Finding Your Voice by Brian W. Hands

Finding Your Voice

Finding Your Voice

by Brian W. Hands

Bastian Publishing

146 pages, illustrations; $16.95

• It seems inevitable for singers to suffer from vocal problems at some point, whether it’s merely a cold, or something lingering, like nodules on their vocal chords. If they happen to be in Toronto, they are likely to end up in the office of laryngologist Dr. Brian Hands, whose practice includes singers from the Canadian Opera Company as well as visiting recitalists. When Hands treats a singer, as he explains in this concise guide to vocal care, he looks not just at the voice but at the singer’s whole lifestyle and general health. Since he sees the voice as a mirror of the soul, for him it actually reflects a singer’s spiritual and emotional state. This holistic approach might be too probing for a singer who is just trying to get through a performance. But fortunately this book is full of advice about dealing practically with all kinds of problems.

“Think of yourself as a vocal athlete,” Hands advises, considering prevention as much as treatment. So that means avoiding parties because of the temptations to talk too loud, eat and drink too much and stay out too late. As well, he advises, “find non-vocal ways to train or discipline children or pets.”

As a doctor, Hands treats the voice divorced from its ability to interpret music. So his glossary defines messa di voce as a vocal exercise rather than the expressive device singers value. But it’s this scientific approach that make this informative book so valuable for all “voice users,” not just singers, but actors, broadcasters, lawyers, auctioneers, teachers and therapists, as well as anyone interested in how the voice works. n

Pamela Margles can be reached at bookshelf@thewholenote.com.

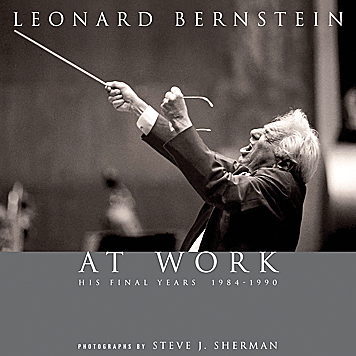

Leonard Bernstein At Work: His Final Years, 1984 – 1990

Leonard Bernstein At Work: His Final Years, 1984 – 1990