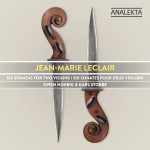

Violinists Gwen Hoebig and Karl Stobbe have been sitting together on the front desk of the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra for 20 years, and have been playing duets together for almost that long. A staple of their repertoire, the Six Sonatas for Two Violins by Jean-Marie Leclair is featured on a new CD from Analekta (AN 2 8786 analekta.com).

Violinists Gwen Hoebig and Karl Stobbe have been sitting together on the front desk of the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra for 20 years, and have been playing duets together for almost that long. A staple of their repertoire, the Six Sonatas for Two Violins by Jean-Marie Leclair is featured on a new CD from Analekta (AN 2 8786 analekta.com).

Leclair (1697-1764) was considered the father of French violin playing, merging the Italian influence he picked up while working for the ballet in Turin in his 20s with the French dance forms. These Op.3 Duos are known for their difficulty, but despite the need for technical mastery and virtuosity are never merely brilliant show pieces but works full of elegance and reserve, and of “lilting pastorals, graceful sarabandes and fiery jigs.”

Hoebig and Stobbe have technical mastery to spare, with a bright, clear sound and beautifully clean playing. The first and second violin parts are equally important here, with constant interplay and textural depth, and it’s virtually impossible to tell them apart.

Leclair had what the publicity release calls a tumultuous life, and was stabbed to death in front of the house he owned in a rather seedy area of Paris, possibly at the instigation of his former wife, who had been left penniless upon their divorce and who inherited his house and possessions, or by his nephew, an aspiring violinist angered at Leclair’s refusal to help advance his career. In the booklet notes Stobbe suggests that the nature of the duos – “the intimacy of two violins working together through tribulations and trials, romance, and violence” – may well reflect the circumstances of Leclair’s life, giving the performers a good starting point to explore the music’s character. His hope that these performances go beyond the technical challenges to give a sense of the man who created them is more than fulfilled in an outstanding CD.

Violinist Isabelle Faust and harpsichordist Kristian Bezuidenhout are in outstanding form in a 2CD set of J.S. Bach: Sonatas for Violin & Harpsichord (harmonia mundi 90225657).

Violinist Isabelle Faust and harpsichordist Kristian Bezuidenhout are in outstanding form in a 2CD set of J.S. Bach: Sonatas for Violin & Harpsichord (harmonia mundi 90225657).

These six works BWV 1014-1019 probably date from the Cöthen period of 1717-23, but Bach apparently continued to revisit and revise them throughout his life, suggesting that they were works that meant a great deal to him. From a historical perspective they form a crucial link between the Baroque trio sonata and the violin and piano sonatas of the Classical and Romantic periods, Bach treating the left and right hand keyboard parts as bass line and melodic voice respectively, with the violin interacting primarily with the melodic voice.

The performances here are quite superb, with a lovely balance between the instruments and a striking warmth and clarity. In his perceptive booklet notes Bezuidenhout offers the suggestion that the acquisition of a new double-manual harpsichord by Michael Mietke of Berlin at Cöthen in 1719 may well have provided the inspiration for Bach’s sudden keyboard innovations; there seem to be no other sources for this sudden departure from the standard trio sonata form.

The harpsichord used here, courtesy of Trevor Pinnock, is a modern John Phillips instrument modelled after a 1722 harpsichord by Johann Heinrich Grabner. Bezuidenhout notes that the sound “is both full… and wonderfully articulate,” the clarity between the registers ideal for the three-voice counterpoint so much at the heart of these sonatas. Faust plays a 1658 Jacob Stainer violin, which Bezuidenhout notes has the “necessary brilliance... but also a certain warmth and darkness of tone that is ideally suited to the more melancholy moments.”

All in all, it’s a wonderful set.

I didn’t know the playing of Tomas Cotik before last month’s outstanding Piazzolla Legacy CD, but his latest release, a simply beautiful 4CD set of the Complete Mozart 16 Sonatas for Violin and Piano with his regular partner Tao Lin (Centaur CRC 3619/20/21/22 centaurrecords.com), leaves me in no doubt as to what I must have been missing.

I didn’t know the playing of Tomas Cotik before last month’s outstanding Piazzolla Legacy CD, but his latest release, a simply beautiful 4CD set of the Complete Mozart 16 Sonatas for Violin and Piano with his regular partner Tao Lin (Centaur CRC 3619/20/21/22 centaurrecords.com), leaves me in no doubt as to what I must have been missing.

This set – Cotik’s 14th issue – does not include the “juvenile” sonatas for keyboard and violin from 1763-66, where the violin rarely does little more than conform to the keyboard right hand, but presents the 16 sonatas written in the period 1778-88: the six sonatas K301-306 published in Paris in late 1778 and known as the Kurfürstin or Palatine Sonatas; the six sonatas K296 and K376-380 published by Artaria in Vienna in late 1781 and dedicated to Mozart’s pupil Josepha Aurnhammer; and the later Viennese sonatas K454 (1784), K481 (1785), K526 (1787) and K547 (1788).

In the accompanying publicity material, Cotik describes the lengths to which he and Lin had to go to reduce and eliminate the extraneous noises from the Fort Lauderdale church they had chosen as the recording venue. The resulting full-movement takes more than justify their efforts: the sound quality and balance are excellent, with the violin never too far forward but never overshadowed by the piano either. Both performers play with a resonant, clear and warm tone, and dynamics, phrasing and tempi are all perfectly judged.

Cotik readily admits to having always loved Mozart’s music, and calls his recordings of these sonatas a milestone in his musical life. It’s a sentiment that is clearly evident in every single track of this exemplary set.

This really has been a tremendous month for violin CDs. The American violinist Rachel Barton Pine marks her 36th recording and her fourth album for the Avie label with the Elgar and Bruch Violin Concertos, with the BBC Symphony Orchestra conducted by Andrew Litton (AV2375 avie-records.com).

This really has been a tremendous month for violin CDs. The American violinist Rachel Barton Pine marks her 36th recording and her fourth album for the Avie label with the Elgar and Bruch Violin Concertos, with the BBC Symphony Orchestra conducted by Andrew Litton (AV2375 avie-records.com).

Pine calls the project an “indulgence in Romanticism,” being the first time that the shortest of the regular repertoire Romantic concertos – the Bruch Violin Concerto No.1 in G Minor Op.26 – has been recorded together with the longest – Elgar’s Violin Concerto in B Minor Op.61. Although they have little in common from a historical perspective, Pine has long thought of them together because each work reminds her of the warm, rich and soulful sound she looks for in the other.

The Bruch was the first Romantic concerto that Pine learned (at the age of eight!) and the Elgar was one of the last, its highly technical challenges, numerous tempo changes and sheer length making it particularly difficult to learn (James Ehnes expressed the same concerns prior to his recording with Andrew Davis in 2007). The original conductor for this project was Sir Neville Marriner, who conducted the Academy of St Martin in the Fields on Pine’s critically acclaimed Avie album of the complete Mozart violin concertos, but he passed away shortly after Pine visited London to play and discuss the Elgar with him. It was a sad loss, for Marriner’s teacher was Billy Reed who, as the young concertmaster of the London Symphony Orchestra, had helped Elgar with the solo violin part. What would Sir Neville have brought to his first recording of the work, one wonders.

Still, Litton does an excellent job with a concerto that can be difficult to hold together, his accompaniment having a quite different sound at times – not exactly lighter or smaller, but perhaps not as serious as some, with a great deal of sensitivity and attention to detail. There is certainly no tendency toward Elgarian pomp or Edwardian stuffiness that can sometimes make the concerto sound a bit laboured or meandering in less experienced hands.

Pine’s playing in the Elgar is thoughtful and unerringly accurate with no hint of mere virtuosity, although there is perhaps less of a feel of sweeping grandeur than in some other performances. Much the same can be said of the Bruch, where again the foremost impression is one of intelligence and sensitivity in the playing rather than unabashed Romantic passion. It supports Marriner’s observation of Pine’s playing in the Mozart set, when he said “...there is no utter embellishment, everything is there for a purpose, and musically speaking, it makes such good sense.”

Dedicated “to the memory of a musical hero and generous friend, Sir Neville Marriner,” the CD is an excellent addition to Pine’s impressive discography.

There’s playing of the utmost warmth and sensitivity on Antonín Dvořák: String Quintet Op.97 & String Sextet Op.48, featuring the Jerusalem Quartet with violist Veronika Hagen and, in the sextet, cellist Gary Hoffman (harmonia mundi 902320).

There’s playing of the utmost warmth and sensitivity on Antonín Dvořák: String Quintet Op.97 & String Sextet Op.48, featuring the Jerusalem Quartet with violist Veronika Hagen and, in the sextet, cellist Gary Hoffman (harmonia mundi 902320).

The Sextet in A Major was written in 1878 and was clearly modelled on the two string sextets of Brahms, who commented many years later on the “wonderful invention, freshness and beauty of sound” in the work. It was Brahms who had recommended Dvořák to his own publisher Simrock in 1877, and there is certainly more than a hint of the German Romantic tradition here as well as the inevitable Slavonic folk influence. The performance has effusiveness and passion, with a lovely Dumka movement and a terrific Finale.

There’s no less passionate and committed playing in the Quintet in E-flat Major, which simply abounds in lyrical warmth and beauty. It was written, along with the “American” string quartet, in the Czech community of Spillville, Iowa in the summer of 1893 during Dvořák’s stay in the United States.

These are simply ravishing performances, with Alexander Pavlovsky’s gorgeous first violin playing leading the way and setting a standard that the other performers have no problem matching.

The Russian pianist, composer and teacher Alla Elana Cohen came to the United States in 1989 and is currently a professor at Berklee College of Music in Boston. Jupiter Duo is the title of a new CD of her music, as well as the name of the performing duo of cellist Sebastian Bäverstam and Cohen herself on piano (Ravello Records RR7978 ravellorecords.com).

The Russian pianist, composer and teacher Alla Elana Cohen came to the United States in 1989 and is currently a professor at Berklee College of Music in Boston. Jupiter Duo is the title of a new CD of her music, as well as the name of the performing duo of cellist Sebastian Bäverstam and Cohen herself on piano (Ravello Records RR7978 ravellorecords.com).

Cohen discovered Bäverstam, now 29, when he was barely 12 years old, and the first work of hers that they performed then, the Book of Prayers Volume 1, Series 7, opens the CD. All subsequent Cohen cello works were written for Bäverstam, and there are three other cello and piano works here: Third Vigil, an arrangement (which Cohen prefers) of her Concerto for Cello and Orchestra; Querying the Silence Volume 1, Series 2; and Book of Prayers Volume 2, Series 4, which closes the CD.

Sephardic Romancero Series 2 is a challenging solo work ably handled by Bäverstam, although Cohen’s statement that “for anybody else it will be almost impossible to play this piece” says little for her awareness of contemporary world-class cellists. Cohen also contributes two works for solo piano: Three Film Noir Pieces and Spiral Staircases.

It’s tough music to get a handle on, with little melodic content, a lot of thick, dense texture in the predominantly discordant piano writing and a good deal of large, heavy chords spread across the entire keyboard range. From the cello perspective Bäverstam handles all the technical challenges with ease; his lower tone in particular is beautifully rich.

Of the final work on the CD, Cohen says that it is one of the rare-for-her compositions “in which lighter colours prevail. It is also the most ‘consonant’ by sonority, at times even quasi-tonal.” That should give you some idea of the music on the rest of the disc, which generally seems to be tough, abrasive and frequently decidedly dark.

Haydn – Symphonies 26 & 86; Mozart – Violin Concerto No.3

Haydn – Symphonies 26 & 86; Mozart – Violin Concerto No.3