It’s a Saturday night in August, and violinist Geoff Nuttall is on the phone from San Francisco. He’s just flown in from somewhere, and he’s jet-lagged – but not too tired to talk about the St. Lawrence String Quartet.

“We want to connect to the simple idea that music can be powerful,” he says, articulating the artistic vision of the ensemble. “Our goal is to try to make people gasp at the right moment, and feel sad at that right time. That’s a basic concept, but it keeps us going. We don’t want people to go away and say, ‘They were really in tune.’ That’s the kiss of death. We want people to talk about how the music made them feel.”

“We want to connect to the simple idea that music can be powerful,” he says, articulating the artistic vision of the ensemble. “Our goal is to try to make people gasp at the right moment, and feel sad at that right time. That’s a basic concept, but it keeps us going. We don’t want people to go away and say, ‘They were really in tune.’ That’s the kiss of death. We want people to talk about how the music made them feel.”

The St. Lawrence Quartet turns 21 this year – a “coming of age,” if you will. There have been a couple of personnel changes along the way (more on that later), and a few changes of location: from Toronto to New York, and finally to Stanford University, in California. And although the quartet is one of those groups that seems to have been blessed with a meteoric rise, from Nuttall’s perspective it’s been a long, slow struggle to get to where the St. Lawrences are now.

“In a string quartet, you only start to hit your stride after 10 or 15 years,” he says. For instance, we played the Mozart G Minor Quartet last week. I remember playing that in the old days, and working on it for hundreds of hours. But now, with one-tenth of the practice time, it was much better. You get to a comfort level with things like intonation, and accomplish a lot in a shorter time. It allows for freedom to make music.”

That said, the quartet’s meteoric rise makes for a darn good story. It all began back in 1989 when two students at the U of T’s Faculty of Music and two students at the Royal Conservatory of Music got together to form a string quartet.

That said, the quartet’s meteoric rise makes for a darn good story. It all began back in 1989 when two students at the U of T’s Faculty of Music and two students at the Royal Conservatory of Music got together to form a string quartet.

“Early on, there was a lot of luck,” says Nuttall. “It was one of the few times the Conservatory and the University ever got together and collaborated. Everything kept falling into our laps: we studied with the Emerson Quartet, and then we worked with the Juilliard and Tokyo quartets. After three years we’d worked with three of the best quartets on the planet. Without all of that, we probably would have died 15 years ago.”

Modesty aside, Nuttall is probably right when he attributes the quartet’s early successes to good fortune: they were, in retrospect, in the right place at the right time. The Orford Quartet, Toronto’s reigning quartet, was near the end of its long and illustrious career (the group played its last concert in 1991). The St. Lawrences appeared on the Toronto scene just as the city found itself without a professional string quartet. John Brottman, music officer of the Ontario Arts Council, helped out with funding the new quartet – even though he expressed doubts that the group would last more than six months.

Then, in 1992, Jennifer Taylor, artistic producer of Music Toronto, booked the new quartet for not one but two concerts on the city’s flagship chamber series. Neither were exclusive engagements, however: on one concert the quartet played with pianist Robert Silverman; on the other they took to the stage with the Tokyo Quartet. Toronto discovered that it had a new quartet it could call its own.

Later that year, the St. Lawrence Quartet won the Banff International String Quartet Competition – and things started to happen quickly for the SLSQ. “We played in France every year for 10 years after that, solely because of Banff,” recalls Nuttall. “And it was great because it meant that we wouldn’t have to do another competition again!” (Nuttall doesn’t much like competitions, and his experiences both as a competitor and as a juror have done little to alter his opinion.)

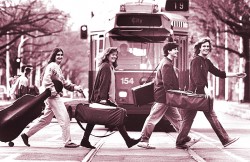

The original St. Lawrence Quartet consisted of violinists Nuttall and Barry Shiffman, violist Lesley Robertson, and cellist Marina Hoover. They were bursting with youthful energy: The Globe and Mail called the group “gutsy”; and a New York Times critic, reviewing the quartet’s debut in the Big Apple, remarked, “I have never heard anything quite like it. In the future, this quartet should make its presence felt.”

Chalk one up for the New York Times. After two decades, the St. Lawrence Quartet has played almost 2,000 concerts around the world: from Toronto to Tel Aviv, and from the White House to a women’s prison in Anchorage, Alaska. What’s the best hall the quartet has played in? Nuttall has fond memories of the quartet’s concerts in the Kleine Zaal of Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw: an intimate 300-seat room up above the main concert hall. But he emphasizes that, for him, it’s not the place, but the music, that’s important.

And the musicians are important, too. One of the fringe benefits of quartet playing is the opportunity to work with other performers on repertoire that goes beyond two violins, a viola and a cello. The St. Lawrences have performed with pianists Menahem Pressler and Claude Franck, soprano Dawn Upshaw, baritone Russell Braun – the list goes on.

After two decades, the quartet now has a discography of eight recordings, featuring everything from Bach to the contemporary Argentinian composer Osvaldo Golijov. The diversity of their repertoire says something noteworthy about the St. Lawrences: the quartet has pointedly not specialized in a particular composer or era.

“I think pigeonholing yourself is dumb,” states Nuttall with conviction. “It means you’re limited in some way. I’ve always been proud of our eclecticism. To play Bartók after Haydn is hard, and not all quartets do it well, but it makes for a better concert experience. The vastness of the repertoire is what makes the string quartet remarkable – so why not do it all?”

Rather, what the quartet has successfully done to carve out a niche for itself is to adopt a unique style of performance. The SLSQ’s vivid style of playing has sometimes drawn criticism as a little too “over the top.” (I myself once likened a St. Lawrence concert to a room lit with ultraviolet light, where all colours were intensified.) But nobody would deny it’s a style that’s all their own.

“They have their own signature,” says Jennifer Taylor. “You always know it’s them. Music Toronto used to present one concert a year at the Lula Lounge, and the very first year, the St. Lawrences played a Bartók quartet. There was a capacity audience – and from the very first note they got total silence, until the applause at the end.”

Taylor is clearly a fan: she’s booked the St. Lawrences every season since their 1992 debut (between 1995 and 1998 the quartet was designated Music Toronto’s ensemble-in-residence). Indeed, the quartet’s annual appearances with Music Toronto – as well as other things, such as masterclasses for students at the University of Toronto – have helped the group retain a certain “home town advantage,” even though they haven’t lived in Toronto for many years.

“They always draw a good, enthusiastic house,” notes Taylor. “Audiences are interested in who’s going to play first violin. And people always like to see how long Geoff’s hair is, and whether Lesley’s wearing glitter or not. We like to think of them, in a sense, as ‘our’ quartet. It’s almost a parental attitude.”

Personnel changes have done surprisingly little to change the quartet’s performance style. In 2002 Hoover left the ensemble, followed by Shiffman in 2006. However, their replacements – cellist Christopher Costanza and violinist Scott St. John, respectively – have fit in well.

“I think it’s made us better,” suggests Nuttall. “If you get the right person, it brings a new energy. Both Scott and Chris could have a major solo career, and you can’t say that about too many quartet players. Chris and Scott don’t play out of tune – it just doesn’t happen. They’re out of my league!” However, he’s also quick to point out that the current quartet has maintained close relationships with its former members, and has given “reunion” concerts, with all six musicians on stage.

Last year was the St. Lawrence Quartet’s 20th anniversary, which in Nuttall’s words, was “a good excuse to do some interesting stuff.” And indeed they did. One of the ensemble’s anniversary projects was the premiere of John Adams’ String Quartet. But the St. Lawrences didn’t ask the famous American composer to write the piece for them – he approached them. “He came to hear a performance we gave,” Costanza explained in an interview with the Detroit Free Press. “He came backstage afterward and said, ‘The Beethoven Op. 132 was great. Could I write a quartet for you guys?’”

And true to the group’s Canadian roots, they took advantage of their anniversary year to commission not one but five new quartets from Canadian composers: one from the West Coast, one from the Prairies, one from Ontario, one from Quebec and one from the Maritimes. The selected composer were (from west to east) Marcus Goddard, Elizabeth Raum, Brian Current, Suzanne Hébert-Tremblay and Derek Charke.

With their anniversary year now behind them, the quartet shows no sign of resting on its laurels. Their first engagement in Ontario in the 2010-11 season will take them to Owen Sound’s Sweetwater Music Weekend, for two concerts, on September 17 and 19.

After that, they return to Toronto in October to open Music Toronto’s season, on October 14. They’ll play Haydn’s Quartet Op. 74 No. 1, Prokofiev’s Quartet No. 2, and a pair of their recently commissioned Canadian works: Hébert-Tremblay’s À tire-d’aile (2009), and Goddard’s Alliqi. The following day, they’ll perform for the Ottawa Chamber Music Society. And in the new year, the quartet will be back in Toronto for a concert at the U of T Faculty of Music on February 28.

Still, after 20 years on the road, Nuttall hints that life in a busy string quartet can grow wearisome. “We do crazy things, like getting up at three o’clock in the morning to go to the airport,” he says. “Someday, we’d like to have a perfect hall somewhere, and play 120 concerts a year in it – and people would come to us!”

Colin Eatock is a composer, writer, and the managing editor of The WholeNote.