexts, not dissimilar to the all-Beethoven challenge Sicsic has set for himself February 27 at Walter Hall.

Allan Pulker is a flautist and a founder of The WholeNote, who currently serves as chairman of the company’s board of directors. He can be contacted at allan@thewholenote.com.

If you have a desire to sing, you’d be hard-pressed not to find a place for your voice these days. I’ve been studying community music in Toronto, and my sneak peek at The WholeNote’s 2012 Canary Pages confirmed my own sense of the many opportunities open to singers of all ages, abilities and interests. And that’s just what’s listed in these pages. If the Canary Pages are the tip of a singing iceberg, then there are likely hundreds of places to sing in Southern Ontario. And by all accounts, Ontarians are singing.

If you have a desire to sing, you’d be hard-pressed not to find a place for your voice these days. I’ve been studying community music in Toronto, and my sneak peek at The WholeNote’s 2012 Canary Pages confirmed my own sense of the many opportunities open to singers of all ages, abilities and interests. And that’s just what’s listed in these pages. If the Canary Pages are the tip of a singing iceberg, then there are likely hundreds of places to sing in Southern Ontario. And by all accounts, Ontarians are singing.