From Burdock to the Bistro - Giving Thanks For October

For many, September marks a transitional period: we go back to school, back to work, back to a daily routine that can either feel welcome (structure! responsibility!) or unwelcome (structure! responsibility!), depending on the quality of our summer experiences. Whatever the case may be, the calamities of our collective re-entry into the real world usually resolve themselves by October, giving us all a bit more time to go out and enjoy live music, at venues both familiar and not. In addition to discussing exciting upcoming performances by the legendary jazz singer Sheila Jordan and the Afro-Cuban group OKAN, the focus of my column this month is on Burdock, a relatively new venue that may be a familiar name to some, but which, I suspect, may be unfamiliar to many readers. (In this month’s listings, you’ll find the full monthly schedule for Burdock.)

In a short amount of time – it opened in April of 2015 – Burdock has emerged as one of Toronto’s most important live-music venues. Located on Bloor, just west of Dufferin, Burdock is divided into two parts connected by heavy, soundproof double doors. On one side is the Music Hall, an intimate space that can accommodate about a hundred people, complete with its own bar, seating (depending on the show), and an excellent sound system. (Burdock consistently sounds great, owing, in no small part, to the talents of their live audio engineers, Aleda Deroche, Matthew Bailey and Jess Forrest.) On the other side is the brewpub, with a rotating tap list of beers, brewed in-house, and a full menu of seasonal food, including both small and larger plates, such as their summer tartine, crispy ribs and wild mushroom taco, all on the menu at the time of the writing of this column. As a brewery, Burdock has found a niche in the busy Toronto beer market by focusing on saisons, sours and wine/beer blends, such as their ever-popular BUMO series, brewed in conjunction with the Niagara-based winery Pearl Morissette. This decision has proven fruitful: by avoiding entering into the high-ABV arms race, Burdock’s brewery has found success at their bottle shop, their own bar, and on the beer list at many of Toronto’s best restaurants.

Through the double doors in the Music Hall, venue coordinator Charlotte Cornfield books acts from a variety of different genres. (Cornfield is an accomplished musician in her own right, touring and releasing music regularly under her own name.)

While many of the musicians who play at Burdock come from Toronto’s creative indie scene, Burdock also regularly features jazz and blues, as well as the occasional classical performance, including, in October, an installment of Haus Musik, presented by the Toronto-based Baroque orchestra Tafelmusik. (The concert will feature members of the orchestra and special guest percussionist Graham Hargrove performing music written by Italian composer Luigi Boccherini.) Beyond its regularly scheduled programming – which has recently jumped from one to two shows per day, due to increasing demand – Burdock also hosts a number of special events throughout the year. Their annual Piano Fest, which celebrated its third birthday this past January, is built around the simple premise of temporarily installing a high-quality grand piano on stage and booking piano-centric acts in complementary double bills; this year’s festival featured artists such as Joanna Majoko, Chelsea Bennett, Tim Baker and Jeremy Dutcher, the latter of whom would go on to win the Polaris Prize in September of this year for his debut album Wolastoqiyik Lintuwakonawa.

In addition to Tafelmusik’s show, there are a number of notable performances that will be taking place in October. These include a modern jazz double bill, with AKKU Quintet and Living Fossil, on October 2 (Living Fossil’s debut album NEVER DIE! was reviewed in our March 2018 issue.); a live recording of radio personality Laurie Brown’s Pondercast podcast, with music provided by Joshua Van Tassel, on October 9; jazz bassist Robert Lee’s Big Band, celebrating the release of the EP Blink, on October 14; and francophone singer/songwriter Safia Nolin, fresh off the release of her third album, performing on October 25.

In addition to Tafelmusik’s show, there are a number of notable performances that will be taking place in October. These include a modern jazz double bill, with AKKU Quintet and Living Fossil, on October 2 (Living Fossil’s debut album NEVER DIE! was reviewed in our March 2018 issue.); a live recording of radio personality Laurie Brown’s Pondercast podcast, with music provided by Joshua Van Tassel, on October 9; jazz bassist Robert Lee’s Big Band, celebrating the release of the EP Blink, on October 14; and francophone singer/songwriter Safia Nolin, fresh off the release of her third album, performing on October 25.

It also seems important to note, for those who have not yet visited, that the Burdock Music Hall is an uncommonly comfortable venue that shifts its seating structure around to accommodate the needs of specific acts and their audiences, even when those audiences comprise a variety of different demographic representatives. In a recent show I attended at Burdock, the open area in front of the stage was flanked by a few narrow rows of chairs. While enthusiastic attendees danced, those audience members who desired a bit more comfort – some of whom, let it be said, were quite possibly related to the musicians on stage – sat and enjoyed an unobstructed view of the performance. At no point did this mixed setup feel divisive or contrived; as is typically the case at Burdock, the vibe was relaxed, inclusive, and fun.

Sheila Jordan at the Jazz Bistro

Sheila Jordan at the Jazz Bistro

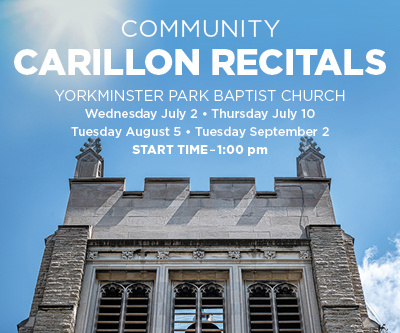

There are a number of excellent shows happening in other venues this month, not the least of which will be Sheila Jordan’s three-night engagement at Jazz Bistro, on October 4, 5 and 6. Jordan, now 89, has a storied history within the jazz community, studying with Lennie Tristano and Charles Mingus in the early 1950s, performing and recording with Herbie Nichols, George Russell and Lee Konitz in the 60s and 70s, and teaching, as artist-in-residence, at City College of New York, from 1978 through to the mid-2000s. Jordan – who was referred to as “the singer with the million dollar ears” by Charlie Parker – will be joined by pianist Adrean Farrugia and bassist Neil Swainson in an intimate trio format, whose instrumentation should prove well-suited to Jazz Bistro’s ecclesiastical acoustics.

OKAN at Lula

At Lula Lounge, OKAN celebrate the release of their debut EP recording on October 21. Co-led by Cuban-born, Toronto-based multi-instrumentalists Elizabeth Rodriguez and Magdelys Savigne – both of whom are veterans of saxophonist/flutist Jane Bunnett’s Maqueque group – OKAN fuses traditional Afro-Cuban music with jazz, pop and soul. In their live show, Rodriguez and Savigne find success both in the complementary chemistry they share as performers (Rodriguez typically stands and plays violin, while Savigne sits behind her congas; both sing.) and in their talent for deftly borrowing from various musical sources. At times OKAN’s music sounds distinctly Afro-Cuban; at other times, like pop-inflected R&B. Anchored by Rodriguez and Savigne, this month’s show should prove to be a worthwhile reason to visit Lula Lounge.

MAINLY CLUBS, MOSTLY JAZZ QUICK PICKS

OCT 4 TO 5, 9PM: Sheila Jordan, Jazz Bistro. Accompanied by local mainstays Adrean Farrugia (piano) and Neil Swainson (bass), legendary jazz singer Sheila Jordan performs in this three-night run at Jazz Bistro.

OCT 14, 9:30PM: Robert Lee, Burdock. Upright bassist Robert Lee leads his big band in celebration of the release of his EP Blink, a collection of modern jazz pieces inspired by pop, folk and classical music.

OCT 25, 9:30PM: Safia Nolin, Burdock. Francophone singer/songwriter Safia Nolin – 2017 Félix Award winner for Female Artist of the Year – performs in support of her new album, releasing October 5.

OCT 21, 6:30PM: OKAN, Lula Lounge. Co-led by Cuban-born multi-instrumentalists Elizabeth Rodriguez and Magdelys Savigne, OKAN celebrates the release of their debut EP.

Colin Story is a jazz guitarist, writer and teacher based in Toronto. He can be reached at www.colinstory.com, on Instagram and on Twitter.