These are challenging times to be a musician. Empathy and compassion is a crucial part of a pandemic response, but it is easily forgotten in the immediate dangers of trying to protect oneself from an unmasked person, or trying to plan out the next month’s rent without income from performing. For some, returning to work, be it the arts or offices or restaurants, isn’t a matter of choice – it’s the difference between having somewhere to live next month or being able to afford dinner that day. The arts are workplaces with livelihoods on the line and right now, we’re all struggling.

These are challenging times to be a musician. Empathy and compassion is a crucial part of a pandemic response, but it is easily forgotten in the immediate dangers of trying to protect oneself from an unmasked person, or trying to plan out the next month’s rent without income from performing. For some, returning to work, be it the arts or offices or restaurants, isn’t a matter of choice – it’s the difference between having somewhere to live next month or being able to afford dinner that day. The arts are workplaces with livelihoods on the line and right now, we’re all struggling.

For singers and wind musicians in particular, current circumstances are particularly difficult. Crises are intersecting in our arts communities at the moment and are demanding ever more complex responses from the choral world than ever before if we are going to find a way through. There are real and serious dangers to consider as choristers return to action.

Speaking with choristers, there is already so much anxiety and lack of knowledge about how to proceed with doing what we love in a time of pandemic. So it is additionally hard to find oneself in a community of interest where, as in society as a whole, some of those voices are pandemic deniers, vehement anti-maskers, who participate in the pandemic conspiracies and spout the paranoia of “state compliance” and our loss of “bodily sovereignty.” The unfortunate truth is that these people are part of our choirs, part of our choral communities, and they present dangers.

This month, I’m presenting some of my thoughts on recent scientific data and what you can expect from digital rehearsals and upcoming digital concerts.

Lessons Learned from Skagit Valley Chorale

There is growing concern as more and more scientific studies are released about aerosols as a vector for COVID-19 infection. Many different stories have mentioned the Skagit Valley Chorale; one of the earliest was first submitted for review June 15, 2020. It is now the first peer-reviewed study that exclusively focused on the conditions of the outbreak at the case in point. Professor Shelly L. Miller and researchers from across the world published a paper that was fully reviewed and accepted for the journal Indoor Air on September 15, 2020.

The study examined three possible venues for infection: direct contact from fomites (contaminated surfaces); ballistic droplets (from singing); and airborne aerosols. While snacks and chair set-up were mentioned, the index case neither helped set up chairs nor ate snacks. The index case also used the bathroom, but only three other people did as well. Many who ate snacks, touched chairs and did not use the bathroom became ill. After examining in detail, the study found fomites could not be the major mode of transmission.

On ballistic droplets, the seating plan was reviewed. Positive cases were found with no clear pattern, with some cases up to 44 feet from the index case and others behind the person. The study points out the basic physics – that ballistic droplets don’t travel backwards from a mouth – so there’s no reasonable hypothesis that explains how people behind the index case could have been infected by ballistic droplets alone. Furthermore, it is unlikely that ballistic droplets from the index person’s mouth directly fell on the eyes, nostrils, and/or mouth of all the people infected in this rehearsal.

The study concludes that in the absence of data supporting ballistic droplets and fomites, the only other avenue for infection was aerosols – small droplets produced from singing. Low ventilation likely meant that fresh air was not being introduced into the area in sufficient amounts, thus supporting a sufficient viral load in the air, and that choir members breathed in the contaminated air leading to infection.

This superspreader event led to 53 of the 61 singers being infected over the course of the rehearsal with two succumbing to the virus.

At the end of August, a karaoke bar in Quebec City also ended up being the centre of an outbreak. Upwards of 70 people were infected from primary and secondary contact at Bar Kirouac in Quebec City. The spread through contact would eventually reach three schools. The implications of a single event can have major repercussions.

Keep in mind that most choirs in Toronto rehearse in very old churches that have radiators during the winter and open windows during the summer. They don’t have central, forced-air systems to replenish air. The very spaces we rehearse in are important to consider.

Airborne transmission

On Friday, September 18, 2020 the American Center for Disease Control formally changed its guidance on transmission of COVID-19, adding airborne particles. “It is possible that COVID-19 may spread through the droplets and airborne particles that are formed when a person who has COVID-19 coughs, sneezes, sings, talks or breathes.”

Since as early as April, many different public health, engineering and biological experts had raised the concern of airborne transmission of the disease. As more and more research has been conducted, there was sufficient scientific consensus for the CDC to make this change, although, at time of going to press, neither the Public Health Agency of Canada, Public Health Ontario or the World Health Organization had amended their guidance to include airborne transmission as the main mode of transmission. Similarly, Public Health Ontario studied available literature in mid-July exploring transmission risks from singing and playing wind instruments (July 9, 2020) and after a review of multiple studies concluded that transmission is predominantly through large droplet spread (July 16, 2020).

Bizarrely, three days later, on Monday September 21, the CDC pulled its revised guidance. Many journalists and commentators have inferred political interference in the decision.

There’s no shortage of news articles about choir outbreaks. Scientific, peer-reviewed literature is a very important part of ensuring that the most rigorous data reaches our decisionmakers. It can help inform you about the risks you take as a chorister and arts worker, in the audience, and as an arts employer. So the CDC flip-flop is troubling to say the least.

Making Choral rehearsals work over Zoom

“Technical problems, stay tuned, we’ll get this up and running as soon as possible” – is a common refrain in the day and age of livestreams, Facebook Live, Messenger Rooms, FaceTime, and of course, the most common – Zoom.

These aren’t exclusive to the world of choral music. Many a work meeting and conference has been filled with the recurring phrase, “Your microphone is on mute.” This doesn’t make it any less annoying.

So how do you make a choral rehearsal work over Zoom? In short, lots of trial and error. Many choirs are grappling with how to move things into the digital world. Here are a few key takeaways I have for digital events (rehearsal or otherwise):

- Have a designated host whose job is to monitor for trouble, respond to tech issues, and whose focus is the Zoom. This person should not be the presenter/conductor/someone with any other task;

- When rehearsing pronunciations and languages while people are in masks, you won’t hear it right, they won’t hear it right, and no one can distinguish what you’re saying with three layers of fabric and 50 people across the space the size of an NBA basketball court;

- Remind your ensembles that they are valued and loved and address their concerns with validation, support, compassion and empathy. Same goes for your conductors;

- No digital rehearsal can replace the magic of in-person ensemble music-making, so avoid disappointment by accepting that you can’t expect the same end result;

- Try not to be afraid to admit if something doesn’t work and to try something different or new.

The Wonderful World of Digital Concerts

The Wonderful World of Digital Concerts

Virtual Choirs have been common for a while now. They are fun ways to bring together singers from all over the world together into one project. Eric Whitacre’s Virtual Choir project has been the largest and most significant contribution by far to this type of choral presentation. Smaller choirs have long recorded themselves and used these videos on YouTube, livestreams and more. But there have never been choral ensembles that exist solely and purely as virtual ensembles, never singing in person.

YouTube mashups and virtual and remote recordings are a common part of the ecosystem of pop music, especially in the myriad collabs. Using common tech, it’s not hard to make excellent, top-quality videos and recordings of people singing together who are not physically together or even singing at the same time.

For choirs that are turning to electronic versions of what they do, ensemble singing stops being the focus. If 40 choristers are recording their parts separately with the same notes on sheet music, do they still count as an ensemble? Is the conductor now the leader of an ensemble, shaping the sound and musicality, or is it now the video and sound editor ensuring the cues are all lined up and adjusting the balance of the various recordings? We’ll have to see, as virtual rehearsals and digital concerts become more common.

I also have some key takeaways for virtual ensembles:

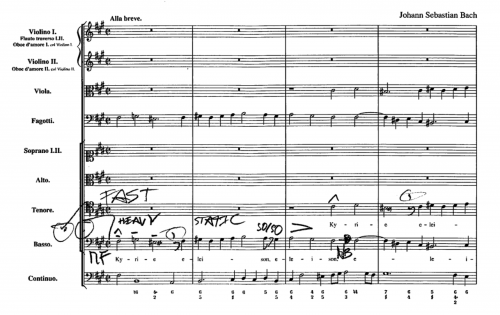

- Mark the music diligently before giving it to choristers and ensure everyone has access to the same music, with updates;

- Breath marks. Breath marks. Breath marks. There’s no sneaking allowed in digital recordings or quiet breaths. If a breath is in the wrong place on a video, it’s obvious. A sound editor has one choice: mute your recording or drastically reduce its sound over that section;

- It can take hours of work and dozens of takes for choristers to find a copy worth submitting. It’s a lot of extra work to do;

- Maintain standards of musical excellence but recognize the layers of obscurity that overlap the end product – low-quality tech, noisy apartment neighbours, uncertainty and fear, lack of rehearsal, and psychological stressors can contribute to a very difficult experience.

October 10 - The Toronto Mendelssohn Choir (of which I am part) is presenting one of the earliest and most significant virtual performances with Kannamma: A Concert of Thanksgiving. As part of its work on anti-racism, the choir has brought in guest curator Suba Sankaran to program the concert alongside new associate conductor, Simon Rivard. Guests include paid members of the Toronto Symphony and Toronto Symphony Youth Orchestra.

Members of the small, elite, professional, paid core of the choir were recorded in advance in a socially distant live session at Trinity-St. Paul’s Centre. Their voices make up the core of the sound and the video. To these professional singers will be added the remainder of the amateur, volunteer, unpaid members of the choir who are recording their sections in isolation at home. The virtual choir will be mixed by video and editing professionals that will make a final cut premiering at the virtual concert.

Follow Brian on Twitter @bjchang. Send info/media/tips to choralscene@thewholenote.com.