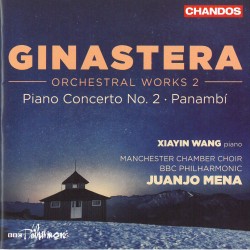

Ginastera Orchestral Works 2: Panambi; Piano Concerto No.2 - Xiayin Wang; Manchester Chamber Choir; BBC Philharmonic; Juanjo Mena

Ginastera Orchestral Works 2 – Panambi; Piano Concerto No.2

Ginastera Orchestral Works 2 – Panambi; Piano Concerto No.2

Xiayin Wang; Manchester Chamber Choir; BBC Philharmonic; Juanjo Mena

Chandos CHAN 10923

Continuing a 2016 series celebrating the centennial of Argentinian master Alberto Ginastera’s birth, this disc offers an intriguing contrast of compositions from his early and late periods. Beginning with the latter, Xiayin Wang’s elegant and sonorous performance of the Second Piano Concerto (1972) will be a surprise for anyone who associates the composer with pianistic bombast. Her crisp, even touch in both the perpetual motion, repeated-note scherzo and the prestissimo triplet finale is remarkable, yet so is her balance of complex chords and gradual pacing in the tread-like build of the slow movement to a crisis point. The first movement is the most dissonant and complex. Succeeding movements are more accessible; textures and sounds fascinate throughout. Altogether, this work is a major statement of artistic freedom and of identification with both classical and contemporary music for the composer, who had recently moved to Switzerland from the darkening situation in his homeland.

Panambi (1934-37), subtitled Choreographic Legend in One Act, is Ginastera’s Op.1. It is a precocious work from his folkloric years, one which also includes modern tendencies. Notable are the composer’s varied percussion writing and his seeking out of innovative low-register combinations. Rather than dwell on obvious influences from early 20th-century Paris, I would like to emphasize his successful evocation though imagery and sound of the Argentinian pampas, suggesting feelings associated with nature and the past. The BBC Philharmonic led by Juanjo Mena play with verve and sensitivity throughout.