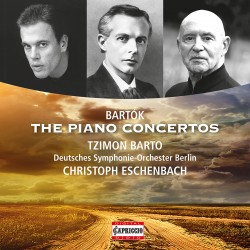

Béla Bartók - The Piano Concertos

Béla Bartók - The Piano Concertos

Tzimon Barto; Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin; Christoph Eschenbach

Capriccio C5537 (naxos.com/CatalogueDetail/?id=C5537)

If your previous impressions of Bartók’s three piano concertos have been of predominantly percussive music, hammered at aggressively, this new recording will have you hearing the music afresh. In the promotional material for the album, pianist Tzimon Barto states, “Even Bartók needs a supple touch. If you bang away at it, without rhythmical buoyancy, of course it will become tedious.” Here, Barto is joined in the concertos by the Deutches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin conducted by Christoph Eschenbach.

For an example of the dividends this approach pays, listen to the beginning of the first concerto. In place of the usual martellato repeated A’s, the opening grows gradually and is remarkably atmospheric. Full advantage is taken of any calm moments here and in the second concerto, creating passages of rapt stillness which in other performances go by unnoticed. There is a notable softening of the edges as a result of this “supple” and “buoyant” approach. Perhaps due to the recording balance, in which the piano is recessed into the orchestra, Bartók’s carefully indicated and often sudden dynamic contrasts can, however, seem downplayed. True fortissimos are rare, even in the biggest climaxes.

As another notable instance of Barto’s approach, take the opening of the third concerto, by far the most frequently performed of the three. The piano’s opening melody is played so freely and flexibly that it seems to float magically above the gentle string accompaniment. On the other hand, Bartók’s rhythms are nevertheless notated precisely, and reflect the folksongs and dances which are such an important ingredient in his musical language. Additionally, the first movement’s tempo is so slow (two minutes longer than in many other recordings) that the music risks losing forward momentum. These performances may shun percussive aggression, but they also downplay the rhythmic drive and precision that make Bartók’s music so unique. The orchestra, with some particularly fine contributions from the winds, sounds uneasy with the liberties of tempo and rubato, and ensemble suffers in several sections.

Barto is to be commended for reminding us of the lyricism and delicacy inherent in Bartók’s music (listen to the composer’s own recordings of his piano works to hear this), but the extremes to which Barto goes to emphasize these elements may not be to everyone’s taste.