Marc-André Hamelin sometimes thinks that music should have its own semantics. “Deep down I would like the public to be affected by music and respond to music as they would respond to something which has a narrative structure and a message to deliver,” he told me in a February 10, 2017 phone conversation. “And I’ve always said that a performer should be able to express almost any adjective in the dictionary through their playing. Even though it’s kind of a fantasy, it’s a nice goal, a good aspiration.”

Marc-André Hamelin sometimes thinks that music should have its own semantics. “Deep down I would like the public to be affected by music and respond to music as they would respond to something which has a narrative structure and a message to deliver,” he told me in a February 10, 2017 phone conversation. “And I’ve always said that a performer should be able to express almost any adjective in the dictionary through their playing. Even though it’s kind of a fantasy, it’s a nice goal, a good aspiration.”

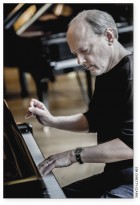

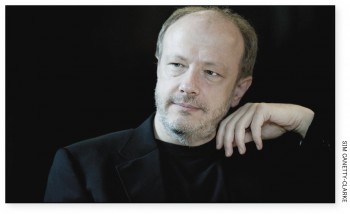

We were chatting in advance of Hamelin’s appearance March 23 in a recital presented by Music Toronto. The occasion was a follow-up to my profile of the master pianist that appeared in the December 2015 WholeNote. Hamelin was his usual affable, thoughtful and convivial self. We spoke about his ambitious all-sonata program for the concert – a late Haydn, the first two sonatas by the little-known Russian pianist-composer Samuel Feinberg, Beethoven’s Appassionata, Scriabin’s White Mass and Chopin’s Second which is built around a funeral march.

Hamelin was describing his connection to the Chopin sonata on the program, which he had recorded for Hyperion in 2008, prompting my question about how his relationship with that particular work has evolved over the years. “You know, it’s something that I’ve known literally all my life,” he said. “We’ve talked about this before I’m sure. Because of my dad, listening to these things all the time, recordings were playing all around the house. I think he probably played it a little bit himself although it’s a very difficult piece. It’s been in my ear since I was a boy so I came to it already sort of knowing it. I didn’t have to explore the score to find out about it. I already knew it. Although when I started to play it of course, there were many things that the score revealed to me that had not been apparent to me when I heard the piece through recordings.”

Indeed the importance of his father to Hamelin’s musical aesthetic and his reputation, right from the start, as an ambassador for late 19th and early-20th-century pianist-composers, many of whom had been formerly unfamiliar to a wider audience, was a key component of my earlier article.

“But as far as the evolution [of his relationship to the Chopin sonata], my God, what to tell you, I don’t know. I’ve always considered it one of the towering masterpieces of the repertoire, one which curiously enough I think is open to a variety of views, a variety of different interpretations, a variety of ways of expressing it. But it’s always appeared to me, perhaps even more now, as one of the darkest and most disturbing statements ever written for the piano.”

I asked for an elaboration.

“Well, you know Schumann’s quote saying that Chopin put four of his maddest children under one umbrella and published this sonata. The four movements are – if you consider the [third movement] Funeral March the heart of it – you could perhaps consider the first two movements as sort of working towards the funeral march and the fourth being sort of an illustration, an afterthought or a consequence of it, as much of a dark mood as the third movement but also expressed completely differently with different means.

“It’s very hard to talk about because it’s something that I’ve known for so long that it’s hard to take some steps back,” he said, laughing.

When he plays it, he said, it’s like he’s reciting a poem. A case in point in terms of his aspirational fantasy: “a narrative structure and a message to deliver.”

Our conversation soon turned the topic of the importance of the score in his pianistic approach. (“The score is still my ideal,” he had told me back in the fall of 2015.) This time, we were discussing Samuel Feinberg as pianist. (“Give a listen to his Well-Tempered Clavier,” he said. “It’s the best that’s ever been produced. It was reissued on CD at least three times and I’m sure you can hear all of it on YouTube if you look hard enough.”) I then commented on Feinberg’s playing of the Appassionata, and then asked what Hamelin’s approach was. He paused before saying with a slight sigh that he plays it and he’s probed it but that his main thrust has been to discount and ignore all outside influences including performing tradition and recordings.

“My arbiter, my one guiding spirit is always and will always remain, the score,” Hamelin said. “Because, especially when I tackle repertoire that everyone knows, I want a fresh perspective. And being a composer yourself gets you to appreciate a lot more the letter itself and what the composer directly tries to communicate. And that kind of thing, the act of communication of your intentions as a composer is a very arduous process and you never know if you’re going to be understood or not. And of course you have to worry about your intentions being disregarded as often happens, because sometimes performers think they know better,” he laughed generously. “I’ve been guilty of that a few times myself. But composing really teaches you respect of the score and that’s where I go to first and foremost.”

When I pointed out that sometimes it takes years or generations for composers to be understood he mentioned Feinberg as an example of someone who will never be a household name or really enter the standard repertoire but that doesn’t mean that one shouldn’t hear him. In fact, Hamelin has a long-term project to remedy the shortage of recordings of Feinberg’s work. “Right now I’m concentrating on the first six sonatas which are a fascinating corpus,” he said. “I’ve already played the first two quite a number of times. And people have actually responded to them with great delight. Which I’m happy to hear.”

Hamelin is playing those sonatas in Toronto in March. I asked when he first discovered the composer’s music. “Oh, I’ve had his scores since the 80s,” he said. “When you’re interested in out-of-the-way repertoire as I’ve always been, his name inevitably comes up. The problem was at the time, indeed for the entire 20th century, scores had been impossible to get in the West, so we just didn’t know what the music looked like. The only two things that were published in the West as far as I’m aware were his Sixth Sonata and a set of preludes. And that was because Universal Edition in Vienna put them out. And I think they’re still available. But he wrote 12 sonatas and a host of other pieces – three piano concerti, a violin sonata and some songs.

“Now it’s almost all available through IMSLP so it’s not a problem,” he said. “But what is also a stumbling block perhaps for anybody who’s taken the trouble to look at the music, is his style itself which is really very complex and very, very chromatic. In a way, in a certain sense, it could be said that he takes his point of departure from Scriabin, but aside from a couple of early works – and the two sonatas that you’ll be hearing me playing fall into that category – you do hear some Scriabin influence. But after that, trust me, he sounds like no one else but Feinberg, because he really developed his own aesthetic.”

Bringing the conversation back to the Appassionata I pointed out how remarkable it is that Beethoven wrote the Eroica Symphony, the Triple Concerto and the Appassionata all in the same year (1805). And then spent the next two years writing the Razumovsky Quartets and the Fourth Piano Concerto.

“It’s mind-boggling,” Hamelin said. “The creativity. The inspiration just kept coming.”

The 55-year-old Hamelin’s March 23 Jane Mallett concert is his 12th solo recital for Music Toronto going back to 1986, a time when “I was still in my infancy as a musician and of course we’re always evolving. Of course I could only give what I had. Sometimes I wish I could go back and do it again [he laughed heartily].” He remembers that first recital very clearly. His father was still alive then [He died in November of 1995.] and made the trip from Montreal to hear him. “I think I gave Balakirev’s Islamey as an encore or it might have been part of the program. I’m not sure. Back then I was a different pianist and I played very different things,” he said, laughing again. “It was very possibly one of the first of my concerts in Toronto, if not the actual first.”

I asked about his association with Music Toronto. “Their heart’s in the right place,” he said. “They’ve been wonderfully faithful to me and I’ve never taken this lightly. My God, we’d be silly not to go back to places that welcome us always with open arms. And where audiences seem to trust you and accept you and welcome you as a regular. It’s such a wonderful thing and it’s the best thing for us musicians really.” He finds the Music Toronto audience to be “music lovers through and through.”

I wondered if he has noticed a change in audiences over the years but he said “No, not really.” He continued: “I think the enthusiasm is always there, it’s just that different audiences have different ways of expressing it. I have an interesting story of a piano festival I played in once in Italy, in the town of Brescia. Which is a pretty important piano festival there. Brescia and Bergamo, they’re pretty close together. I played my first half and the applause was generally lukewarm. I go offstage at the end of the first half and the applause was just enough to get me backstage. And then I wasn’t able to come out again to bow so I thought, ‘Okay, I’ve blown it somehow. So I sort of played the second half with my tail between my legs, at least psychologically. I was really perplexed and disappointed of course [when the response after the second half was the same], but talking to the people afterwards I found out that contrary to my expectations they really, really enjoyed the recital. They just had a way of expressing it which was anything but overt. Since then I’ve learned to give audiences the benefit of the doubt because of that.”

Hamelin’s Toronto concert opens with the two-movement Haydn Sonata in C Major Hob. XVI:48. He told me that the first movement is in a slow tempo and is one of the many examples Haydn produced of a set of double variations, where two themes are presented and varied alternatively. “Then we have a very jolly, typically roguish kind of rondo for the second movement. Full of wonderful humour.”

After intermission he’ll be playing Scriabin’s Seventh Sonata “White Mass,” a piece he recorded for Hyperion in 1995. He told me that his thinking on the piece – the one Scriabin sonata he plays the most – hasn’t changed since that recording was made. “Perhaps I’m able to express it [his thoughts on the piece] a little bit better because of my ongoing relationship with the instrument but otherwise I’d be very hard put to pinpoint exactly what it is I do differently,” he said. “I do have a recording of my very first performance of it which is back in 1983. It would be interesting to listen to that. I haven’t for quite a while.”

Does he listen to his older recordings very often? “Sometimes. I don’t make a habit of it. Every so often I’m curious. It’s hard to get me to listen to anything that I’ve done but once I’m in – I mean, it’s like me in a pool – it’s hard to go to the pool but once I’m in it’s hard to get me out.”

Characteristically, when I asked whether his approach to the piece takes Scriabin’s voluminous writings into consideration or is it mainly confined to the score, he said: “I think he expresses enough in the music itself that he gives you almost more than you can do at a piano given that some of the expressive indications are so outlandish. You don’t have to read, for example the Poem of Ecstasy or know about what he did later about the Ethereum…. The score again should be more than enough of an inspiration.”

Several days before we spoke, Hamelin performed the world premiere of his Piano Quintet with the Pacifica Quartet in California on February 2. Where did he find the time to compose given his busy schedule?

“Well the piano quintet was a long time in the making. First of all, I had written, back in 2002, a Passacaglia for Piano Quintet that was a commission for the Scotia Festival of Music and it was performed at that time. About a year and a half ago I got this commission from California to expand the work into a full [three-movement] piano quintet using this passacaglia. So it got started in 2002. Meantime back in 2005 I wrote an exposition to the first movement. And all of the rest, the rest of the first movement and the third movement were more recent. So I had plenty of time [laughs]. But also, at the same time that I finished this quintet I was also fulfilling a commission to write the compulsory piece for the next Van Cliburn Competition.”

As well as writing that piece, Hamelin will serve on the Cliburn jury. He added that the competition will be live streamed so people won’t have to travel to Fort Worth. “And get this! This time everybody is playing the piece, not just the semi-finalists or whatnot. So the public and jury and worldwide audiences alike will have ample opportunity to get sick of it.”

“Well, that’s really something to look forward to,” I said.

“To get sick of it?” he laughed.

“Yes,” I said. “It’s like jumping in the pool as you say.”

“At least the piece isn’t too long,” he said. “They asked me for four to six minutes and it ended up being about five. So it’s sort of a quick and painless injection.”

“How many times will we hear that piece of yours?” I asked.

“At least 30,” he answered. “That’s why I’m saying ‘sick of it.’”

A few days after we spoke, Hamelin set off for Lyon where the program is the same as that in Kingston, Cleveland, Toronto and eventually home to Boston, May 5. He was particularly looking forward, he told me, to his concert February 20 and 21 in Munich with the Medtner Second Piano Concerto – along with the Rachmaninoff Third, his next Hyperion release. It was to be his first time with the Bavarian State Orchestra though not his first time with conductor Kirill Petrenko. “I’ve worked with [him] once already at the Chicago Festival and that was very, very nice,” he said. “And he’s of course heading to the Berlin Philharmonic. That’s a very nice connection. Although I have played with the Philharmonic once back in 2011.” Then the BPO had asked him to play the Szymanowski Fourth Symphony “Symphonie Concertante” which was written for Arthur Rubinstein, and unknown to Hamelin at the time.

After Toronto, his grand tour continues with 13 duo-piano concerts he and Leif Ove Andsnes are playing in Europe and the USA. Plans include a recording for Hyperion of Stravinsky’s Concerto for Two Pianos and The Rite of Spring. But Hamelin’s next recording to be released (in August) is Morton Feldman’s For Bunita Marcus which he performed in Mazzoleni Hall at the 21C Festival in 2014.

His relationship with Andsnes goes back to 2008 when Hamelin was invited to Andsnes’ chamber music festival in Risør, Norway. “We played The Rite of Spring and in many other places, 10 or 12 times total, including at the Berlin Philharmonic in the smaller hall, because he had a residency there.”

As we finished our conversation I asked him about his fondness for record collecting. “Most of it’s in storage,” he said with a hearty laugh. Even so, I asked if he had been adding to it. “Oh sure, I’m always buying things. But one needs less and less and less with advancing age. I still collect for the pleasure of it though. I’m always on the lookout for the rare things.”

You can hear Marc-André Hamelin – that rarest of performers – in his Music Toronto recital on March 23 at the St. Lawrence Centre, or in the same program, four days earlier, on March 19, at The Isabel Bader Centre in Kingston, Ontario.

Paul Ennis is the managing editor of The WholeNote.