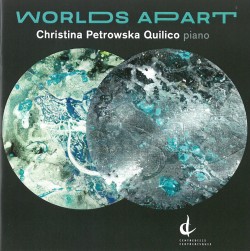

Worlds Apart - Christina Petrowska Quilico

Worlds Apart

Worlds Apart

Christina Petrowska Quilico

Centrediscs CMCCD 23717

Canadian pianist Christina Petrowska Quilico unleashes the eight works here with such immediacy that she creates a special kind of pianistic excitement. Her technique is brilliant, and her imagination boundless. But it’s not just the thrill of the keyboard that drives her – above all you feel the fierce conviction that underlies her vision of each composer’s score.

This is the latest release in Petrowska Quilico’s ongoing recording project covering works from the Canadian piano repertoire. It’s as though she’s out to singlehandedly show just how rich it is. These works were written during a period of just over 20 years, from 1969 to 1992. They all, more or less directly, invoke historical sources – musical, literary or visual.

Peter Paul Koprowski’s Rhapsody on a Theme of Brahms and Steven Gellman’s Fantasia on a Theme of Robert Schumann take full advantage of Petrowska Quilico’s virtuosity. Koprowski gives the elements of Brahms’ Lullaby a Chopinesque treatment, only gradually revealing the familiar theme, while Gellman introduces his theme, from the slow movement of Schumann’s Piano Quintet, then lavishes embellishments.

In Las Meninas, John Rea follows the structure of his source, Schumann’s Scenes from Childhood. But he filters it through his viewing of Velázquez’s iconic, complex painting, Las Meninas by recasting Schumann’s 13 movements in various composers’ styles – Romanticism, impressionism, minimalism, jazz, and so on. Petrowska Quilico has a field day.

Her energy infuses Patrick Cardy’s mythologically based The Masks of Astarte with narrative force. In contrast, her incisive control allows a sense of space to envelop Micheline Coulombe Saint-Marcoux’s lyrical yet monumental Assemblages like a multidimensional sculpture (I thought of Anthony Caro’s works currently on display at the AGO).

In Quivi Sospiri by David Jaeger (who produced this set, and whose writings appear in this magazine), Petrowska Quilico is joined by computer-generated sounds. The rhapsodic yearnings of the piano confront the ominous electronics, then blend in a moving evocation of the sounds that swirl around the hopeless souls condemned to darkness in Dante’s Inferno.

Diana McIntosh’s atmospheric Worlds Apart, which gives this collection its title, weaves a shimmering fabric of intricate patterns. But it’s Geste by Michel-Georges Brégent, Petrowska Quilico’s first husband, who died in 1993, that forms the spiritual heart of this set – especially in the way he invites the performer’s interventions in shaping what happens and when. Brégent’s own description likens his score, mounted on a scroll, to a Calder mobile. In PQ’s hands the sense of urgency never lets up, even in the contemplative passages.

This set certainly showcases Petrowska Quilico’s talents, including her talent as a painter. The painting by her on the booklet cover, called Other Worlds – Light and Dark, beautifully sets the tone for this terrific collection.