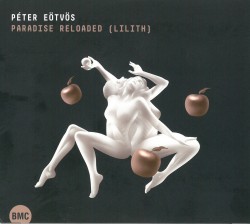

Peter Eötvös: Paradise Reloaded (Lilith) - Annette Schoenmueller; Rebecca Nelsen; Eric Stoklossa; Hungarian RSO; Gregory Vajda

Peter Eötvös – Paradise Reloaded (Lilith)

Peter Eötvös – Paradise Reloaded (Lilith)

Annette Schoenmueller; Rebecca Nelsen; Eric Stoklossa; Hungarian RSO; Gregory Vajda

BMC Records CD 226 (bmcrecords.hu)

In the newly emboldened theocracy, also known as the United States of America, the phrase “God created Adam and Eve” is bandied about to score specific political points. The majority of Bible-thumpers forget, however, that at first it was actually Adam and Lilith. Not created from Adam’s rib, rather, his equal and a powerful being. This is Lilith, who we are pressured to forget in favour of the more feminine, easily yielding Eve. Here we have a major revision of Eötvös’ 2010 opera The Tragedy of the Devil and, in effect, it is an entirely new work.

The axis is the conflict between Lilith and Eve and an exploration of what might have happened, if the first wife of Adam was not thwarted in her efforts to reconcile with him. Lilith, the exiled demon-mother attempts to reload Paradise, and yet loses again. Eötvös, a composer as highly regarded, as he is at times controversial, in this, one of his 12 operas, draws equally on the Viennese tradition of Schoenberg and Berg and on post-war serialism. The fascinating libretto is the work of the Munich-based writer, Albert Ostermaier. The three protagonists and a cast of other characters are accompanied by the Hungarian Radio Symphonic Orchestra, guest-conducted here by Gregory Vajda. This same podium was shared in the past by such titans, as John Barbirolli, Antal Doráti, István Kertész, Otto Klemperer, Neville Mariner and Leopold Stokowski. Biblical proportions, indeed!