The idea that music and theatre often combine in forms other than “musical comedy” was on my mind when I entered the rehearsal hall of the St. Lawrence Centre to talk with  , the co-writers and performers of Two Pianos Four Hands (2P4H), arguably the most successful play in the history of Canadian theatre. Opening on November 2 for a limited run at Toronto’s Panasonic Theatre, before it moves to Ottawa’s National Arts Centre in January, the production marks the show’s 15th year, a remarkable milestone that has seen various incarnations of the piece accumulate close to 4,000 performances in 175 cities (worldwide) and play to upwards of two million people.

, the co-writers and performers of Two Pianos Four Hands (2P4H), arguably the most successful play in the history of Canadian theatre. Opening on November 2 for a limited run at Toronto’s Panasonic Theatre, before it moves to Ottawa’s National Arts Centre in January, the production marks the show’s 15th year, a remarkable milestone that has seen various incarnations of the piece accumulate close to 4,000 performances in 175 cities (worldwide) and play to upwards of two million people.

Though small in size, 2P4H covers a lot of ground as it traces the lives of two boys, Ted and Richard, in their quest for stardom as concert pianists. Working fervently towards their dream, the boys suffer pushy parents, eccentric teachers, repetitive practice, stage fright, nerve-wracking competitions and, finally, their own limitations. After 15 years of tinkling the ivories, they apprehend the gap between the very good and the great, only to arrive at the humbling conclusion that stardom lies beyond their reach.

Although the boys’ goals are specifically musical, their situation is recognizable to anyone who attempts to use training, talent and will-power to achieve greatness in any field. This, suggests Richard Greenblatt, is one of the reasons for the show’s success: “We thought it might just be for music nerds — piano nerds (even worse) — and we found out it wasn’t. People relate the show to their own experience of taking lessons — maybe piano, maybe something else — and of moving on.”

As we chat over soup and sandwiches during the actors’ lunch-break, we focus on the relationship between music and theatre. When I mention that The WholeNote listings section this month characterizes 2P4H as “musical comedy,” Greenblatt shakes his head and says “No, it’s a play about music.” “The piano, specifically,” Dykstra immediately interrupts. “It’s a play about how piano music relates to the lives of the so-called ordinary citizen.” Greenblatt resumes: “It’s a play, but it doesn’t have a traditional play-like structure, except for its two acts. It doesn’t even have characters in a conventional sense. It’s a narrative, but it’s non-linear. There’s a chronology, even though the play circles back on itself, but there’s actually only one scene where we play our own ages.”

The structure Greenblatt describes evolved from improvisations the actors began in 1993 while performing in Chamber Concerts Canada’s “So You Think You’re Mozart.” Both men had trained in classical piano for years, and, as adolescents, achieved near-prodigy status; yet both had switched to acting in their early twenties. Sharing and comparing stories about their past, they were moved to develop a series of sketches that eventually would become the play which, Dykstra is quick to point out, is more “considered” than a collection of mere vignettes. Each actor takes turns playing child versions of the other, while his partner portrays the teachers, adjudicators, parents, etc., that they encounter. And each plays the piano, live on stage, a technique that chronicles their progress.

“It’s the piano-playing that keeps us honest,” Greenblatt says, when I ask him about the requirement that the play’s actors also perform the music. “It keeps us from growing complacent about the show. The piano-playing is the big measuring stick for us, and we’ve set the bar relatively high. Making it the best it can be still is our goal, and our challenge, because it’s not what we do, 24/7.”

In fact, both Greenblatt and Dykstra do so much, 24/7, that it’s unusual for them to find time to do the play: this is their first reunion since 2003 and, according to Greenblatt, it probably is their last. Besides acting in Toronto and across the country, each of them writes, directs and, more to the point of our discussion, composes music for the theatre. Returning to this topic, Greenblatt suggests that “Music in the theatre is another under-valued and under-appreciated design element,” a comment that moves Dykstra to shake his head and emphasize that original composition and sound design “are completely different skills.” He grows passionate as he talks about the way digital technology has furthered the prevalence of musical composition in contemporary performance: “In the same way that video has become less a novelty in the theatre, so has the composition of original music … We are using technology to enhance the imagination in ways that we weren’t able to do before.” Greenblatt concurs. “Composers now have studios in their own homes: Rick Sacks, John Gzowski, John Millard, Thomas Ryder-Payne, Richard Ferren … The situation is very different than years ago when John Roby and Jim Betts were writing music for the theatre.”

Greenblatt’s remark reminds me that he’s been introducing original music into theatrical production for a long time now. As if reading my thoughts, he recalls the score he wrote for his production of Robert Fothergill’s Private Lies at Tarragon Theatre in 1993, noting that the budget for that show wouldn’t allow him to hire a composer. This situation has changed, with more theatres commissioning original music for their productions, a fact that Dykstra’s career corroborates. Within the past year alone, he has composed an original score for the production of Tennessee Williams’ The Glass Menagerie that he directed for Toronto’s Soulpepper Theatre, and another for The Kreutzer Sonata, an adaptation of a one-act monologue by Leo Tolstoy based on Beethoven’s “Kreutzer” sonata, that Dykstra performed for Art of Time Ensemble.

I ask Greenblatt and Dykstra about the music in Two Pianos Four Hands: how did they choose it? Greenblatt is the first to answer: “In both of our cases, we chose music that we have an emotional connection to — like Bach, which is one of the reasons we finish the show with it.” Dykstra adds, “And there’s Mozart, Beethoven, Chopin … and the pop stuff, which changes with each production.” Dykstra’s comment reminds me of a statement he made in 1996 prior to touring the premiere production of 2P4H across Canada, a comment often cited in publicity for the show. “Our greatest fear is that classical musicians will say ‘Well, for actors, they’re pretty good piano players.’ And that actors will say, ‘For piano players, they’re pretty fair actors’.” I ask him if he still experiences that fear now that the play and the production have won plaudits worldwide. “No,” he replies, noting an increase in his confidence as both an actor and a musician. He pauses long enough for Greenblatt to add, “For people who aren’t top-flight musicians, it seems like we’re good but, really, we’re not. Although —” (he glances at Dykstra before turning back to me) “in New York, John Kimura Parker came to see the show and really, really loved it; and so, we, like, started hanging out with him, going to the bar … ” He flashes me a grin. “He kept saying ‘You guys are really classical musicians’.”

When I look to Dykstra for a rejoinder, I am not disappointed. “Manny [Emmanuel] Ax came to see the show just before he appeared on Rosie O’Donnell. He raved about it, said it was the best piece of theatre he ever had seen. Then we went on Rosie …” Now he grins too. “What I like to say is, ‘We’re two of the best piano-players in the neighbourhood’.”

Not to mention, two of the best actors.

As I left the 2P4H rehearsal hall, the idea that music and theatre often combine in forms other than “musical comedy” was still on my mind. When one considers music and theatre together, across the region, options for an evening out are so numerous, they’re daunting. This is especially the case when “music theatre” is viewed as more than “musical comedy” — the genre with which it often is considered synonymous. While a bevy of large-scale “musicals” sweeps onto our stages during the next five weeks to dazzle and delight with music, song and dance, a diverse range of less conventional performances also arrives to expand our notions of music theatre.

Those of you looking for shows that follow more conventional traditions of “musical theatre” couldn’t do better than check out two touring shows that arrive from New York and London boasting excellent productions and stellar reviews. Cameron Mackintosh’s presentation of Mary Poppins, a musical adaptation of the children’s book about a nanny, a chimney sweep and a brace of troubled children, includes new songs as well as those popularized by the film starring Julie Andrews and Dick Van Dyke. It opens on November 10 at Toronto’s Princess of Wales theatre for a run of almost two months, all its magic intact. Directed by Richard Eyre whose production of Noel Coward’s Private Lives starring Paul Gross and Kim Cattrall is currently en route to Broadway, Mary Poppins features spectacular choreography by Matthew Bourne whose ground-breaking production of Swan Lake still unsettles my memory.

Competing for my attention in the category of touring musicals over the next month is Memphis, which premieres at the Toronto Centre for the Arts on December 6 for a three-week run in a production directed by Christopher Ashley. Winner of the Tony Award in 2010 for Best New Musical, the show is notable for its score by D. Bryan, a founding member of Bon Jovi, and its choreography by Sergio Trujillo, well known to local audiences for his choreography of Jersey Boys. Based on actual events, Memphis recreates the underground dance clubs of Memphis, Tennessee, in the 1950s, where a young black singer, itching for a break, teams up with a crusading white DJ at a local radio station. The inter-racial cast delivers an eclectic mix of rock ‘n’ roll, jazz and blues that promises entertaining insights in the tradition of Dreamgirls.

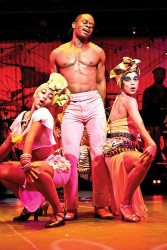

Finally, for an entirely different experience of music and race relations, check out Fela!, a dance-drama depicting the story of Fela Kuti, the Afrobeat pioneer whose life and music is the stuff of legend, in a production that arrived on October 25 and runs till November 6 at the Canon Theatre. Discussing the show, Bill T. Jones, one of America’s most innovative and respected choreographers, says, “One has to experience it as much with one’s hips as one’s ears, eyes and mind.” Given that Jones directed the piece, I could easily accuse him of bias — except that Fela Kuti’s soulful rhythms already have inspired me to explore his remarkable story of courage and resistance, and to kick up my heels, as much as arthritis allows. This production that relies completely on his songs deserves to sell out and to stay for longer than one week. If you want to experience music and theatre at its most inspiring, don’t miss it.

Finally, for an entirely different experience of music and race relations, check out Fela!, a dance-drama depicting the story of Fela Kuti, the Afrobeat pioneer whose life and music is the stuff of legend, in a production that arrived on October 25 and runs till November 6 at the Canon Theatre. Discussing the show, Bill T. Jones, one of America’s most innovative and respected choreographers, says, “One has to experience it as much with one’s hips as one’s ears, eyes and mind.” Given that Jones directed the piece, I could easily accuse him of bias — except that Fela Kuti’s soulful rhythms already have inspired me to explore his remarkable story of courage and resistance, and to kick up my heels, as much as arthritis allows. This production that relies completely on his songs deserves to sell out and to stay for longer than one week. If you want to experience music and theatre at its most inspiring, don’t miss it.

Based in Toronto, Robert Wallace is a retired university professor who writes about theatre and performance. He can be contacted at musictheatre@thewholenote.com.