Here’s a riddle for you. By day they are lawyers, paramedics, marketing mavens, music students, teachers, bus drivers, office managers, dentists and various retirees. By night, they transform themselves into gypsies, peasants, soldiers, courtesans, nuns, prisoners, factory workers, heavenly angels and the demimondaine. Who are they? And the answer is, a typical opera chorus.

That they are indispensible to an opera is a given. “The chorus represents the community or society that the principal characters inhabit,” explains stage director Tom Diamond. And Opera Hamilton chorister Dorothy O’Halloran adds: “We are part of the on-going story. We react to the main characters. In fact, we collectively are a character in the opera.”

That they are indispensible to an opera is a given. “The chorus represents the community or society that the principal characters inhabit,” explains stage director Tom Diamond. And Opera Hamilton chorister Dorothy O’Halloran adds: “We are part of the on-going story. We react to the main characters. In fact, we collectively are a character in the opera.”

David Fallis, music director/conductor for Opera Atelier, describes two kinds of opera choruses. “In early operas like Monteverdi’s Orfeo,’ he says, “the chorus is modelled after a Greek chorus, and comments on the action. They are the observers who interpret the story. They are an extension of the audience. In Verdi operas, on the other hand, the chorus is very emotionally involved with the main characters. They can’t be separated away from the story itself.”

This, then, begs the question — is singing in an opera chorus different from singing in a choir? The answer is apparently yes, although people struggle to explain the “why” of it.

Sandra Horst is chorus master for both the Canadian Opera Company and the University of Toronto Opera Division. Says Horst: “In a chorus, there’s not so much blend of sound as in a choir, which is a single unit of well-trained voices dedicated to purity of singing. An opera chorus has different ages and different kinds of voices. It’s a sound that is together, but where the singers are still individuals. They are not all trying to sound the same. The voices also have to be bigger to be heard above an orchestra and fill a hall.”

Sandra Horst is chorus master for both the Canadian Opera Company and the University of Toronto Opera Division. Says Horst: “In a chorus, there’s not so much blend of sound as in a choir, which is a single unit of well-trained voices dedicated to purity of singing. An opera chorus has different ages and different kinds of voices. It’s a sound that is together, but where the singers are still individuals. They are not all trying to sound the same. The voices also have to be bigger to be heard above an orchestra and fill a hall.”

Opera Hamilton chorus master Peter Oleskevich agrees that there is a huge difference between a choir and an opera chorus. “A static choir, in a fixed position, blends voices together to produce perfection of sound and beauty of unity,” he says. “In an opera, you can’t have the same kind of blend because the chorus is scattered over the stage. It’s a different kind of sound projection. The singing is dramatic. You want the chorus to throw caution to the wind in their music making.” Perhaps OH chorus member Ken Watson, pictured on this issue’s cover, sums up the difference best: “I regard myself as a performer, not just a singer. A chorus member has to act in costume. You have to be comfortable on the stage.”

Opera Hamilton chorus master Peter Oleskevich agrees that there is a huge difference between a choir and an opera chorus. “A static choir, in a fixed position, blends voices together to produce perfection of sound and beauty of unity,” he says. “In an opera, you can’t have the same kind of blend because the chorus is scattered over the stage. It’s a different kind of sound projection. The singing is dramatic. You want the chorus to throw caution to the wind in their music making.” Perhaps OH chorus member Ken Watson, pictured on this issue’s cover, sums up the difference best: “I regard myself as a performer, not just a singer. A chorus member has to act in costume. You have to be comfortable on the stage.”

In order to find those individual voices who can make beautiful music together, opera choruses hold auditions. The COC employs a professional chorus paid at equity rates, but one that is not full-time or tenured. COC chorus members must re-audition every year. The 200 or so hopefuls bring two arias with them, one in Italian, one in another language. Successful singers, most of whom have music degrees, are then offered contracts for each opera. The average size of an opera chorus is 40 people for standard works like Tosca. Mozart operas require only 16 to 20 singers, while Boris Godunov needs 60, Aida clocks in at 65, and War and Peace has a whopping 79. In the final analysis, Horst is looking for quality of voice and the needs of the season’s repertoire. “The acting will take care of itself,” she says.

In order to find those individual voices who can make beautiful music together, opera choruses hold auditions. The COC employs a professional chorus paid at equity rates, but one that is not full-time or tenured. COC chorus members must re-audition every year. The 200 or so hopefuls bring two arias with them, one in Italian, one in another language. Successful singers, most of whom have music degrees, are then offered contracts for each opera. The average size of an opera chorus is 40 people for standard works like Tosca. Mozart operas require only 16 to 20 singers, while Boris Godunov needs 60, Aida clocks in at 65, and War and Peace has a whopping 79. In the final analysis, Horst is looking for quality of voice and the needs of the season’s repertoire. “The acting will take care of itself,” she says.

For Horst’s U of T opera chorus, auditions are open to the music faculty at large. In this case, she’s looking for students who sing beautifully in key. Explains Horst: “You can’t make up a chorus from the opera division alone. There are always many more women, with sopranos being the dominant vocal type. That’s not good if you need four-part harmony. Undergrads can get a credit for being in the opera chorus.” And as a side note, the operas performed by the Glenn Gould Professional School at the Royal Conservatory, don’t, generally, have a chorus. Explains faculty member Peter Tiefenbach: “There are only 30 students so, with such a small student body, we tend to choose operas that feature solo singers.” As a case in point, Cavalli’s La Calisto, just mounted by the school at Koerner Hall, has 14 roles and no chorus.

For Horst’s U of T opera chorus, auditions are open to the music faculty at large. In this case, she’s looking for students who sing beautifully in key. Explains Horst: “You can’t make up a chorus from the opera division alone. There are always many more women, with sopranos being the dominant vocal type. That’s not good if you need four-part harmony. Undergrads can get a credit for being in the opera chorus.” And as a side note, the operas performed by the Glenn Gould Professional School at the Royal Conservatory, don’t, generally, have a chorus. Explains faculty member Peter Tiefenbach: “There are only 30 students so, with such a small student body, we tend to choose operas that feature solo singers.” As a case in point, Cavalli’s La Calisto, just mounted by the school at Koerner Hall, has 14 roles and no chorus.

Opera Hamilton holds yearly auditions to replenish the ranks, but successful candidates do not have to re-audition. The pay is a basic honorarium of $300 to $400 per production, which, as OH general director David Speers quips, is barely enough to cover gas and beer. Oleskevich keeps on hand a roster of around 60 names. He then consults with the stage director. Explains Oleskevich: “I ask him or her how many choristers are needed. Should they be matronly or nubile or both? Do they need to dance? I then send out an email asking who’s available. It’s an amateur chorus, but in the very best sense of the word.”

Opera Hamilton holds yearly auditions to replenish the ranks, but successful candidates do not have to re-audition. The pay is a basic honorarium of $300 to $400 per production, which, as OH general director David Speers quips, is barely enough to cover gas and beer. Oleskevich keeps on hand a roster of around 60 names. He then consults with the stage director. Explains Oleskevich: “I ask him or her how many choristers are needed. Should they be matronly or nubile or both? Do they need to dance? I then send out an email asking who’s available. It’s an amateur chorus, but in the very best sense of the word.”

Guillermo Silva-Marin is artistic director of both Opera in Concert, whose chorus sits on stage with their scores, and Toronto Operetta Theatre, whose chorus is part of the action. About 100 singers show up for his yearly auditions. OinC’s chorus is about 40-members strong. Auditionees bring three pieces in a variety of languages. During the process, chorus master Robert Cooper puts the auditionees through exercises, such as having them repeat various pitches. Cooper is also looking for singers who can perform comprimario roles. While OinC’s auditionees have classical training, TOT hopefuls come mostly from musical theatre backgrounds. Again there is the potential for small soloist roles, and because operetta involves spoken text, auditionees also bring a monologue along with their arias. The average size of the TOT chorus is 16 members. Says Silva-Marin: “Most of our singers are trying to build up stage experience.”

Guillermo Silva-Marin is artistic director of both Opera in Concert, whose chorus sits on stage with their scores, and Toronto Operetta Theatre, whose chorus is part of the action. About 100 singers show up for his yearly auditions. OinC’s chorus is about 40-members strong. Auditionees bring three pieces in a variety of languages. During the process, chorus master Robert Cooper puts the auditionees through exercises, such as having them repeat various pitches. Cooper is also looking for singers who can perform comprimario roles. While OinC’s auditionees have classical training, TOT hopefuls come mostly from musical theatre backgrounds. Again there is the potential for small soloist roles, and because operetta involves spoken text, auditionees also bring a monologue along with their arias. The average size of the TOT chorus is 16 members. Says Silva-Marin: “Most of our singers are trying to build up stage experience.”

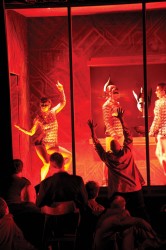

The baroque company Opera Atelier employs both an offstage and onstage chorus, each different from the other. In French opera-ballets by Lully and Rameau, stage director Marshall Pynkoski follows the historical model and places the chorus offstage (in boxes at the Elgin Theatre). Dancers interpret their words on stage. This theatrical convention is also used for the operas of Gluck, Purcell and Handel. The offstage chorus is the highly regarded Tafelmusik Chamber Choir under Ivars Taurins, lauded for their specialized delivery of baroque style, aesthetics and musical language. Nonetheless, as Taurins points out, while they may be off stage, the singers must still memorize the music. “They are visible,” he says. “They are participating in the drama.” Taurins also relates the fact that the pay scale is much lower for a box chorister than for an onstage one. There is a perk, however. The singers actually get to watch the performance.

OA holds auditions for the onstage chorus in the Mozart operas, for example. While it’s not a standing chorus, they do keep a list of people that they ask back who don’t have to re-audition. “We have really rigorous standards in terms of what we’re looking for,” explains Pynkoski. “The company is all about storytelling. The chorus can’t be just a herd of people on stage making a wall of sound. I don’t have time in rehearsals to give acting lessons. The singers have to demonstrate that they can react to character and situations quickly.” Pynkoski and Fallis work together. Once they like the vocal quality of a singer, Pynkoski has to determine his/her movement ability. “It’s important that they understand physical relaxation,” he says, “because that’s the key to comfort on the stage. They also have to be in good shape so they won’t become breathless.”

Pynkoski then sets a “natural” task while the singer is performing an aria. For example, telling them to arrive at a certain chair on such and such a line. Says Pynkoski: “You’d be surprised how impossible it is for some singers to move on cue. The act of singing, the very technique of the art, works against natural physicality.” During the extensive rehearsal period, Pynkoski has actually put iron weights on choristers’ wrists and ankles to force them to relax into gravity, and eliminate tension in the body. In the following, Fallis describes Pynkoski’s process of challenging the auditionees for stage worthiness. “If a soprano is singing Zerlina’s aria “Batti batti o bel Masetto” from Don Giovanni, for example, Marshall asks her to pretend Massetto is actually in the room and that she is singing to him. Or to show that she is frightened of Massetto, or that she is seducing him. If they can pick up these little challenges, they’ll be able to pick up the bigger ones that arise in blocking the stage action.”

The three people who shape a chorister’s life are the chorus master, the conductor and the stage director. Needless to say, music rehearsals are week nights and weekends because every member has a day job. Being in a chorus means a strong commitment to long hours as they follow the tried and true path of music rehearsals, staging rehearsals, piano run-throughs, and finally the piano dress, the orchestra dress, and at last, the performances themselves.

The chorus master prepares the chorus which also includes language work. In fact, learning the music is child’s play in comparison to mastering the words of a foreign language. The scores are available in advance of the first music rehearsal. Members are expected to be off book by the time they are handed over to the stage director. Memorization is the greatest challenge. Oleskevich finds that if he talks about motivation, and deconstructs the music’s architecture, that this deeper understanding helps the chorus come to grips with the composer’s intentions, or as he says, converts the score into “living music.” O’Halloran has her own little memory trick. “I tape just the chorus numbers off a CD, and keep playing it over and over.”

COC chorister Karen Olinyk describes how Horst tries to second-guess what the conductor’s wishes might be. “Sandra has us practise the music in different tempi,” she explains. “We try things both slow and fast, and soft and loud. We have to be flexible to accommodate the conductor.” In fact, so ingrained does the music become in the skin, as it were, that choristers report that when they perform the same opera several years down the line, it is almost instant recall. States Watson: “I know what I’ll be singing on the next page, and I haven’t turned the page yet.” Oleskevich tells the astonishing story of an Otello performance where the curtain failed to open on the storm scene, although the conductor had begun the music. Even though the chorus could not see the conductor, they sang the words without missing a beat.

In the course of my interviews, I learned a new word — sitzprobe. Explains Speers, who will be conducting OH’s upcoming Il Trovatore: “The word literally means ‘seated rehearsal.’ It is the first time that the soloists, chorus and orchestra come together. Everyone is sitting in a chair. The focus is on tempi and dynamics. The purpose is the integration of all the musical forces.”

Which brings us to the thorny question of the stage director. The chorus masters and conductors attend every stage rehearsal. They are there primarily to protect the music. As Olinyk says: “Sandra and the conductor save us from the directors.” Negotiation is the key. For example, the staging has to allow the chorus to see the conductor at all time. They have to get on and off the stage as the music permits. Adds Speers: “The further away from the conductor, the more problems there will be. Even with today’s technology that includes monitors and closed circuit television, a director has to be careful in placing the chorus.”

Directors, it seems, tend to put acting first, but in reality, musical concerns have the final override. Says Oleskevich: “I can remember one director who created such complicated patterns for the male chorus in a Trovatore that the men kept bumping into each other with their spears. The stage manager had to step in to redo it.” And then there are the irritating so-called traffic cops who just tell the chorus to move here and go there. What really upsets most choristers, however, are the directors who are clearly unprepared. “Bring a good book,” declares Watson, “because it’s going to be a long wait while they figure out what they’re doing.”

Choristers, in fact, are willing, even eager, to partake of any stage business, within reason, that a director wants to put on stage. There are, however, strict rules concerning safety issues. With a seasoned chorus like the COC, smart directors allow the choristers to guide them. Explains chorister John Kriter: “We’re good at what we do. We can supply character. If they give us an outline of who we are, we’ll figure out our own story. We also know who we’re comfortable with doing love scenes or fight scenes. We’ve developed these relationships over the years, which makes it easier for directors to use us in the blocking.”

Diamond is a veteran stage director. Over the years, he’s worked out a successful modus operandi when it comes to opera choruses. “The first time I meet the chorus,” he says, “I talk about the opera, and where they fit in. I give character and intention which gives them ownership. I learn their names which builds a closer relationship with them. I pay attention to everyone, and not just the principal singers.” Diamond describes a Manon Lescaut for Pacific Opera which he set in Vichy France. “The town had been bombed by the Allies and everyone in the chorus had a job to do. Some were the clean-up crews. Others were patrons and workers at a café. I had each person figure out what their purpose was on stage, as well as their life story.”

And a final question. What draws singers to audition for an opera chorus? An absolute given is that they like to sing, dress up and be onstage. The choristers mention the enthralling music they get to perform, and the thrill of interacting with the glorious voices of opera stars (who may be, as O’Halloran drolly says, either on their way up or their way down). There are also harrowing stories of quick changes in hallways, and misplaced objects on the prop table. For women, the greatest problem seems to be trains on Edwardian ball gowns, particularly finding the wrist band that raises the train. Big hats are also cumbersome. For men, there is the 40 pounds of weight they carry when a heavy leather soldier’s costume has to fit over a thick wool peasant’s costume because they don’t have time to change between scenes. Women in nuns’ costumes have trouble hearing the music. Ditto for soldiers in helmets.

Overall, however, being in a chorus is a marvellous adventure. “I’m a former teacher,” says O’Halloran, “and when I’d go into the staff room the day after a chorus rehearsal, and look at my colleagues, I’d say to myself, they don’t have a clue about the wonderful life I’m leading.”

Paula Citron is a Toronto-based arts journalist. Her areas of special interest are dance, theatre, opera and arts commentary.