Although you couldn’t guess from major record companies’ release schedules, the purpose of a reissue program isn’t to repackage music that has long been available in different formats. It also doesn’t only involve finding unreleased or alternate takes by well-known musicians and sticking them on disc to satisfy completists. Instead, reissues should introduce listeners to important music from the past that has been rarely heard because of distribution system vagaries. This situation has been especially acute when it comes to circulating advanced and/or experimental sounds. Happily, small labels have overcome corporations’ collective blind spots, releasing CDs that create more complete pictures of the musical past, no matter the source. The discs here are part of that process.

Probably the most important find is That Time (NotTwo MW 1001-2), which captures two tracks each from two iterations of the London Jazz Composers Orchestra from 1972 and 1980. Drawn from a period when the LJCO made no professional recordings, the tracks piece together music from radio broadcasts or amateur tapes, sonically rebalanced by a contemporary sound engineer. Although the personnel of the ensemble shrank from 21 to 19 over the eight years, the key participants are accounted for on both dates. Edifyingly each of the four tracks composed by different LJCO members shows off unique group facets. Pianist Howard Riley’s Appolysian, for instance, depends on the keyboard clips and clatters engendered by matching Riley’s vibrating strokes and expressive pummelling with the scalar and circular waves and judders from the string section, which in this case included violinists Phillip Wachsmann and Tony Oxley (who usually plays drums) and bassists Barry Guy and Peter Kowald. Climax occurs when tremolo pianism blends with and smooths out the horn sections’ contributions. Quiet, but with suggestions of metallic minimalist string bowing, trombonist Paul Rutherford’s Quasimode III derives its grounded strength and constant motion from thicker brass expressions and meticulously shaded low-pitched double bass tones. Concentrated power is only briefly interrupted by a dramatic circular-breathing display by soprano saxophonist Evan Parker. Dating from the first session, trumpeter Kenny Wheeler’s Watts Parker Beckett to me Mr Riley? stands out as much for capturing the LJCO in mid-evolution as for its Arcadian beauty. Sophisticatedly arranged, the tune gradually introduces more advanced textures as it advances over Oxley and Paul Lytton’s martial drum slaps and throbs from bassists Guy, Jeff Clyne and Chris Laurence. It pinpoints the group’s transformation though, since the harmonized theme that could come from contemporary TV-show soundtracks is sometimes breached by metal-sharp guitar licks from Derek Bailey, plus stentorian shrieks and split tones from the four trumpeters and six saxophonists.

Probably the most important find is That Time (NotTwo MW 1001-2), which captures two tracks each from two iterations of the London Jazz Composers Orchestra from 1972 and 1980. Drawn from a period when the LJCO made no professional recordings, the tracks piece together music from radio broadcasts or amateur tapes, sonically rebalanced by a contemporary sound engineer. Although the personnel of the ensemble shrank from 21 to 19 over the eight years, the key participants are accounted for on both dates. Edifyingly each of the four tracks composed by different LJCO members shows off unique group facets. Pianist Howard Riley’s Appolysian, for instance, depends on the keyboard clips and clatters engendered by matching Riley’s vibrating strokes and expressive pummelling with the scalar and circular waves and judders from the string section, which in this case included violinists Phillip Wachsmann and Tony Oxley (who usually plays drums) and bassists Barry Guy and Peter Kowald. Climax occurs when tremolo pianism blends with and smooths out the horn sections’ contributions. Quiet, but with suggestions of metallic minimalist string bowing, trombonist Paul Rutherford’s Quasimode III derives its grounded strength and constant motion from thicker brass expressions and meticulously shaded low-pitched double bass tones. Concentrated power is only briefly interrupted by a dramatic circular-breathing display by soprano saxophonist Evan Parker. Dating from the first session, trumpeter Kenny Wheeler’s Watts Parker Beckett to me Mr Riley? stands out as much for capturing the LJCO in mid-evolution as for its Arcadian beauty. Sophisticatedly arranged, the tune gradually introduces more advanced textures as it advances over Oxley and Paul Lytton’s martial drum slaps and throbs from bassists Guy, Jeff Clyne and Chris Laurence. It pinpoints the group’s transformation though, since the harmonized theme that could come from contemporary TV-show soundtracks is sometimes breached by metal-sharp guitar licks from Derek Bailey, plus stentorian shrieks and split tones from the four trumpeters and six saxophonists.

Rutherford, who plays on all the LJCO tracks and German bassist Kowald, who plays on the 1980 ones, also make major contributions to Peter Kowald Quintet (Corbett vs Dempsey CD 0070 corbettvsdempsey.com), the first session under his own name by Kowald (1944-2002). Recorded in 1972 and never previously on CD, the disc’s four group improvisations feature three other Germans: trombonist Günter Christmann, percussionist Paul Lovens and alto saxophonist Peter van de Locht. The saxophonist, who later gave up music for sculpture, is often the odd man out here, with his reed bites and split-tone extensions stacked up against the massed brass reverberations that are further amplified when Kowald plays tuba and alphorn on the brief, final track. Otherwise the music is a close-focused snapshot of European energy music of the time. With Lovens’ clattering drum ruffs and cymbal scratches gluing the beat together alongside double bass strokes, the trombonists have free reign to output every manner of slides, slurs, spits and smears. Plunger tones and tongue flutters also help create a fascinating, ever-shifting sound picture. Pavement Bolognaise, the standout track, is also the longest. A circus of free jazz sonic explorations, it features the three horn players weaving and wavering intersectional trills and irregular vibrations all at once, as metallic bass string thwacks and drum top chops mute distracting excesses like the saxophonist’s screeches in dog-whistle territory. Meanwhile the tune’s centre section showcases a calm oasis of double bass techniques backed only by Lovens’ metal rim patterning and including Kowald’s intricate strokes on all four strings. Variations shake from top to bottom and include thick sul tasto rubs and barely there tweaks.

Rutherford, who plays on all the LJCO tracks and German bassist Kowald, who plays on the 1980 ones, also make major contributions to Peter Kowald Quintet (Corbett vs Dempsey CD 0070 corbettvsdempsey.com), the first session under his own name by Kowald (1944-2002). Recorded in 1972 and never previously on CD, the disc’s four group improvisations feature three other Germans: trombonist Günter Christmann, percussionist Paul Lovens and alto saxophonist Peter van de Locht. The saxophonist, who later gave up music for sculpture, is often the odd man out here, with his reed bites and split-tone extensions stacked up against the massed brass reverberations that are further amplified when Kowald plays tuba and alphorn on the brief, final track. Otherwise the music is a close-focused snapshot of European energy music of the time. With Lovens’ clattering drum ruffs and cymbal scratches gluing the beat together alongside double bass strokes, the trombonists have free reign to output every manner of slides, slurs, spits and smears. Plunger tones and tongue flutters also help create a fascinating, ever-shifting sound picture. Pavement Bolognaise, the standout track, is also the longest. A circus of free jazz sonic explorations, it features the three horn players weaving and wavering intersectional trills and irregular vibrations all at once, as metallic bass string thwacks and drum top chops mute distracting excesses like the saxophonist’s screeches in dog-whistle territory. Meanwhile the tune’s centre section showcases a calm oasis of double bass techniques backed only by Lovens’ metal rim patterning and including Kowald’s intricate strokes on all four strings. Variations shake from top to bottom and include thick sul tasto rubs and barely there tweaks.

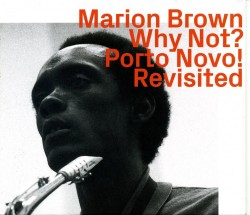

There’s also a European component to American alto saxophonist ezz-thetics 1106 hathut.com), since five of the 13 tracks were recorded in 1967 with Dutch bassist Maarten van Regteren Altena and drummer Han Bennink. The remainder feature Brown with New York cohorts drummer Rashied Ali, pianist Stanley Cowell and bassist Sirone. Known as a member of the harsh 1960s new thing due to his work with Archie Shepp and John Coltrane, Brown (1931-2010), brought an undercurrent of melody to his tonal explorations. Both tendencies are obvious here with the pianist adding to the lyricism by creating whorls and sequenced asides as he follows the saxophonist’s sometimes delicate lead. Playing more conventionally than he would a year later, Brown’s 1966 date outputs lines that could be found on mainstream discs and moves along with space for round-robin contributions from all, including a solid double bass pulse and cymbal-and-bass-drum emphasized solos from Ali. Jokily, Brown ends his combined altissimo and melodic solo on La Sorella with a quote from the Choo’n Gum song and on the extended Homecoming, he quotes Three Blind Mice and the drummer counters with Auld Lang Syne. Homecoming is also the most realized tune, jumping from solemn to staccato and back again as the pianist comps and Brown uncorks bugle-call-like variations and biting flutter tonguing before recapping the head. Showing how quickly improvised music evolved, a year later Altena spends more time double and triple stopping narrow arco slices than he does time-keeping, while Bennink not only thumps his drum kit bellicosely, but begins Porto Novo with a protracted turn on tabla. From the top onwards, Brown also adopts a harder tone, squealing out sheets of sound that often sashay above conventional reed pitches. His slurps and squeaks make common cause with double bass strokes and drum rattles. But the saxophonist maintains enough equilibrium to unexpectedly output a lyrical motif in the midst of jagged tone dissertations on the aptly titled Improvisation. Of its time and yet timeless, Porto Novo, which was the original LP title, manages to successfully incorporate Bennink’s faux-raga tapping, Altena’s repeated tremolo pops and the saxophonist’s split-tone, bird-like peeps into a swaying Spanish-tinged theme that swings while maintaining avant-garde credibility.

There’s also a European component to American alto saxophonist ezz-thetics 1106 hathut.com), since five of the 13 tracks were recorded in 1967 with Dutch bassist Maarten van Regteren Altena and drummer Han Bennink. The remainder feature Brown with New York cohorts drummer Rashied Ali, pianist Stanley Cowell and bassist Sirone. Known as a member of the harsh 1960s new thing due to his work with Archie Shepp and John Coltrane, Brown (1931-2010), brought an undercurrent of melody to his tonal explorations. Both tendencies are obvious here with the pianist adding to the lyricism by creating whorls and sequenced asides as he follows the saxophonist’s sometimes delicate lead. Playing more conventionally than he would a year later, Brown’s 1966 date outputs lines that could be found on mainstream discs and moves along with space for round-robin contributions from all, including a solid double bass pulse and cymbal-and-bass-drum emphasized solos from Ali. Jokily, Brown ends his combined altissimo and melodic solo on La Sorella with a quote from the Choo’n Gum song and on the extended Homecoming, he quotes Three Blind Mice and the drummer counters with Auld Lang Syne. Homecoming is also the most realized tune, jumping from solemn to staccato and back again as the pianist comps and Brown uncorks bugle-call-like variations and biting flutter tonguing before recapping the head. Showing how quickly improvised music evolved, a year later Altena spends more time double and triple stopping narrow arco slices than he does time-keeping, while Bennink not only thumps his drum kit bellicosely, but begins Porto Novo with a protracted turn on tabla. From the top onwards, Brown also adopts a harder tone, squealing out sheets of sound that often sashay above conventional reed pitches. His slurps and squeaks make common cause with double bass strokes and drum rattles. But the saxophonist maintains enough equilibrium to unexpectedly output a lyrical motif in the midst of jagged tone dissertations on the aptly titled Improvisation. Of its time and yet timeless, Porto Novo, which was the original LP title, manages to successfully incorporate Bennink’s faux-raga tapping, Altena’s repeated tremolo pops and the saxophonist’s split-tone, bird-like peeps into a swaying Spanish-tinged theme that swings while maintaining avant-garde credibility.

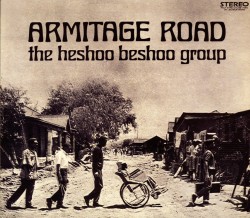

Still, the best argument for maintaining a comprehensive reissue program is to expose new folks to unjustly obscure sounds. Armitage Road by the Heshoo Beshoo Group (We Are Busy Bodies WABB-063 wearebusybodies.com) and Athanor’s Live At The Jazzgalerie Nickelsdorf 1978 (Black-Monk BMCD-03 discogs.com/seller/Black-Monk/profile) fit firmly in that category. The first, from 1970, features a South African quintet of aHenry Sithole, tenor saxophonist Stanley Sithole, guitarist Cyril Magubane, bassist Ernest Mothle and drummer Nelson Magwaza that combined local rhythms and snatches of advanced jazz of the time. The other disc highlights an all-Austrian take on committed free jazz bands like Kowald’s who were playing elsewhere. The quartet consists of alto saxophonist Harun Ghulam Barabbas, trombonist Joseph Traindl, pMuhammad Malli and pianist Richard Ahmad Pechoc, all of whom are as little known today as are the South African crew members. Not that it affects the music, since, as the discs attest, both bands were more interested in making an original statement than in fame. Somewhat unfinished, as are many live dates, the Nickelsdorf disc tracks how the quintet members worked to put their stamp on the evolving Euro-American free jazz idiom. Choosing to extrapolate individual expression, the quartet uses as its base a mid-range Teutonic march tempo, propelled by chunky drum rolls. Never losing track of the exposition during the 70 minutes of pure improvisation, Barabbas, Traindl and to a lesser extent, Pechoc, work through theme variation upon theme variation in multiple pitches and tempos. Sometimes operating in lockstep, players’ strategies can include chromatic reed jumps and plunger trombone wallows along with distinctively directed piano chording. When the horns aren’t riffing call and response, one often propels the theme as the other decorates it, and then they switch roles. As they play cat and mouse with the evolving sounds, although Barabbas can exhibit altissimo, Energy Music-style bites and Traindl up-tempo plunger growls, connective lopes are preferred over unbridled looseness. With Malli’s press rolls and rumbles holding the bottom, the group meanders to a conclusion leaving a memory of sparks ignited for the applauding audience.

Still, the best argument for maintaining a comprehensive reissue program is to expose new folks to unjustly obscure sounds. Armitage Road by the Heshoo Beshoo Group (We Are Busy Bodies WABB-063 wearebusybodies.com) and Athanor’s Live At The Jazzgalerie Nickelsdorf 1978 (Black-Monk BMCD-03 discogs.com/seller/Black-Monk/profile) fit firmly in that category. The first, from 1970, features a South African quintet of aHenry Sithole, tenor saxophonist Stanley Sithole, guitarist Cyril Magubane, bassist Ernest Mothle and drummer Nelson Magwaza that combined local rhythms and snatches of advanced jazz of the time. The other disc highlights an all-Austrian take on committed free jazz bands like Kowald’s who were playing elsewhere. The quartet consists of alto saxophonist Harun Ghulam Barabbas, trombonist Joseph Traindl, pMuhammad Malli and pianist Richard Ahmad Pechoc, all of whom are as little known today as are the South African crew members. Not that it affects the music, since, as the discs attest, both bands were more interested in making an original statement than in fame. Somewhat unfinished, as are many live dates, the Nickelsdorf disc tracks how the quintet members worked to put their stamp on the evolving Euro-American free jazz idiom. Choosing to extrapolate individual expression, the quartet uses as its base a mid-range Teutonic march tempo, propelled by chunky drum rolls. Never losing track of the exposition during the 70 minutes of pure improvisation, Barabbas, Traindl and to a lesser extent, Pechoc, work through theme variation upon theme variation in multiple pitches and tempos. Sometimes operating in lockstep, players’ strategies can include chromatic reed jumps and plunger trombone wallows along with distinctively directed piano chording. When the horns aren’t riffing call and response, one often propels the theme as the other decorates it, and then they switch roles. As they play cat and mouse with the evolving sounds, although Barabbas can exhibit altissimo, Energy Music-style bites and Traindl up-tempo plunger growls, connective lopes are preferred over unbridled looseness. With Malli’s press rolls and rumbles holding the bottom, the group meanders to a conclusion leaving a memory of sparks ignited for the applauding audience.

The outlier of this group of discs is Armitage Road, where the sounds are closer to emerging soul jazz than more expansive avant garde. Still, this strategy may have been the best way a quintet of all Black players could gig in Apartheid-era South Africa. However, the pseudo-Abbey Road cover photo of the band, including wheelchair-bound polio-stricken Magubane crossing a dusty township street, subtly indicates that country’s unequal situation. Magubane wrote most of the tunes and his Steve Cropper via Grant Green-style chording is prominent on all five tracks. Backed by fluid bass work and solid clip-clop drumming, the lilting tunes often depend on twanging guitar riffs and responsive vamps from the Sithole brothers. The gospelish Amabutho (Warrior) and concluding Lazy Bones, which mix a swing groove with electronic vibrations and some slabs of responsive reed honks, offer the meatiest output. Additionally Magubane’s double-stroking solo suggests just how the much the players were holding back. Despite this, the album didn’t yield another Mercy Mercy or Grazin’ in the Grass, clearly the musical role models for the band whose name translates as “moving by force.” Still, those band members who didn’t die young or go into exile – more by-products of the Apartheid system – had extended musical careers, as did most of the players featured on the other CDs. Armitage Road has been reissued by a small Toronto company, a reality reflected in the size of the other labels here. The high-quality output also proves once again that musical values and bigness are often antithetical.

The outlier of this group of discs is Armitage Road, where the sounds are closer to emerging soul jazz than more expansive avant garde. Still, this strategy may have been the best way a quintet of all Black players could gig in Apartheid-era South Africa. However, the pseudo-Abbey Road cover photo of the band, including wheelchair-bound polio-stricken Magubane crossing a dusty township street, subtly indicates that country’s unequal situation. Magubane wrote most of the tunes and his Steve Cropper via Grant Green-style chording is prominent on all five tracks. Backed by fluid bass work and solid clip-clop drumming, the lilting tunes often depend on twanging guitar riffs and responsive vamps from the Sithole brothers. The gospelish Amabutho (Warrior) and concluding Lazy Bones, which mix a swing groove with electronic vibrations and some slabs of responsive reed honks, offer the meatiest output. Additionally Magubane’s double-stroking solo suggests just how the much the players were holding back. Despite this, the album didn’t yield another Mercy Mercy or Grazin’ in the Grass, clearly the musical role models for the band whose name translates as “moving by force.” Still, those band members who didn’t die young or go into exile – more by-products of the Apartheid system – had extended musical careers, as did most of the players featured on the other CDs. Armitage Road has been reissued by a small Toronto company, a reality reflected in the size of the other labels here. The high-quality output also proves once again that musical values and bigness are often antithetical.