I had heard through the musician grapevine that baritone Brett Polegato owns a remarkable library, but putting in a request to poke around someone’s house and then write about it is not the easiest of asks. This March, however, after a sudden flurry of cancellations of his Lebanese, Italian and Nova Scotian engagements due to You-Know-What, Polegato found himself spending an unusual amount of time at home and we easily scheduled a get-together. I visited the three-storey row house he shares – or shall we call it his three-storey library – in the Carlton and Church area on one of the last evenings before the city went into a complete lockdown. Like a majority of working artists, he’s been hit hard by the loss of income due to cancellations. But this evening we decide to focus on what brings joy.

I had heard through the musician grapevine that baritone Brett Polegato owns a remarkable library, but putting in a request to poke around someone’s house and then write about it is not the easiest of asks. This March, however, after a sudden flurry of cancellations of his Lebanese, Italian and Nova Scotian engagements due to You-Know-What, Polegato found himself spending an unusual amount of time at home and we easily scheduled a get-together. I visited the three-storey row house he shares – or shall we call it his three-storey library – in the Carlton and Church area on one of the last evenings before the city went into a complete lockdown. Like a majority of working artists, he’s been hit hard by the loss of income due to cancellations. But this evening we decide to focus on what brings joy.

We skip the ground floor, which houses the piano, the CD collection in the middle of a major clearing out, and the downstairs books to which we’ll return, and go up to the living room. There are already bookcases here, behind glass doors in cubes on each side of the sofa, and I spot Naomi Alderman’s Disobedience in one of those. But that’s just a teaser for the main event upstairs, with the first stop in what looks like a linen closet. Packed with books.

“This is probably one of the oldest signed books that I have.” He pulls out a vintage edition of Philip Pullman’s Galatea (1978), which the author refused to re-issue in his later life. I spot an entire section of Ian McEwan and David Mitchell. “I have everything that Ian McEwan ever wrote,” says Polegato; his favourite is an early McEwan, The Child in Time. Where to start with David Mitchell, those of us who haven’t? “I’m a fan. Probably Cloud Atlas. His other two books are interlinked short stories with characters that appear in Cloud Atlas.” There’s some Peter Carey in the closet too; I spot Sarah Perry’s Gothic Melmoth, a Tom McCarthy volume, and …David Duchovny?! “Holy Cow is a novel – The X-Files star actually writes novels,” he says when I raise an eyebrow. But then I notice Aleksandar Hemon when another door opens. “I have all of Aleksandar Hemon, and probably all of the André Aciman now.”

We leave the hallway and move on to the room that functions primarily as a library, with bookcases covering every wall. The books here are sizable, and are stunning objects to look at – not regular hard covers but bibliophile editions. A large section of Robertson Davies – “I got this book that he signed and dedicated to painter Max Bates in Victoria, I must have been 23 when I bought it” – and a lot of shelf space for Philip Pullman. “I wanted all the Philip Pullman books signed. This is His Dark Materials – these are all North American editions, but I also wanted British editions which cost ridiculous kind of money.” He only buys books in hard cover now. “It started with Pullman, and it spiralled out of control,” he says. “There is all of Michael Cunningham here too.”

Next we move to two cases which house classics in the most beautiful editions available. “These are all Folio edition books,” he says. “I joined the Folio [Society] years ago, when you had to buy four books per year to be a member. What I liked about them is that they were publishing in hard covers what you never find republished anymore.” My eyes are drawn to a luxurious complete Henry James and a towering single-volume Brothers Karamazov. “There’s Virgil’s The Aeneid, the Homer… all the way to the Chronicles of Narnia, all of the Dante…” He pulls out Dante’s Divine Comedy: “These Folio books are all hand-sewn; wherever you open them, they lie flat.” Moving on: “This is all of Charles Dickens. All of Thomas Hardy and Jane Austen in hard cover. Those are Mapp and Lucia… that’s E.M. Forster.” I spot a stunning complete hard cover set of In Search of Lost Time, which he also has, it’ll turn out later, in a hand-friendly quality paperback downstairs on the ground floor shelves. He has yet to read Proust – I urge him to, as he’s one of my favourites – but like a lot of book lovers who read a lot, he collects even more than he can catch up with and enjoys that state. What motivates him to collect? “My goal was that some day when I’m retired and have a big library, I could just walk up to the shelves and say, ‘Hmm what do I want to read today?’ And have practically everything, Paradise Lost, or Wings of the Dove, or Roald Dahl complete tales.”

And when a global pandemic strikes and puts a pause on everything, what better refuge than a library so well stocked?

How does he decide what to buy? “One of the writers that I love, the Australian Steve Toltz, has a character in A Fraction of the Whole say: ‘All great books are about other books.’ I think that’s true. Often when you read, somebody will mention a book in conversation, or the dust jacket will say this is like X, Y or Z. For example, when I read The Beach by Alex Garland, which was made into a movie with Leonardo Di Caprio, the blurb described it as a combination of Lord of the Flies and The Magus by John Fowles. So after that I read The Magus; and while that was happening, somebody said to me OMG you have to read Fowles’ The Collector, so I read that. I think the same thing happens with movies.”

“My goal was that some day when I’m retired and have a big library, I could just walk up to the shelves and say, ‘Hmm what do I want to read today?”

By now we’ve crossed to the large video collection on the other side of the room –another two standalone cases. Many TV series on BluRay, and a place of prominence for Dr Who, and Martin McDonough’s film In Bruges. And also … The Seven Year Itch with Marilyn Monroe? “There was a deal on Amazon for nine Marilyn Monroe films and I got all of them, … Niagara, Some Like it Hot, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. One of the films had Montgomery Clift, and so I started buying Montgomery Clift films. I was re-watching Sunset Boulevard and that same year that Gloria Swanson was nominated for an Oscar, Judy Holiday won it for Born Yesterday. So I looked for it and it’s now one of my favourites. Then I started buying Judy Holiday films.”

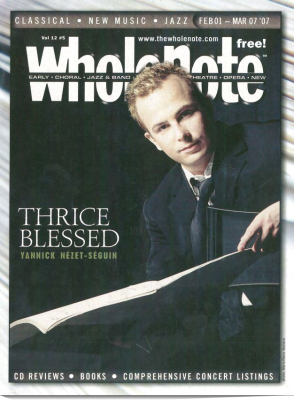

Are there actors, directors whose aesthetic he prefers or is influenced by? “I’m into… economical actors. I wouldn’t say Bette Davis is subtle but she’s economical in the way she uses gestures and looks. I don’t find her hysterical … even when she’s over the top, she’s efficient.” The stars of old Hollywood had greater presence, and were certainly not chameleonic, the way some of the method actors of today are. Is the old school closer to his tastes? “Hmm… This is what I liked when working with Yannick Nézet-Séguin – and the first thing I did with him was here in Toronto, a Faust production when the Four Seasons Centre opened as the new home for the COC. Yannick really allows the artist to inhabit things in their own style. He provides a comfortable environment for you to shine. I think that’s true for a lot of old directors and conductors, people like James Levine … you could see that they helped singers. It feels that in contemporary art-making there’s much more control asserted by the director, more direction placed on the artist.”

But should we be nostalgic for an era of megastars who, while they sold a lot of tickets, never particularly bothered to act? Is it bad that we now expect even divos and divas to act – and for opera to be a full theatrical experience? “No, I agree. As an actor I’ve worked with Pierre Audi, with Robert Wilson, James Robinson, Kelly Robinson … Some have a more realistic approach, some are funnier, some are more surreal. I’m used to all of those styles; it gives me a greater adaptability when it comes to working with a new director.”

But should we be nostalgic for an era of megastars who, while they sold a lot of tickets, never particularly bothered to act? Is it bad that we now expect even divos and divas to act – and for opera to be a full theatrical experience? “No, I agree. As an actor I’ve worked with Pierre Audi, with Robert Wilson, James Robinson, Kelly Robinson … Some have a more realistic approach, some are funnier, some are more surreal. I’m used to all of those styles; it gives me a greater adaptability when it comes to working with a new director.”

Other actors he appreciates are Daniel Day-Lewis (speak of “chameleonic!”), Colin Firth, Julianne Moore (“she’s incredible”). “I love Gene Kelly and admire his ability to be so elegant and masculine at the same time.” As for directors, a recent big revelation has been Paolo Sorrentino. “Because I was in Rome recently, a friend told me I had to watch La grande bellezza [The Great Beauty] and watched it now twice, it’s staggering. That’s the reason I bought La notte and L’avventura. Sometimes I just respond to visceral cinematic imagery… like Julie Taymor’s Titus Andronicus, Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon. With some films you sometimes think, I don’t know what that is, but it moves me.”

We linger some more in the Folio room while I ask him about poetry. “As I’m getting older, I respond a lot to poetry. I was never a big poetry buff growing up. But Gerard Manley Hopkins has become essential for me – it’s the images that bypass intellect. Cinema does the same thing, sometimes you just see the picture and the emotion registers before the intellect grabs on to it. Same thing with acting. I like directors who pull that out of me. Who stop me from intellectualizing the process.” He goes to theatre a lot, in his home town and whenever abroad, much more than to opera. “I always watch the actors who are not speaking. I want to see how people live on stage. It’s far easier to have the floor.” Is he more a Soulpepper kind of person or the Matthew Jocelyn’s Canadian Stage kind of person? “Maybe a little more Soulpepper. I like to be told a story but it doesn’t have to be in a linear, traditional fashion. It can be Ivo van Hove staging The Damned with video projections, which I saw at the Barbican in London.”

Is he like that as a reader too? Let’s keep the structure of the storytelling and don’t mess too much with it? “David Mitchell for example isn’t traditional storytelling at all,” he says. “And I have to mention Gerard Manley Hopkins again, whom I read over and over … and Thomas Hardy. Edna St. Vincent Millay.”

We have moved to another room, which has its own library and a mountain of books on the floor: the “To-Be-Read” room. I spot Alan Hollinghurst – Polegato’s partial to The Stranger’s Child, a historical novel on literary memory built around a fictional English poet resembling Rupert Brooke. “Kevin Barry! Now there’s an author that I love. Have you read City of Bohane? That’s a good example of the kind of stuff that I like. A bit like James Joyce. Dubliners is one of my favourite books ever.” I notice with delight that he has purchased all three Eimear McBride novels – another Irish writer working in Joycean, modernist tradition – and placed them prominently on their own. Oh and look, I say, there are the Ali Smith’s fast zeitgeist novels, Autumn, Winter and Spring – but he’s moved on to the poetry pile, bringing out Philip Larkin, Billy Collins, John Ashbury. “I’m very eclectic. This woman for example, Frances Hardinge, writes amazing YA fiction. The way she writes is so alive, so unpredictable.” There is a lot of CanLit on his shelves too. “I love Colin McAdam. There are things by Atwood that I like, but I like Lisa Moore even more. A friend of mine, Gil Adamson, is about to publish a new book. I love Joseph Boyden, Lynn Coady … I loved Anne Michaels before the world caught on.”

We have moved to another room, which has its own library and a mountain of books on the floor: the “To-Be-Read” room. I spot Alan Hollinghurst – Polegato’s partial to The Stranger’s Child, a historical novel on literary memory built around a fictional English poet resembling Rupert Brooke. “Kevin Barry! Now there’s an author that I love. Have you read City of Bohane? That’s a good example of the kind of stuff that I like. A bit like James Joyce. Dubliners is one of my favourite books ever.” I notice with delight that he has purchased all three Eimear McBride novels – another Irish writer working in Joycean, modernist tradition – and placed them prominently on their own. Oh and look, I say, there are the Ali Smith’s fast zeitgeist novels, Autumn, Winter and Spring – but he’s moved on to the poetry pile, bringing out Philip Larkin, Billy Collins, John Ashbury. “I’m very eclectic. This woman for example, Frances Hardinge, writes amazing YA fiction. The way she writes is so alive, so unpredictable.” There is a lot of CanLit on his shelves too. “I love Colin McAdam. There are things by Atwood that I like, but I like Lisa Moore even more. A friend of mine, Gil Adamson, is about to publish a new book. I love Joseph Boyden, Lynn Coady … I loved Anne Michaels before the world caught on.”

I ask him about Kazuo Ishiguro, whose books I spot on the lower shelf before we head down the stairs. “Huge Ishiguro fan, especially Never Let Me Go. Richard Powers. Michel Faber. All wonderful.” Is there anything that you never buy and never look for? “I read very little crime fiction,” he says. You don’t need a book to be plot-y? “Not at all. Take for example Dan Chaon, You Remind Me of Me. I cannot tell you the number of people who’ve read it and tell me nothing happened. I tell them, ‘What do you mean nothing happens, you learn all about these people!’ I am more interested in discovering people; while I appreciate storytelling, I don’t need to be told a story the Dan Brown way.”

Before we part ways, I ask him about projects coming up after this season of cancellations is over, if by then it is. A Canadian Art Song Project recording is on the agenda for May, and on June 6 a concert in honour of Randolph Peters’ 60th birthday, with music by John Estacio, Vincent Ho, Bramwell Tovey and Peters himself. On June 14, Off-Centre Music Salon and Petersburg, a song cycle by Georg Sviridov. In the fall, no small feat: the title role in Rossini’s Guillaume Tell with Irish National Opera.

But meantime, at home, the comfort of books – the more books, the better.

Lydia Perović is an arts journalist in Toronto. Send her your art-of-song news to artofsong@thewholenote.com.