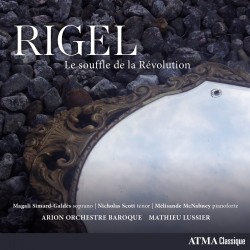

Henri-Joseph Rigel and the Winds of Revolution - Magali Simard-Galdes; Nicholas Scott; Melisande McNabney; Arion Baroque Orchestra; Mathieu Lussier

Henri-Joseph Rigel and the Winds of Revolution

Henri-Joseph Rigel and the Winds of Revolution

Magali Simard-Galdes; Nicholas Scott; Melisande McNabney; Arion Baroque Orchestra; Mathieu Lussier

ATMA ACD2 2828 (atmaclassique.com/en/product/rigel-and-the-winds-of-revolution)

The name Henri-Joseph Rigel is probably an unfamiliar one today, but during his lifetime he was a highly esteemed composer and conductor in 18th century France. Born Heinrich-Joseph Riegel in Wertheim am Main in 1741, he moved to Paris in 1767 where he soon earned a reputation in musical circles for his harpsichord pieces, symphonies and concertos, in addition to 14 operas.

It seems particularly appropriate that the Montreal-based Arion Ensemble Baroque has chosen to uncover the music of this deserving but largely forgotten composer on this splendid recording titled Le Souffle de la Révolution under the direction of Mathieu Lussier. Collaborating with the Centre de Musique Baroque de Versailles, the group presents a program not dissimilar to a concert of the period in its attractive mix of orchestral works, concertos, arias and duets.

Leading off the program are the overture and three arias from Rigel’s 1781 pastoral comedy Blanche et Vermeille, the vocal pieces artfully performed by Québec soprano Magali Simard-Galdès and British-born tenor Nicholas Scott. The singers both do justice to this unfamiliar repertoire and return later in the program for arias from Rigel’s revolutionary period operas Pauline et Henri and Alix de Beaucaire.

The Symphony Op.12 No.2 and the Fortepiano Concerto in F Major are fine examples of the Viennese classical style – do I detect echoes of Haydn? The concerto features soloist Mélisande McNabney who offers a stylish performance and provides a convincing cadenza while under Lussier’s competent baton, Arion proves a solid and sensitive partner.

Like finding a treasure in an attic, the discovery of this hitherto unknown music is a delight and a big merci to the AOB not only for some fine music making, but for rescuing it from oblivion.