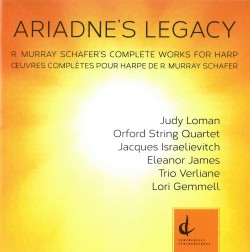

R. Murray Schafer: Ariadne’s Legacy - Judy Loman and Various Artists

R. Murray Schafer – Ariadne’s Legacy

R. Murray Schafer – Ariadne’s Legacy

Judy Loman and Various Artists

Centrediscs CMCCD 23316

(musiccentre.ca)

Judy Loman, principal harpist with the Toronto Symphony Orchestra from 1960 to 2002, is a graduate of the Curtis Institute of Music where she studied with the innovative harpist Carlos Salzedo. In her many years here and abroad she has championed numerous new works for her instrument. Many of these compositions involved Canada’s internationally renowned polymath R. Murray Schafer and in celebration of Loman’s 80th birthday Centrediscs has re-issued from various sources Schafer’s works for the harp in their entirety. Their first collaboration, The Crown of Ariadne (1979), is a technically demanding six-movement suite in which Loman must also play a number of small percussion instruments. It is derived from Schafer’s vast environmental music drama, Patria 5. A companion work, Theseus (1986), was also drawn from this segment of the 12-part Patria series and features Ms. Loman with the Orford String Quartet. Both works involve the extended harp techniques pioneered by Salzedo with delicate, echoing microtonal inflections pitted against incisive percussive effects. Schafer’s subsequent Harp Concerto (1987) is drawn upon a much larger canvas. Its conventional three movements achieve an almost cinematically epic character in this rousing performance by the Toronto Symphony Orchestra led by Andrew Davis.

A second CD devoted to Schafer’s later chamber music features the intimate duet Wild Bird (1997) with violinist Jacques Israelievitch, commissioned by the late TSO concertmaster’s wife and performed with Loman on the occasion of his 50th birthday. Trio (2011) commissioned by the BC-based Trio Verlaine (Lorna McGhee, flute, David Harding, viola, and Heidi Krutzen, harp) was designed as a companion piece to Debussy’s work for the same forces. Here Schafer strikingly abandons the evocative sound events of his earlier works in favour of a persistently linear melodic profile. Among these late works are two vocal settings: Tanzlied (2004) and Four Songs for Mezzo-Soprano and Harp (2011), both sung by Schafer’s life partner and muse, Eleanor James, the former with Loman and the latter with her former student Lori Gemmell. Tanzlied is a setting of verses by Friedrich Nietzsche and includes quotations from that philosopher’s own little-known Lieder. The surprisingly well-mannered Four Songs was initially composed as a wedding present for Schafer’s niece.

It is doubtful that any further harp works will be forthcoming, as Schafer’s program note for these late songs reveals his recent diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. All the more reason then to celebrate these definitive and expertly recorded performances from a golden age.