Editor's Corner - February 2020

This month Tapestry presents the world premiere of American composer Luna Pearl Woolf’s latest opera, Jacqueline. Coinciding with this is the Pentatone release of Woolf’s Fire and Flood on the Oxingale label (PTC5186803 naxosdirect.com). This striking vocal disc features mostly recent works for a cappella choir (the Choir of Trinity Wall Street under the direction of Julian Wachner) with soloists in several instances and, in the most memorable selection, Après moi, le déluge, obbligato cello (Matt Haimovitz). After a virtuosic cello cadenza, this work develops into a bluesy and occasionally meditative telling of the story of Noah and the Flood which culminates in the gospel-tinged Lord, I’m goin’ down in Louisiana before gently subsiding. After a rousing arrangement of Leonard Cohen’s Everybody Knows for vocal trio and cello, comes a modern-sounding but fairly tonal Missa in Fines Orbis Terrae with the choir accompanied by Messiaen-like organ (Avi Stein). The vocal trio (sopranos Devon Guthrie and Nancy Anderson with mezzo Elise Quagliata) return for One to One to One, in this instance accompanied by the low strings (three cellos and three basses) of NOVUS NY. Having begun with the close harmonies, murmurs, shouts and extended vocal techniques of the a cappella To the Fire with full choir, the disc ends with the vocal trio once again joined by Haimovitz for a raucous setting of Cohen’s Who by Fire to close out an exceptional disc. A wonderful cross-section of Woolf’s vocal writing that bodes well for the new opera.

This month Tapestry presents the world premiere of American composer Luna Pearl Woolf’s latest opera, Jacqueline. Coinciding with this is the Pentatone release of Woolf’s Fire and Flood on the Oxingale label (PTC5186803 naxosdirect.com). This striking vocal disc features mostly recent works for a cappella choir (the Choir of Trinity Wall Street under the direction of Julian Wachner) with soloists in several instances and, in the most memorable selection, Après moi, le déluge, obbligato cello (Matt Haimovitz). After a virtuosic cello cadenza, this work develops into a bluesy and occasionally meditative telling of the story of Noah and the Flood which culminates in the gospel-tinged Lord, I’m goin’ down in Louisiana before gently subsiding. After a rousing arrangement of Leonard Cohen’s Everybody Knows for vocal trio and cello, comes a modern-sounding but fairly tonal Missa in Fines Orbis Terrae with the choir accompanied by Messiaen-like organ (Avi Stein). The vocal trio (sopranos Devon Guthrie and Nancy Anderson with mezzo Elise Quagliata) return for One to One to One, in this instance accompanied by the low strings (three cellos and three basses) of NOVUS NY. Having begun with the close harmonies, murmurs, shouts and extended vocal techniques of the a cappella To the Fire with full choir, the disc ends with the vocal trio once again joined by Haimovitz for a raucous setting of Cohen’s Who by Fire to close out an exceptional disc. A wonderful cross-section of Woolf’s vocal writing that bodes well for the new opera.

Last April I wrote about a solo recording by Icelandic cellist Sæunn Thorsteinsdóttir called Vernacular which included Afterquake by Páll Ragnar Pálsson, a rock musician who has recently come to the world of art music. That solo piece was directly linked to his earlier Quake for cello and chamber orchestra, a concerto in all but name and his first collaboration with Thorsteinsdóttir. On a new disc from Sono Luminus, Concurrence (DSL-92237 sonoluminus.com) Thorsteinsdóttir is heard performing this forebear with the Iceland Symphony Orchestra under the direction of Daniel Bjarnason, the orchestra’s principal guest conductor. While I find Afterquake a stunning tour de force with its virtuosity and subtlety, I welcome this opportunity to hear the original Quake with its expanded palette of timbre, texture and colour. It is no surprise that it was a selected work at the International Rostrum of Composers in Budapest in 2018. The disc also includes Metacosmos, an atmospheric work by Anna Thorvaldsdóttir, Haukur Tómasson’s Piano Concerto No.2 and María Huld Markan Sigfúsdóttir’s Oceans. In the booklet essay by American critic Steve Smith we are urged to contemplate the human dimensions of the music and not just hear it as scenic paintings. I must confess though, from the opening strains of Metacosmos I found myself remembering the stark landscapes of Iceland and thinking that yes, “You can hear a country in its music.” Tómasson’s concerto is seemingly all about timbre, the dynamics range from delicate pianissimos to forceful fortes, but the music is never bombastic. As Smith says, “the soloist [Víkingur Ólafsson] is first among equals, a frolicsome force in continual conversation with lively choruses of counterparts, never overshadowed but also rarely isolated.” Sigfúsdóttir’s Oceans begins in near silence, gently evoking sunrise on a quiet sea. The seven-minute piece remains calm and serene throughout, setting the stage for Pálsson’s Quake, which concludes the disc. The recordings were made in the main Eldborg concert hall and the Norðurljós recital hall of Reykjavik’s five-star waterfront cultural centre Harpa, using Pyramix software, with the orchestra seated in a circle around the conductor. Production values are superb, with both CD and Blu-ray Pure Audio discs included in the package. Highly recommended.

Last April I wrote about a solo recording by Icelandic cellist Sæunn Thorsteinsdóttir called Vernacular which included Afterquake by Páll Ragnar Pálsson, a rock musician who has recently come to the world of art music. That solo piece was directly linked to his earlier Quake for cello and chamber orchestra, a concerto in all but name and his first collaboration with Thorsteinsdóttir. On a new disc from Sono Luminus, Concurrence (DSL-92237 sonoluminus.com) Thorsteinsdóttir is heard performing this forebear with the Iceland Symphony Orchestra under the direction of Daniel Bjarnason, the orchestra’s principal guest conductor. While I find Afterquake a stunning tour de force with its virtuosity and subtlety, I welcome this opportunity to hear the original Quake with its expanded palette of timbre, texture and colour. It is no surprise that it was a selected work at the International Rostrum of Composers in Budapest in 2018. The disc also includes Metacosmos, an atmospheric work by Anna Thorvaldsdóttir, Haukur Tómasson’s Piano Concerto No.2 and María Huld Markan Sigfúsdóttir’s Oceans. In the booklet essay by American critic Steve Smith we are urged to contemplate the human dimensions of the music and not just hear it as scenic paintings. I must confess though, from the opening strains of Metacosmos I found myself remembering the stark landscapes of Iceland and thinking that yes, “You can hear a country in its music.” Tómasson’s concerto is seemingly all about timbre, the dynamics range from delicate pianissimos to forceful fortes, but the music is never bombastic. As Smith says, “the soloist [Víkingur Ólafsson] is first among equals, a frolicsome force in continual conversation with lively choruses of counterparts, never overshadowed but also rarely isolated.” Sigfúsdóttir’s Oceans begins in near silence, gently evoking sunrise on a quiet sea. The seven-minute piece remains calm and serene throughout, setting the stage for Pálsson’s Quake, which concludes the disc. The recordings were made in the main Eldborg concert hall and the Norðurljós recital hall of Reykjavik’s five-star waterfront cultural centre Harpa, using Pyramix software, with the orchestra seated in a circle around the conductor. Production values are superb, with both CD and Blu-ray Pure Audio discs included in the package. Highly recommended.

The String Orchestra of Brooklyn (SOB)’s conductor Eli Spindel says of the group’s debut CD release afterimage (Furious Artisans FACD6823 furiousartisans.com) “The featured works […] take as their starting point a single moment from an older work and – through processes of repetition, distortion, and in the case of the Stabat Mater, extreme slow motion – create a completely new soundscape, like opening a small door into an unfamiliar world.” The disc begins with Christopher Cerrone’s High Windows, based on Paganini’s Caprice No.6 in G Minor. Scored for string quartet and string orchestra, the SOB is joined on this recording by the Argus Quartet. The 13-minute work examines a fragment of the Paganini as under a microscope and also draws on material from an earlier Cerrone piece for piano and electronics. The title refers to the windows of the church in which the premiere performance took place. Although this is the SOB’s first recording, they were founded in 2007 and the second work is Jacob Cooper’s Stabat Mater Dolorosa which was written for them in 2009. Taking Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater as its point of departure, the 27-minute work incorporates two singers as does the original. It takes patience to listen to the extremely slow unfolding of this careful examination of one of the most gorgeous works of early 18th-century vocal repertoire. If you are able to suspend your disbelief, it’s well worth the journey. The disc also includes the original works that inspired Cerrone and Cooper. Violinist Rachel Lee Priday performs Paganini’s solo caprice and soprano Mellissa Hughes and mezzo Kate Maroney shine in a more traditional interpretation of the first movement of Pergolesi’s masterpiece to complete the disc. My only quibble with this recording is the order of presentation. I’m sure much thought went into the decision to put the new works first and the old works last, but after several listenings I find I prefer to hear the Paganini first to set the stage for Cerrone’s tribute, then the Cooper, with Pergolesi last to really bring us home.

The String Orchestra of Brooklyn (SOB)’s conductor Eli Spindel says of the group’s debut CD release afterimage (Furious Artisans FACD6823 furiousartisans.com) “The featured works […] take as their starting point a single moment from an older work and – through processes of repetition, distortion, and in the case of the Stabat Mater, extreme slow motion – create a completely new soundscape, like opening a small door into an unfamiliar world.” The disc begins with Christopher Cerrone’s High Windows, based on Paganini’s Caprice No.6 in G Minor. Scored for string quartet and string orchestra, the SOB is joined on this recording by the Argus Quartet. The 13-minute work examines a fragment of the Paganini as under a microscope and also draws on material from an earlier Cerrone piece for piano and electronics. The title refers to the windows of the church in which the premiere performance took place. Although this is the SOB’s first recording, they were founded in 2007 and the second work is Jacob Cooper’s Stabat Mater Dolorosa which was written for them in 2009. Taking Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater as its point of departure, the 27-minute work incorporates two singers as does the original. It takes patience to listen to the extremely slow unfolding of this careful examination of one of the most gorgeous works of early 18th-century vocal repertoire. If you are able to suspend your disbelief, it’s well worth the journey. The disc also includes the original works that inspired Cerrone and Cooper. Violinist Rachel Lee Priday performs Paganini’s solo caprice and soprano Mellissa Hughes and mezzo Kate Maroney shine in a more traditional interpretation of the first movement of Pergolesi’s masterpiece to complete the disc. My only quibble with this recording is the order of presentation. I’m sure much thought went into the decision to put the new works first and the old works last, but after several listenings I find I prefer to hear the Paganini first to set the stage for Cerrone’s tribute, then the Cooper, with Pergolesi last to really bring us home.

Listen to 'afterimage' Now in the Listening Room

I thought I had all the material I needed for this month’s column when, just a few days before deadline, we received a shipment from the label Cold Blue and I found one of the discs so similar in approach to Cooper’s Stabat Mater that I decided to add it to my pile. Although new to me, it seems that Jim Fox originally founded this label in 1983, producing 10- and later 12-inch vinyl discs of primarily California-based contemporary and avant-garde music. When both of its distributors closed their doors in 1985 the label ceased operations for a time, but Fox later re-established it and began producing CDs in 2000. The catalogue now includes some five dozen titles by a host of composers including Fox himself, John Luther Adams, Charlemagne Palestine, Larry Polansky, Kyle Gann and Daniel Lenz to name but a few (i.e. the ones I’ve heard of). The disc that captured my attention is Matt Sargent – Separation Songs (CB0055 coldbluemusic.com), a set of 54 variations on selections from William Billings’ New England Psalm Singer. Composed between 2013 and 2018, Sargent has scored these four-voice hymn tunes, originally published in 1770, for two string quartets. On this recording the Eclipse Quartet accompanies and interacts with itself through overdubbing. Sargent says: “Throughout the piece, hymns tunes appear and reappear in ever-expanding loops of music passed between the quartets. Each time they return, the tunes filter through a ‘separation process’ whereby selected notes migrate from one quartet to the other. This process leaves breaks in the music that either remain silent or are filled in by stretching the durations of nearby notes, generating new rhythms and harmonies.” To my ears, the effect is like listening to a Renaissance consort of viols through a layer of gauze, or filtered by the mists of time, much like when ghostly strains of Schubert’s Death and the Maiden appear in George Crumb’s Black Angels. If I said you would need patience for Cooper’s protracted Stabat Mater, that is more than doubly the case for this 73-minute, one-track composition, but again, it rewards every moment of attention. I look forward to exploring the Cold Blue back catalogue, and to future releases.

I thought I had all the material I needed for this month’s column when, just a few days before deadline, we received a shipment from the label Cold Blue and I found one of the discs so similar in approach to Cooper’s Stabat Mater that I decided to add it to my pile. Although new to me, it seems that Jim Fox originally founded this label in 1983, producing 10- and later 12-inch vinyl discs of primarily California-based contemporary and avant-garde music. When both of its distributors closed their doors in 1985 the label ceased operations for a time, but Fox later re-established it and began producing CDs in 2000. The catalogue now includes some five dozen titles by a host of composers including Fox himself, John Luther Adams, Charlemagne Palestine, Larry Polansky, Kyle Gann and Daniel Lenz to name but a few (i.e. the ones I’ve heard of). The disc that captured my attention is Matt Sargent – Separation Songs (CB0055 coldbluemusic.com), a set of 54 variations on selections from William Billings’ New England Psalm Singer. Composed between 2013 and 2018, Sargent has scored these four-voice hymn tunes, originally published in 1770, for two string quartets. On this recording the Eclipse Quartet accompanies and interacts with itself through overdubbing. Sargent says: “Throughout the piece, hymns tunes appear and reappear in ever-expanding loops of music passed between the quartets. Each time they return, the tunes filter through a ‘separation process’ whereby selected notes migrate from one quartet to the other. This process leaves breaks in the music that either remain silent or are filled in by stretching the durations of nearby notes, generating new rhythms and harmonies.” To my ears, the effect is like listening to a Renaissance consort of viols through a layer of gauze, or filtered by the mists of time, much like when ghostly strains of Schubert’s Death and the Maiden appear in George Crumb’s Black Angels. If I said you would need patience for Cooper’s protracted Stabat Mater, that is more than doubly the case for this 73-minute, one-track composition, but again, it rewards every moment of attention. I look forward to exploring the Cold Blue back catalogue, and to future releases.

Listen to 'Separation Songs' Now in the Listening Room

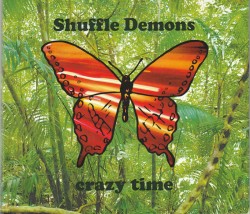

Well, all that listening to atmospheric and mist-shrouded ambience left me needing an injection of backbeat and rhythm, so when I found the latest from the Shuffle Demons in my inbox I knew the remedy was in hand. I’ll admit I may not be the ideal candidate to take on this review as it’s somewhat beyond my usual purview, but having spent some of my formative years in funky Queen St. W., I have fond memories of watching this outstanding (and outrageous) band playing on the streets of the neighbourhood. It came as a bit of a surprise to me that the Demons were still active some 35 years later, but it was a pleasant one indeed. Their ninth album Crazy Time (Stubby Records SRCD 1703 shuffledemons.com) features the classic three saxes and driving rhythm of bass and drums the Demons are known for. It includes two new members, Matt Lagan on tenor sax and bassist Mike Downes alongside stalwarts Richard Underhill, Kelly Jefferson and Stich Wynston, but in honour of their 35th anniversary, original members Mike Murley and Jim Vivian appear on five of the ten tracks. As in the past, hot instrumentals are interspersed with topical vocal tracks reminiscent of the classic Spadina Bus – be sure to check out the YouTube videos of that defining song – including the title track with its commentary on Ontario’s current leadership among other things: “We live in a crazy town, in a crazy world, in a crazy time.” All tunes were penned and arranged by Underhill with the exception of Jefferson’s smooth instrumental Even Demons Get the Blues and the retro rap vocal Have a Good One which Underhill co-wrote some years ago with interim Demons Eric St-Laurent, Mike Milligan and Farras Smith. The signature swinging unison horn choruses and individual solo takes are as strong as ever, and the infectious beat goes on. It’s great to find this iconic Canadian jazz institution alive and well, with no signs of aging or decay; long may the Shuffle Demons reign!

Well, all that listening to atmospheric and mist-shrouded ambience left me needing an injection of backbeat and rhythm, so when I found the latest from the Shuffle Demons in my inbox I knew the remedy was in hand. I’ll admit I may not be the ideal candidate to take on this review as it’s somewhat beyond my usual purview, but having spent some of my formative years in funky Queen St. W., I have fond memories of watching this outstanding (and outrageous) band playing on the streets of the neighbourhood. It came as a bit of a surprise to me that the Demons were still active some 35 years later, but it was a pleasant one indeed. Their ninth album Crazy Time (Stubby Records SRCD 1703 shuffledemons.com) features the classic three saxes and driving rhythm of bass and drums the Demons are known for. It includes two new members, Matt Lagan on tenor sax and bassist Mike Downes alongside stalwarts Richard Underhill, Kelly Jefferson and Stich Wynston, but in honour of their 35th anniversary, original members Mike Murley and Jim Vivian appear on five of the ten tracks. As in the past, hot instrumentals are interspersed with topical vocal tracks reminiscent of the classic Spadina Bus – be sure to check out the YouTube videos of that defining song – including the title track with its commentary on Ontario’s current leadership among other things: “We live in a crazy town, in a crazy world, in a crazy time.” All tunes were penned and arranged by Underhill with the exception of Jefferson’s smooth instrumental Even Demons Get the Blues and the retro rap vocal Have a Good One which Underhill co-wrote some years ago with interim Demons Eric St-Laurent, Mike Milligan and Farras Smith. The signature swinging unison horn choruses and individual solo takes are as strong as ever, and the infectious beat goes on. It’s great to find this iconic Canadian jazz institution alive and well, with no signs of aging or decay; long may the Shuffle Demons reign!

Listen to 'Crazy Time' Now in the Listening Room

We invite submissions. CDs, DVDs and comments should be sent to: DISCoveries, WholeNote Media Inc., The Centre for Social Innovation, 503 – 720 Bathurst St. Toronto ON M5S 2R4.