Let us start our story in the present day in the person of Toronto pianist Mary Kenedi. To commemorate the 60th anniversary of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, as well as the 135th anniversary of the birth of Hungary’s pre-eminent 20th-century composer Béla Bartók, she has organized two November concerts titled A Bridge to the Future. The first concert on November 17 is at Trinity-St. Paul’s Centre, while the second is at the Canadian Museum of History, Gatineau, Quebec on November 29. As for the title, A Bridge to the Future, Kenedi explains that “the title symbolizes the hopefulness of immigrants from Hungary who travelled to a new continent, replacing their country of birth with a new one that offered freedom and democracy.”

Let us start our story in the present day in the person of Toronto pianist Mary Kenedi. To commemorate the 60th anniversary of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, as well as the 135th anniversary of the birth of Hungary’s pre-eminent 20th-century composer Béla Bartók, she has organized two November concerts titled A Bridge to the Future. The first concert on November 17 is at Trinity-St. Paul’s Centre, while the second is at the Canadian Museum of History, Gatineau, Quebec on November 29. As for the title, A Bridge to the Future, Kenedi explains that “the title symbolizes the hopefulness of immigrants from Hungary who travelled to a new continent, replacing their country of birth with a new one that offered freedom and democracy.”

She was one of them. And so was I.

The 1956 Hungarian Revolution - some call it the Uprising - began on the afternoon of October 23 as a crowd of at least 20,000 demonstrators assembled in central Budapest. Starting as a peaceful demonstration it quickly turned very bloody indeed. I had just turned six in the Western Hungarian city of Szombathely.

Descriptions drawn partly from a 1957 UN General Assembly report paint a complicated picture of the compelling events which led up to and then followed it. Here’s a much-simplified snapshot.

Students and writers joined forces to voice their grievances levelled against the hardline Stalinist government of the Hungarian People’s Republic. The crowd’s initial goal was the public square adjacent to the statue of József Bem, a 19th-century military figure, a hero for both Poles and Hungarians. There, Péter Veres, the president of the Hungarian Writers’ Union, read a 16-point manifesto to the crowd, challenging the current national regime on several fronts.

By the evening of October 23 the crowds swelled by a factor of ten when the students joined other Budapesters in the large parliament-building plaza on the opposite shore of the Danube. One group of demonstrators in the city’s Hero Square toppled and broke up the imposing bronze statue of Stalin, a potent symbol of oppression and occupation. They left only its metal boots in which the Hungarian flag was planted. A larger group was fired upon at the national radio station by the State Security Police (ÁVO) resulting in numerous demonstrator deaths.

That October day’s momentous events marked the start of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution. As its news spread, further demonstrations and armed conflict erupted in the capital and flashed throughout the country. Within days the existing government fell and a new one was formed. Within the week Soviet troops withdrew just outside the country’s borders. For a few heady days a democratic and independent country seemed within the grasp, at least in the imagination of many hopeful Hungarians.

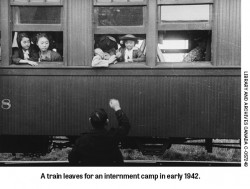

Beginning on November 3, however, multiple Soviet armed divisions began their return to Budapest and other major Hungarian centres with the aim of swiftly destroying the Revolution and installing a government under Moscow’s control. Armed Hungarian resistance was extirpated by November 10. Records indicate that over 2,500 Hungarians and 700 Soviet troops were killed in the conflict, and 200,000 Hungarians subsequently fled the county as refugees. (Most fled through Austria, as did my family. It’s a route retraced by recent Syrian and other refugees.)

This fall marks the 60th anniversary of those difficult events. For decades public discussion about the Revolution was suppressed in Hungary. October 23, the date marking the start of the 1956 Revolution, is a national holiday today in Hungary.

Kenedi’s motivation for organizing the concerts is multi-layered, musical and social. Her overall musical aim, she says, is “to educate people about the high quality of Hungarian compositions, and to help audiences get past the knee-jerk reaction of fear on hearing the names of 20th century composers.”

But her personal background also plays strongly into things: “I also hope to inspire the descendants of the 1956 immigrants to keep in touch with their rich cultural heritage,” she says, using her own life experience to illustrate her point. “I emigrated from Hungary to Canada with my family…after the Hungarian Uprising. In Toronto I studied piano with Mona Bates and Pierre Souvairan. Then I returned to Hungary where I worked directly with students of Béla Bartók, followed by a year of studies at the Liszt Academy,” she adds. “Returning to Toronto, I received my master’s degree in music at the University of Toronto and made my New York recital debut at Carnegie Hall.”

The musical exodus: Just like everyone else, Hungarian musicians were caught up in the post-Revolution maelstrom. Like his composer friend and colleague György Ligeti, the multiple-award winning Hungarian composer of contemporary classical music György Kurtág (b. 1926) also fled his homeland after the sad outcome of the 1956 Revolution became evident.

The musical exodus: Just like everyone else, Hungarian musicians were caught up in the post-Revolution maelstrom. Like his composer friend and colleague György Ligeti, the multiple-award winning Hungarian composer of contemporary classical music György Kurtág (b. 1926) also fled his homeland after the sad outcome of the 1956 Revolution became evident.

Both in terms of general impact and Canada’s musical community the events of 1956 had immediate, as well as long-term, resonances here too. In 2010 the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of the Canadian government declared the “Historical Significance of the Refugees of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution,” stating that more than 37,500 Hungarians were admitted into the county during the period between late 1956 and the end of 1957, observing further that “Hungarian refugees themselves, generally young and highly qualified when they arrived, contributed significantly to Canadian society, particularly to its cultural diversity and to the national economy by contributing their skills to the country’s workforce.…This has in turn contributed significantly to the creation of an open, tolerant and culturally diverse society, which remains a source of pride to us all.”

Putting those 1950s immigration figures into the current context, the Canada 2011 Census indicates that 316,765 Canadians claim Hungarian ancestry. Internationally, Canada ranks fourth among the countries of the Hungarian diaspora.

The tsumani of immigration following on the heels of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, my own family among them, included many musicians, music teachers and university students. Settling mainly in the largest Canadian cities, in a few years they had begun to establish themselves musically in their new country.

The celebrated Hungarian composer, ethnomusicologist and music educator Zoltán Kodály visited Canada in 1964, and again in 1966, when he gave the MacMillan Lectures at the University of Toronto, where he was also awarded an honorary doctorate. His visits were facilitated by his former student George Zaduban (1931-2003), a music teacher, conductor, organist and composer-arranger who, in 1960 had founded a choir mainly comprised of recently arrived Hungarians in Toronto, the Kodály Chorus. A folk-dance group was added soon afterwards and thus the Kodály Ensemble was born. Periodically the group would be supplemented by an orchestra, and it mounted ambitious performances involving over a hundred performers in major Toronto venues. As a teenager in the late 1960s I sang tenor with the Chorus for a season or two, including, as I recall, singing in the Kodály Chorus on its tour to Cleveland, Ohio.

The Hungarian music educator and composer, Thomas LeGrady, also immigrated to Canada in 1956, initially settling in Montreal where he taught solfège and orchestration at Loyola College and elsewhere. Another Kodály student, the conductor, composer, pianist and teacher Tibor Polgar (1907-1993) made Toronto his home. He taught for years at the University of Toronto and at York University while scoring feature and documentary films, plus CBC radio and TV soundtracks, often employing Hungarian idioms in his compositions.

And beyond these examples of first generation 1956 Hungarian emigrants who continued their careers in Canada, the influence of the events of 1956 continues to echo among second generation Canadian musicians as well. A good example is the multi-Grammy Award-winning songwriter-singer Alanis Morissette (b. 1974). Her father is French Canadian while her mother fled Hungary with her family after the 1956 Revolution. Another is Kati Ilona Agócs (b. 1975) the successful midcareer Canadian composer of contemporary classical music and faculty member at the New England Conservatory of Music. Agócs grew up in Southwestern Ontario, where her Hungarian father eventually settled after leaving Hungary in the wake of the 1956 events.

As for Mary Kenedi, her sense of mission and allegiance has broadened over the years into an avid advocacy of 20th-century Canadian composers as well as of Hungarians; in 1993 Kenedi organized and performed an 80th birthday concert for the eminent Toronto composer John Weinzweig (1913-2006). It was nationally broadcast on CBC radio and released as a Centrediscs CD.

Pursuing a career-long commitment to the music of Bartók, Kenedi notes with enthusiasm that “one of my most memorable concerts was the solo recital I gave at the Bartók Memorial House in Budapest. Last November I performed a program at the Hungarian Embassy in Ottawa to commemorate the 70th anniversary of Bartók’s death. As for albums, I’ve issued two recordings of Bartók’s music, [Zoltan] Kodály’s complete piano works, in addition to three all-Canadian CDs.”

Reflecting the contribution: I asked Kenedi about the contributions of Hungarian musicians who made Canada their home in the wake of the 1956 Revolution. She was quick with her reply. “For such a small country, Hungary has produced a multitude of talented people in all walks of life, but to be immodest, particularly in the arts. Composers, instrumental and vocal soloists, chamber musicians and orchestral players are all represented. Check members of any orchestra and Hungarian names keep popping up. The vitality and wonderful training of these artists who came to Canada made an enormous difference in our musical landscape.”

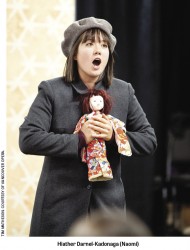

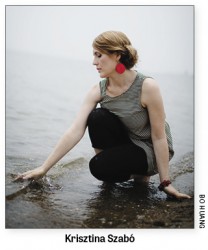

The November “Bridge to the Future” concert program is true to its name: “It will have three Kodály songs sung by wonderful mezzo-soprano and actress Krisztina Szabó. She’s a no-brainer since I really respect her talent…as well as her sense of humour! We’ll have Dohnányi’s Trio Op. 10, Kodály’s Piano Sonata Op. 4 and his very significant Cello Sonata Op. 8, a work full of references to Hungarian folk music. I am playing Liszt’s Les jeux d’eaux à la Villa d’Este, and of course some Bartók: Three Hungarian Folksongs from the Csik District, Fifteen Hungarian Peasant Songs, and Romanian Dance Op. 8a among several other of his works for piano solo. Operetta arias by Hungarian composers Lehár and Kálmán will provide a lighter touch to close our evening.”

The November “Bridge to the Future” concert program is true to its name: “It will have three Kodály songs sung by wonderful mezzo-soprano and actress Krisztina Szabó. She’s a no-brainer since I really respect her talent…as well as her sense of humour! We’ll have Dohnányi’s Trio Op. 10, Kodály’s Piano Sonata Op. 4 and his very significant Cello Sonata Op. 8, a work full of references to Hungarian folk music. I am playing Liszt’s Les jeux d’eaux à la Villa d’Este, and of course some Bartók: Three Hungarian Folksongs from the Csik District, Fifteen Hungarian Peasant Songs, and Romanian Dance Op. 8a among several other of his works for piano solo. Operetta arias by Hungarian composers Lehár and Kálmán will provide a lighter touch to close our evening.”

Will these concerts be of interest to non-Hungarian Canadians? I ask. Kenedi responds by talking about the innate power and universality of folk music: “While it’s a broad generalization, [I feel] folk music is based on the everyday lives…of ethnic groups and thus communicates on an even more gut level than through-composed music does. It attracts the sympathy and empathy of listeners, even though they may not share those same ethnic roots.”

As for her own future plans, they speak to a balanced identity. “I’m working on arranging performances of two pieces I have commissioned, a choral fantasy by Abigail Richardson, and a concerto for piano, percussion and strings by Kevin Lau, both younger-generation Canadian composers. I do get sidetracked into works that do not fit into either Hungarian or Canadian composer categories. An example is my 2013 Naxos CD of the chamber music of Nino Rota. I enjoy performing less-known repertoire.”

Her hope is that these concerts will provide an opportunity for others to look back with similar clarity, in order to move confidently ahead.

Andrew Timar is a Toronto musician and music writer. He can be contacted at worldmusic@thewholenote.com.

![]()

For the last 25 years, my favourite day of the year has been the last Sunday before Christmas. That is the day when, along with thousands of other choral enthusiasts, and conducted by George Frideric Handel himself, I get to sing the wondrous choruses of the Messiah.

For the last 25 years, my favourite day of the year has been the last Sunday before Christmas. That is the day when, along with thousands of other choral enthusiasts, and conducted by George Frideric Handel himself, I get to sing the wondrous choruses of the Messiah.