Editor's Corner - June 2023

Aux deux hémisphères features two sonatas and three stand-alone works by Quebec cellist and composer Dominique Beauséjour-Ostiguy, accompanied by pianist Jean-Michel Dubé, (Société Métropolitaine du disque SMD 311-1 dominiquebeausejourostiguy.com). Although the CD’s extensive liner notes are unilingual French, the composer’s website gives detailed context in English for the project from which I take the following: “The title is a reference to two of my main sources of inspiration, namely the lyricism and the torment found in Russian post-Romantic music as well as the relentless rhythmic energy of Argentinian tango music. These two hemispheres are very present in my music and represent the two poles of my musical personality. Indeed, my compositions frequently alternate between introversion and extroversion [creating] a cinematographic flavour with a lot of intensity and contrasts. The two hemispheres are also a way of expressing the duality and the complicity between the cello and the piano, constantly in dialogue and each occupying a place of equal importance.” On repeated listening to this disc, the word that kept coming to my mind was “soaring.” The music itself is enthralling, both conventional and adventurous at the same time, and the multi-award-winning performers, are in top form. As pointed out by Terry Robbins elsewhere in these pages, the facilities at Domaine Forget where it was recorded in late 2021 “guaranteeing top-level sound quality,” this album is a real treat for chamber music enthusiasts.

Aux deux hémisphères features two sonatas and three stand-alone works by Quebec cellist and composer Dominique Beauséjour-Ostiguy, accompanied by pianist Jean-Michel Dubé, (Société Métropolitaine du disque SMD 311-1 dominiquebeausejourostiguy.com). Although the CD’s extensive liner notes are unilingual French, the composer’s website gives detailed context in English for the project from which I take the following: “The title is a reference to two of my main sources of inspiration, namely the lyricism and the torment found in Russian post-Romantic music as well as the relentless rhythmic energy of Argentinian tango music. These two hemispheres are very present in my music and represent the two poles of my musical personality. Indeed, my compositions frequently alternate between introversion and extroversion [creating] a cinematographic flavour with a lot of intensity and contrasts. The two hemispheres are also a way of expressing the duality and the complicity between the cello and the piano, constantly in dialogue and each occupying a place of equal importance.” On repeated listening to this disc, the word that kept coming to my mind was “soaring.” The music itself is enthralling, both conventional and adventurous at the same time, and the multi-award-winning performers, are in top form. As pointed out by Terry Robbins elsewhere in these pages, the facilities at Domaine Forget where it was recorded in late 2021 “guaranteeing top-level sound quality,” this album is a real treat for chamber music enthusiasts.

Nuages is another outstanding Canadian cello and piano disc, showcasing Noémie Raymond-Friset and Michel-Alexandre Broekaert respectively, collectively known as Duo Cavatine (KNS Classical KNS A/121 duocavatine.com). The title for this debut disc, which translates as clouds, comes from its centrepiece, producer David Jaeger’s Constable’s Clouds for solo cello. I spoke in my February column about a reworking of this piece with electronics for violist Elizabeth Reid, so I welcomed the opportunity to get to know this original set of variations inspired by the cloud studies of John Constable. Jaeger tells us the variations “of widely differing character” were inspired by the “magical and endless variation we see in the shapes of clouds streaming by.” Raymond-Friset, who gave the work’s premiere, rises to all the technical challenges Jaeger presents in these nuanced nuages. The disc opens with a rarely heard yet charming sonata by Francis Poulenc dating from the occupation years of the Second World War. It’s from the gentle second movement Cavatine that the duo has taken its name. Alfred Schnittke’s powerful Sonata for Cello and Piano No.1 reverses the normal order of things by starting and ending with Largo movements bookending a diabolic moto perpetuo Presto. Throughout the disc, whether in the lyricism of Poulenc or the abrasiveness of Schnittke, Raymond-Friset and Broekaert shine, with technique and musicality to burn. Recorded at Glenn Gould Studio the sound is, as we have come to expect from engineer Dennis Patterson, impeccable.

Nuages is another outstanding Canadian cello and piano disc, showcasing Noémie Raymond-Friset and Michel-Alexandre Broekaert respectively, collectively known as Duo Cavatine (KNS Classical KNS A/121 duocavatine.com). The title for this debut disc, which translates as clouds, comes from its centrepiece, producer David Jaeger’s Constable’s Clouds for solo cello. I spoke in my February column about a reworking of this piece with electronics for violist Elizabeth Reid, so I welcomed the opportunity to get to know this original set of variations inspired by the cloud studies of John Constable. Jaeger tells us the variations “of widely differing character” were inspired by the “magical and endless variation we see in the shapes of clouds streaming by.” Raymond-Friset, who gave the work’s premiere, rises to all the technical challenges Jaeger presents in these nuanced nuages. The disc opens with a rarely heard yet charming sonata by Francis Poulenc dating from the occupation years of the Second World War. It’s from the gentle second movement Cavatine that the duo has taken its name. Alfred Schnittke’s powerful Sonata for Cello and Piano No.1 reverses the normal order of things by starting and ending with Largo movements bookending a diabolic moto perpetuo Presto. Throughout the disc, whether in the lyricism of Poulenc or the abrasiveness of Schnittke, Raymond-Friset and Broekaert shine, with technique and musicality to burn. Recorded at Glenn Gould Studio the sound is, as we have come to expect from engineer Dennis Patterson, impeccable.

Listen to 'Nuages' Now in the Listening Room

In the Pot Pourri section this month you will find Andrew Timar’s thoughtful and informative account of three new discs by the California based Gamelan Sinar Surya, an ensemble devoted to preserving the traditional gamelan music of Indonesia and its diaspora. In contrast, following in the footsteps of his West Coast predecessor Lou Harrison, American composer Brian Baumbusch has created his own instruments in the Balinese tradition while also envisioning new performance practices through innovative building designs and special tunings. He has worked closely with the Balinese ensemble Nata Swara and in 2022 donated his instruments to them and shipped – 1,800 pounds of them – to Bali. He then went to Bali himself to record the album Chemistry for Gamelan and String Quartet with Nata Swara and JACK Quartet (New World Records 80833-2 newworldrecords.org/search?q=Brian+Baumbusch). The disc opens with the exhilarating Prisms for Gene Davis for gamelan, completed in 2021, the most recent work presented. This is followed by Three Elements for String Quartet (2016), Helium, Lithium and Mercury. Performed by JACK, the work, an extreme example of Baumbusch’s “polytempo” style, features close harmonies and some abrasive textures amid doppler effects and the breakneck speed of its final movement. The disc closes with Hydrogen(2)Oxygen (2015) featuring both ensembles. The work reconsiders the earlier Bali Alloy for quartet and gamelan in which the composer attempted to unite the disparate instruments. This later work takes into consideration the irreconcilability of its two sound worlds, i.e. the harmonic overtone series naturally produced by the string instruments and the inharmonic series of partials of the steel and cedar bars of the gamelan instruments. This allows the string quartet and gamelan to exist side-by-side, exploiting their combinations and contrasts for expressive effect; in the words of Stephen Brooke after the premiere, “building from an ethereal opening into a raging torrent of asymmetrical rhythms, phase-shifting patterns and beautifully strange harmonies [...] magnificent, and as intoxicating as a drug.”

In the Pot Pourri section this month you will find Andrew Timar’s thoughtful and informative account of three new discs by the California based Gamelan Sinar Surya, an ensemble devoted to preserving the traditional gamelan music of Indonesia and its diaspora. In contrast, following in the footsteps of his West Coast predecessor Lou Harrison, American composer Brian Baumbusch has created his own instruments in the Balinese tradition while also envisioning new performance practices through innovative building designs and special tunings. He has worked closely with the Balinese ensemble Nata Swara and in 2022 donated his instruments to them and shipped – 1,800 pounds of them – to Bali. He then went to Bali himself to record the album Chemistry for Gamelan and String Quartet with Nata Swara and JACK Quartet (New World Records 80833-2 newworldrecords.org/search?q=Brian+Baumbusch). The disc opens with the exhilarating Prisms for Gene Davis for gamelan, completed in 2021, the most recent work presented. This is followed by Three Elements for String Quartet (2016), Helium, Lithium and Mercury. Performed by JACK, the work, an extreme example of Baumbusch’s “polytempo” style, features close harmonies and some abrasive textures amid doppler effects and the breakneck speed of its final movement. The disc closes with Hydrogen(2)Oxygen (2015) featuring both ensembles. The work reconsiders the earlier Bali Alloy for quartet and gamelan in which the composer attempted to unite the disparate instruments. This later work takes into consideration the irreconcilability of its two sound worlds, i.e. the harmonic overtone series naturally produced by the string instruments and the inharmonic series of partials of the steel and cedar bars of the gamelan instruments. This allows the string quartet and gamelan to exist side-by-side, exploiting their combinations and contrasts for expressive effect; in the words of Stephen Brooke after the premiere, “building from an ethereal opening into a raging torrent of asymmetrical rhythms, phase-shifting patterns and beautifully strange harmonies [...] magnificent, and as intoxicating as a drug.”

There are times when Baumbusch’s textures sound unearthly and it’s hard to reconcile the sounds with acoustic instruments. The same is true of Jason Doell’s Becoming in Shadows – Of Being Touched (Whited Sepulchre Records WSR043 jasondoell.com), although in this instance there are electronic manipulations at work. All the sound materials originate from the composer’s daily piano improvisations recorded while in residency at the Banff Centre in early 2020 (although some of it seems to have been performed by Mauro Zannoli on a “frozen” piano, exhumed from a snowbank). These are, to greater and lesser degrees, subjected to a piece of simple generative music software developed by Doell. The program blends user-defined parameters with decision-making procedures to determine how sounds from an audio database are strung together, layered and transformed, all the while guided by the composer’s aesthetic. A kind of humanized AI design. The result is a dreamlike landscape, a labyrinthine journey where microtonal pitches are blended with soft percussive sounds, all recognizable as emanating from a piano, albeit an otherworldly one.

There are times when Baumbusch’s textures sound unearthly and it’s hard to reconcile the sounds with acoustic instruments. The same is true of Jason Doell’s Becoming in Shadows – Of Being Touched (Whited Sepulchre Records WSR043 jasondoell.com), although in this instance there are electronic manipulations at work. All the sound materials originate from the composer’s daily piano improvisations recorded while in residency at the Banff Centre in early 2020 (although some of it seems to have been performed by Mauro Zannoli on a “frozen” piano, exhumed from a snowbank). These are, to greater and lesser degrees, subjected to a piece of simple generative music software developed by Doell. The program blends user-defined parameters with decision-making procedures to determine how sounds from an audio database are strung together, layered and transformed, all the while guided by the composer’s aesthetic. A kind of humanized AI design. The result is a dreamlike landscape, a labyrinthine journey where microtonal pitches are blended with soft percussive sounds, all recognizable as emanating from a piano, albeit an otherworldly one.

Concert Note: On June 18 at Array Space the TONE Festival features Jason Doell as he launches his album Becoming In Shadows ~ Of Being Touched.

Although there is an electronic aspect on one of the tracks of Christina Petrowska Quilico’s latest CD Blaze featuring piano music of Alice Ping Yee Ho (Centrediscs CMCCD 31323 cmccanada.org/product-category/recordings/Centrediscs), the rest are purely acoustic. Ho tells us “The eight works in this collection have short, descriptive titles, with inspiration drawn from abstract paintings, forces of nature, the last journey of a female pilot, a horror film, plus a show piece from a piano competition. These compositions are both introspective and personal, designed to elicit evocative ‘images’ or ‘impressions,’ visually and psychologically. It is a great honour to have these works recorded by Christina Petrowska Quilico, an astounding musician as well as an acclaimed visual artist. The poetic metaphors in these pieces not only showcase her powerful performer’s persona but also uniquely resonate with her beautiful and vibrant paintings.” Among the paintings depicted are Van Gogh’s Starry Night and Dali’s The Persistence of Memory. Erupting Skies evokes Amelia Earhart’s last journey: “The solo piano is a symbolic representation of a female voice; […] the electronic track is a combination of Earhart’s voice with multiple layers of engineered acoustic and synthesized sounds.” The range of emotions depicted and the sheer virtuosity of several of the works make demands on the pianist that a lesser musician would find daunting. Petrowska Quilico, still at the top of her game after more than 50 recordings, rises to every challenge without breaking a sweat. Stay tuned for the upcoming Centrediscs release Shadow & Light, a double concerto CD with Petrowska Quilico and violinist Marc Djokic with Sinfonia Toronto under Nurhan Arman featuring music by Ho, Christos Hatzis and Larissa Kuzmenko.

Although there is an electronic aspect on one of the tracks of Christina Petrowska Quilico’s latest CD Blaze featuring piano music of Alice Ping Yee Ho (Centrediscs CMCCD 31323 cmccanada.org/product-category/recordings/Centrediscs), the rest are purely acoustic. Ho tells us “The eight works in this collection have short, descriptive titles, with inspiration drawn from abstract paintings, forces of nature, the last journey of a female pilot, a horror film, plus a show piece from a piano competition. These compositions are both introspective and personal, designed to elicit evocative ‘images’ or ‘impressions,’ visually and psychologically. It is a great honour to have these works recorded by Christina Petrowska Quilico, an astounding musician as well as an acclaimed visual artist. The poetic metaphors in these pieces not only showcase her powerful performer’s persona but also uniquely resonate with her beautiful and vibrant paintings.” Among the paintings depicted are Van Gogh’s Starry Night and Dali’s The Persistence of Memory. Erupting Skies evokes Amelia Earhart’s last journey: “The solo piano is a symbolic representation of a female voice; […] the electronic track is a combination of Earhart’s voice with multiple layers of engineered acoustic and synthesized sounds.” The range of emotions depicted and the sheer virtuosity of several of the works make demands on the pianist that a lesser musician would find daunting. Petrowska Quilico, still at the top of her game after more than 50 recordings, rises to every challenge without breaking a sweat. Stay tuned for the upcoming Centrediscs release Shadow & Light, a double concerto CD with Petrowska Quilico and violinist Marc Djokic with Sinfonia Toronto under Nurhan Arman featuring music by Ho, Christos Hatzis and Larissa Kuzmenko.

If it is due to the efforts of Christina Petrowska Quilico that we are aware of as many Canadian women composers as we are, it is thanks to American pianist Sarah Cahill that the world is becoming increasingly aware of the presence of women composers throughout history. The Future is Female (firsthandrecords.com) is a project launched in March 2022 encompassing 30 composers ranging from Elisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre (1665-1729) to the more familiar 19th and early 20th-century names of Clara Schumann, Fanny Mendelssohn-Hensel and Germaine Tailleferre, and on into modern times with two dozen more including Betsy Jolas and Meredith Monk to name just a couple. Bringing the series to a close, Vol. 3 At Play (FHR133) was released in May 2023 and features works by Hélène de Montgeroult (1764-1836), Cécile Chaminade, Grażyna Bacewicz, Chen Yi, Franghiz Ali-Zadeh, Pauline Oliveros, Hannah Kendall, Aida Shirazi and Regina Harris Baiocchi, pieces by the last four having been composed in the 21st century. Cahill says “Like most pianists, I grew up with the classical canon, which has always excluded women composers as well as composers of color. It is still standard practice to perform recitals consisting entirely of music written by men. The Future is Female, then, aims to be a corrective towards rebalancing the repertoire. It does not attempt to be exhaustive, in any way, and the three albums represent only a small fraction of the music by women which is waiting to be performed and heard.” Each of the three volumes has a theme – In Nature, The Dance and At Play – and is arranged chronologically, with ten works spanning three centuries per CD. In this way each recital brings a fresh perspective and expands our understanding of the history of Western music from the classical to the modern era. Kudos to Cahill for convincing performances of the music of all these diverse styles and composers, for giving them voice and for opening our eyes and ears.

If it is due to the efforts of Christina Petrowska Quilico that we are aware of as many Canadian women composers as we are, it is thanks to American pianist Sarah Cahill that the world is becoming increasingly aware of the presence of women composers throughout history. The Future is Female (firsthandrecords.com) is a project launched in March 2022 encompassing 30 composers ranging from Elisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre (1665-1729) to the more familiar 19th and early 20th-century names of Clara Schumann, Fanny Mendelssohn-Hensel and Germaine Tailleferre, and on into modern times with two dozen more including Betsy Jolas and Meredith Monk to name just a couple. Bringing the series to a close, Vol. 3 At Play (FHR133) was released in May 2023 and features works by Hélène de Montgeroult (1764-1836), Cécile Chaminade, Grażyna Bacewicz, Chen Yi, Franghiz Ali-Zadeh, Pauline Oliveros, Hannah Kendall, Aida Shirazi and Regina Harris Baiocchi, pieces by the last four having been composed in the 21st century. Cahill says “Like most pianists, I grew up with the classical canon, which has always excluded women composers as well as composers of color. It is still standard practice to perform recitals consisting entirely of music written by men. The Future is Female, then, aims to be a corrective towards rebalancing the repertoire. It does not attempt to be exhaustive, in any way, and the three albums represent only a small fraction of the music by women which is waiting to be performed and heard.” Each of the three volumes has a theme – In Nature, The Dance and At Play – and is arranged chronologically, with ten works spanning three centuries per CD. In this way each recital brings a fresh perspective and expands our understanding of the history of Western music from the classical to the modern era. Kudos to Cahill for convincing performances of the music of all these diverse styles and composers, for giving them voice and for opening our eyes and ears.

Some half a century ago I spent many hours at my kitchen table trying to figure out a song from Bruce Cockburn’s eponymous first album, the inaugural release on Bernie Finkelstein’s True North Records label. That song, Thoughts on a Rainy Afternoon, has recently come back into my repertoire thanks to guitarist Brian Katz who attended one of my backyard music gatherings last fall. It’s taken a while to get my chops back for Cockburn’s intricate chord progressions and finger patterns, but it’s been worth the effort. So imagine the pleasure I felt to find Cockburn’s O Sun O Moon (True North Records TND811 truenorthrecords.com), in my inbox last month. Over the years Cockburn’s music has gone through changes from that pristine acoustic first offering through many sides of pop music and hard-edged songs, but he has always maintained his moral compass, celebrating life and protesting abuse and ignorance. On his latest album the opening track On a Roll is reminiscent of some of his rockier outings, but the overall feel of the disc is gentle and, as always, thoughtful and thought-provoking. Predominantly acoustic, Cockburn plays guitar, resonator guitar and dulcimer and is joined by a handful of A-list musicians including guitarist Colin Linden, who also produced the recording, with vocal support from Shawn Colvin, Susan Aglukark, Allison Russell and Ann and Regina McCrary. Highlights include the mournful yet anthemic Colin Went Down to the Water, When the Spirit Walks In the Room with violinist Jenny Scheinman and Janice Powers on B3 organ, the cryptic King of the Bolero – who is it plays like that? – and the instrumental Haiku. Cockburn’s voice has weathered somewhat over time, but he uses the gruffness to good effect, and he has not lost any of his musical charm or character. “O Sun by day o moon by night | Light my way so I get this right | And if that sun and moon don’t shine | Heaven guide these feet of mine – to Glory…”

Some half a century ago I spent many hours at my kitchen table trying to figure out a song from Bruce Cockburn’s eponymous first album, the inaugural release on Bernie Finkelstein’s True North Records label. That song, Thoughts on a Rainy Afternoon, has recently come back into my repertoire thanks to guitarist Brian Katz who attended one of my backyard music gatherings last fall. It’s taken a while to get my chops back for Cockburn’s intricate chord progressions and finger patterns, but it’s been worth the effort. So imagine the pleasure I felt to find Cockburn’s O Sun O Moon (True North Records TND811 truenorthrecords.com), in my inbox last month. Over the years Cockburn’s music has gone through changes from that pristine acoustic first offering through many sides of pop music and hard-edged songs, but he has always maintained his moral compass, celebrating life and protesting abuse and ignorance. On his latest album the opening track On a Roll is reminiscent of some of his rockier outings, but the overall feel of the disc is gentle and, as always, thoughtful and thought-provoking. Predominantly acoustic, Cockburn plays guitar, resonator guitar and dulcimer and is joined by a handful of A-list musicians including guitarist Colin Linden, who also produced the recording, with vocal support from Shawn Colvin, Susan Aglukark, Allison Russell and Ann and Regina McCrary. Highlights include the mournful yet anthemic Colin Went Down to the Water, When the Spirit Walks In the Room with violinist Jenny Scheinman and Janice Powers on B3 organ, the cryptic King of the Bolero – who is it plays like that? – and the instrumental Haiku. Cockburn’s voice has weathered somewhat over time, but he uses the gruffness to good effect, and he has not lost any of his musical charm or character. “O Sun by day o moon by night | Light my way so I get this right | And if that sun and moon don’t shine | Heaven guide these feet of mine – to Glory…”

That first True North Record was produced by Eugene Martynec, as were many of the label’s subsequent offerings including, in that same inaugural year, the haunting track December Angel on Long Lost Relatives by Syrinx, a seminal Toronto electronic ensemble featuring the synthesizers of John Mills-Cockell. Martynec is still an active part of the Toronto music scene, albeit after spending some years abroad, and his current project is the free improvising collective Gilliam | Martynec | McBirnie in which he’s in charge of electroacoustics, with pianist Bill Gilliam and flutist Bill McBirnie. Their latest release, Outside the Maze (gilliammcbirniemartynec.bandcamp.com/album/outside-the-maze), consists of ten diverse tracks, no two of which sound the same. While the piano and flutes (C and alto) are pretty much distinguishable throughout, Martynec’s contributions vary from atmospheric to percussive. At times it is hard to imagine the convincing sounds are not being created on physical drums and cymbals; at others it’s hard to imagine what their origins are. It’s also hard to imagine that these cohesive “compositions” are being created spontaneously in real time without premeditation or formal structure. The results are entrancing.

That first True North Record was produced by Eugene Martynec, as were many of the label’s subsequent offerings including, in that same inaugural year, the haunting track December Angel on Long Lost Relatives by Syrinx, a seminal Toronto electronic ensemble featuring the synthesizers of John Mills-Cockell. Martynec is still an active part of the Toronto music scene, albeit after spending some years abroad, and his current project is the free improvising collective Gilliam | Martynec | McBirnie in which he’s in charge of electroacoustics, with pianist Bill Gilliam and flutist Bill McBirnie. Their latest release, Outside the Maze (gilliammcbirniemartynec.bandcamp.com/album/outside-the-maze), consists of ten diverse tracks, no two of which sound the same. While the piano and flutes (C and alto) are pretty much distinguishable throughout, Martynec’s contributions vary from atmospheric to percussive. At times it is hard to imagine the convincing sounds are not being created on physical drums and cymbals; at others it’s hard to imagine what their origins are. It’s also hard to imagine that these cohesive “compositions” are being created spontaneously in real time without premeditation or formal structure. The results are entrancing.

A final quick note about Toronto’s Latin diva Eliana Cuevas’ latest release Seré Libre (Alma Records ACD472323 shopalmarecords.com). The Venezuelan-Canadian singer is accompanied by the Angel Falls Orchestra – named for the world’s highest waterfall located in Canaima National Park, Venezuela – conducted by the album’s producer Jeremy Ledbetter. Cuevas says “I created this 27-piece orchestra, as it was the one missing piece to realize my dream of fusing the incredibly rich traditions of Venezuelan folk rhythms and classical music.” The album explores loss – the deaths of Cuevas’ father and grandfather – and her mission to continue the centuries old folk music traditions they taught her. The title song, which translates as “I shall be free,” is a nine-minute epic journey which Cuevas says she always dedicates to her troubled homeland, but “it can be interpreted as being about finding freedom from whatever is holding you back.” With Cuevas’ gorgeous voice and the lush orchestrations played by an orchestra that includes many of Toronto’s finest pit musicians, this is truly a glorious album. There will also be a theatrical film release of the project which will be available online by the time you read this.

A final quick note about Toronto’s Latin diva Eliana Cuevas’ latest release Seré Libre (Alma Records ACD472323 shopalmarecords.com). The Venezuelan-Canadian singer is accompanied by the Angel Falls Orchestra – named for the world’s highest waterfall located in Canaima National Park, Venezuela – conducted by the album’s producer Jeremy Ledbetter. Cuevas says “I created this 27-piece orchestra, as it was the one missing piece to realize my dream of fusing the incredibly rich traditions of Venezuelan folk rhythms and classical music.” The album explores loss – the deaths of Cuevas’ father and grandfather – and her mission to continue the centuries old folk music traditions they taught her. The title song, which translates as “I shall be free,” is a nine-minute epic journey which Cuevas says she always dedicates to her troubled homeland, but “it can be interpreted as being about finding freedom from whatever is holding you back.” With Cuevas’ gorgeous voice and the lush orchestrations played by an orchestra that includes many of Toronto’s finest pit musicians, this is truly a glorious album. There will also be a theatrical film release of the project which will be available online by the time you read this.

Listen to 'Seré Libre' Now in the Listening Room

We invite submissions. CDs, DVDs and comments should be sent to: DISCoveries, WholeNote Media Inc., The Centre for Social Innovation, 503 – 720 Bathurst St. Toronto ON M5S 2R4.

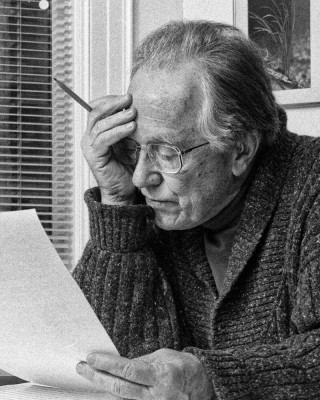

David Olds, DISCoveries Editor

discoveries@thewholenote.com