There’s an outstanding new recording of the quite remarkable Mystery Sonatas, or Rosary Sonatas of Heinrich Ignaz Franz von Biber, violinist Alan Choo the exceptional soloist with Apollo’s Fire, under the direction of Jeanette Sorrell at the harpsichord (Avie AV2656 avie-records.com).

There’s an outstanding new recording of the quite remarkable Mystery Sonatas, or Rosary Sonatas of Heinrich Ignaz Franz von Biber, violinist Alan Choo the exceptional soloist with Apollo’s Fire, under the direction of Jeanette Sorrell at the harpsichord (Avie AV2656 avie-records.com).

Believed to have been written in the 1670s and never published – the sole source is the manuscript dating from around 1676 – the 15 sonatas follow events in the lives of Jesus and the Virgin Mary, known in Catholic tradition as the Mysteries of the Rosary. A monumental solo, Passacaglia in G Minor, completes the set.

What makes the work so remarkable is the unprecedented and unsurpassed use of scordatura – the re-tuning of the violin strings – with all 15 sonatas requiring different tunings and the resulting use of multiple violins, Choo using six here.

The manuscript gives no indication regarding accompaniment, with Sorrell choosing to use various combinations of continuo instruments to add colour and variety to the individual sonatas.

Excellent booklet notes, with full tuning details and reproductions of the copper engravings Biber placed at the start of each sonata in the manuscript, add to a superb release.

The Armenian violinist Sergey Khachatryan is simply superb on Ysaÿe VI Sonatas, the set of 6 Sonatas for solo violin Op.27 by the Belgian violinist and composer Eugene Ysaÿe (naïve V 5451 arkivmusic.com/products/ysaye-sergey-khachatryan).

The Armenian violinist Sergey Khachatryan is simply superb on Ysaÿe VI Sonatas, the set of 6 Sonatas for solo violin Op.27 by the Belgian violinist and composer Eugene Ysaÿe (naïve V 5451 arkivmusic.com/products/ysaye-sergey-khachatryan).

After hearing Joseph Szigeti play Bach’s Sonata No.1 in G Minor in early 1923, Ysaÿe decided to compose his own tribute to Bach, reflecting current musical language and violin technique while also incorporating elements of Szigeti’s style. By July he had written a further five, each dedicated to and depicting a different violinist: Jacques Thibaud; Georges Enescu; Fritz Kreisler; Mathieu Crickboom; and Manuel Quiroga.

What makes this release extra special, though, is the fact that it marks the first recording of the sonatas on Ysaÿe’s 1740 Guarneri del Gesù violin, on loan from the Nippon Music Foundation; its sumptuous tone in such supremely talented hands fully exploits the instrument’s wide range of tonal colour.

Canadian violinist Karl Stobbe presents works for solo violin by Ysaÿe, J.S. Bach & Paganini in a digital release that is part of a six-album series based on the Bach Sonatas & Partitas (Leaf Music LM294 leaf-music.ca).

Canadian violinist Karl Stobbe presents works for solo violin by Ysaÿe, J.S. Bach & Paganini in a digital release that is part of a six-album series based on the Bach Sonatas & Partitas (Leaf Music LM294 leaf-music.ca).

The Bach work here is the Partita No.1 in B Minor, BWV1002, with Ysaÿe’s Sonata in E Minor, Op.27 No.4 (dedicated to Fritz Kreisler) opening the recital and three of Paganini’s 24 Caprices Op.1 – No.9 in E Major, No.17 in E-flat Major and No.24 in A Minor – closing it. There is a hidden connection here: Kreisler apparently had a special affinity for this particular Bach Partita, and also arranged the Paganini Caprices for violin and piano.

Technical difficulties don’t seem to present any challenge for Stobbe, who handles everything with ease with his 1806 Nicolas Lupot violin and 1790 François Xavier Tourte bow.

Ukrainian-American violinist Solomiya Ivakhiv continues her mission to share the music of her home country with Ukrainian Masters, a new CD featuring 20th-century sonatas by three major figures in Ukrainian classical music. Steven Beck is the pianist (Naxos 8.579146 naxos.com/CatalogueDetail/?id=8.579146).

Ukrainian-American violinist Solomiya Ivakhiv continues her mission to share the music of her home country with Ukrainian Masters, a new CD featuring 20th-century sonatas by three major figures in Ukrainian classical music. Steven Beck is the pianist (Naxos 8.579146 naxos.com/CatalogueDetail/?id=8.579146).

The world-premiere recording of the1927 Violin Sonata in A Minor, Op.18 by Viktor Kosenko (1896-1938) is quite lovely, a lush, immediately accessible work beautifully played. The 1991 Violin Sonata No.2 by Myroslav Skoryk (1938-2020) with its “pointed allusions to Beethoven, Prokofiev and Gershwin” is another winner, with more fine playing.

Ivakhiv only recently discovered the music of Sergei Bortkiewicz (1877-1952), which was banned in the Soviet Union after he fled Ukraine in 1919. His Violin Sonata in G Minor, Op.26 was written in 1922 in Germany, and finds his mature musical language “at its most vivid and directly communicative.”

On The Night Shall Break violinist Hanna Hurwitz, joined by cellist Colin Stokes and pianist Daniel Pesca goes back 100 years to find neglected gems and present them alongside established works (Neuma Records 198 neumarecords.org).

On The Night Shall Break violinist Hanna Hurwitz, joined by cellist Colin Stokes and pianist Daniel Pesca goes back 100 years to find neglected gems and present them alongside established works (Neuma Records 198 neumarecords.org).

Florence Price’s attractive Fantasie No.1 for Violin and Piano from 1933 and Rebecca Clarke’s 1921 Piano Trio both produce top-level playing, and the standard never drops through the very brief (four movements, each less than two minutes) 1924 Sonatina for Violin and Piano by Carlos Chávez and particularly through the established works: Messiaen’s Thème et Variations pour Violon et Piano from 1932 and the terrific Duo No.1 for Violin and Cello by Bohuslav Martinů.

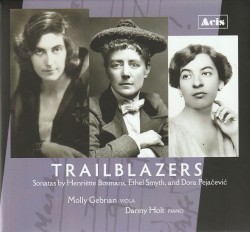

Violist Molly Gebrian discovered the works she plays on Trailblazers several years ago when listening to music online, YouTube’s auto-play feature kicked in to play cello sonatas by Dora Pejačević (1885-1923), Henriëtte Bosmans (1895-1952) and Ethyl Smyth (1858-1944). Gebrian knew immediately that these were sonatas she wanted to play, and her effective transcriptions for viola and piano are presented here. Danny Holt is the pianist (Acis APL54162 acisproductions.com).

Violist Molly Gebrian discovered the works she plays on Trailblazers several years ago when listening to music online, YouTube’s auto-play feature kicked in to play cello sonatas by Dora Pejačević (1885-1923), Henriëtte Bosmans (1895-1952) and Ethyl Smyth (1858-1944). Gebrian knew immediately that these were sonatas she wanted to play, and her effective transcriptions for viola and piano are presented here. Danny Holt is the pianist (Acis APL54162 acisproductions.com).

All three composers broke new ground by defying social expectations of their times. The Dutch Bosmans was a concert pianist as well as a composer; her Sonata in A Minor is from 1919. Dame Ethyl Smyth’s essentially Romantic Sonata in A Minor, Op.5 is from 1887, and the Croatian Pejačević’s Sonata in E Minor, Op.35 from 1913.

Gebrian is a superb player, strong and full-toned. Ably supported by Holt, she gets to the heart of these exceptional works in stellar performances.

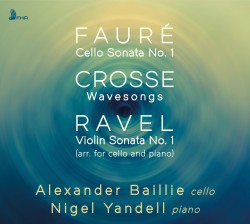

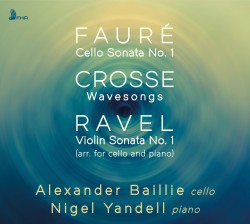

Cellist Alexander Baillie and pianist Nigel Yandell are in fine form on the new CD Fauré, Crosse and Ravel – Works for Cello & Piano (First Hand Records FHR152 firsthandrecords.com).

Cellist Alexander Baillie and pianist Nigel Yandell are in fine form on the new CD Fauré, Crosse and Ravel – Works for Cello & Piano (First Hand Records FHR152 firsthandrecords.com).

The disc opens with a lovely performance of Fauré’s Cello Sonata No.1 in D Minor, Op.109 from 1917 and ends with an effective transcription of Ravel’s early Violin Sonata No.1 in A Minor, Op.posth. M.12 from 1897. The heart of the CD, both physically and musically is the 1983 Wavesongs by the English composer Gordon Crosse, who died in 2021. Written for Baillie, it’s described as a 22-minute tone poem, a single-movement work with numerous sub-sections with titles like Sea Shanty, Troubled Waves, Storm, Cruel Sea, Tempest and Lost at Sea. This recording uses a newly revised performing edition resulting from Yandell’s partnership with Baillie and is dedicated to Crosse’s memory.

It’s a striking work and a notable addition to the contemporary cello repertoire, more than justifying the description as “a modern masterpiece” in the press release.

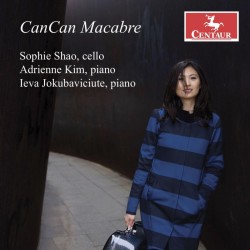

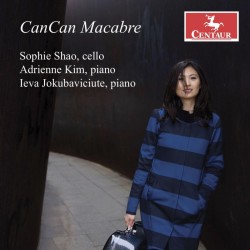

There are another two contemporary cello works on CanCan Macabre, with the American cellist Sophie Shao playing music by Couperin, Debussy, Herschel Garfein, Thomas Adès and Chopin. Adrienne Kim is the pianist in all but the Couperin and Chopin, where the pianist is Ieva Jokubaviciute (Centaur CRC4052 centaurrecords.com).

There are another two contemporary cello works on CanCan Macabre, with the American cellist Sophie Shao playing music by Couperin, Debussy, Herschel Garfein, Thomas Adès and Chopin. Adrienne Kim is the pianist in all but the Couperin and Chopin, where the pianist is Ieva Jokubaviciute (Centaur CRC4052 centaurrecords.com).

Couperin’s five Pièces en concert in the 1924 arrangement by Paul Bazelaire and Debussy’s 1915 Cello Sonata in D Minor open the disc, with the Largo from Chopin’s Cello Sonata in G Minor, Op.65 closing it. In between are the two contemporary works. Garfein’s The Layers, commissioned by and written for Shao, was inspired by the poem by former U.S. poet laureate Stanley Kunitz, its three sections reflecting central images in the poem.

Adès’ Lieux retrouvés was written in 2009 for Steven Isserlis, its final movement, La ville – cancan macabre providing the title for a high-quality CD.

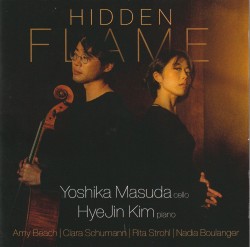

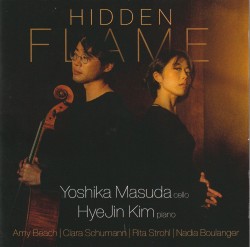

Hidden Flame, the new CD from cellist Yoshika Masuda and pianist HyeJin Kim features compositions by women presented simply as “masterpieces by truly great composers” (Avie AV2653 avie-records.com).

Hidden Flame, the new CD from cellist Yoshika Masuda and pianist HyeJin Kim features compositions by women presented simply as “masterpieces by truly great composers” (Avie AV2653 avie-records.com).

Amy Beach’s Romance Op.23 and Clara Schumann’s 3 Romanzen Op.22, both originally for violin and piano, provide a gorgeous opening with a full, rich cello sound across the entire range. The major work here is the lengthy (almost 40 minutes) 1892 Great Dramatic Sonata “Titus et Bérénice” by the French composer Rita Strohl (1865-1941), a little-known work that will repay repeated hearings.

Rena Ismail’s one word makes a world is a world-premiere recording; based on the third movement cello solo from her 2013 String Quartet, it was written for Masuda. Nadia Boulanger’s 3 Pieces for Cello and Piano are delightful, but the final track – the Sicilienne attributed to Maria Theresia Paradis – hardly qualifies as a masterpiece by a great composer; indeed, current research suggests that the composer was probably the violinist Samuel Dushkin.

No matter, for it closes a fine CD full of excellent playing.

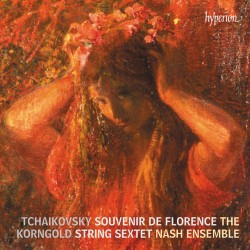

If you want to hear some superb string ensemble playing then look no further than Tchaikovsky & Korngold: String Sextets, the new release from the Nash Ensemble (Hyperion CDA68406 hyperion-records.co.uk/dc.asp?dc=D_CDA68406).

If you want to hear some superb string ensemble playing then look no further than Tchaikovsky & Korngold: String Sextets, the new release from the Nash Ensemble (Hyperion CDA68406 hyperion-records.co.uk/dc.asp?dc=D_CDA68406).

Although only written some 25 years apart, the two works are from opposite ends of their composers’ lives: Tchaikovsky’s Sextet in D Minor “Souvenir de Florence” Op.70 from 1890, when he feared his creative powers were waning, and Korngold’s astonishingly mature, rich and Romantic Sextet in D Major Op.10 from 1914-16, started when he was only 17 years old.

“The Nash Ensemble brings passion and conviction to both,” says the promotional release, and indeed they do in simply outstanding performances.

Isabella d’Éloize Perron is the violinist on the 2CD set Vivaldi & Piazzolla The Four Seasons, with the Orchestre Filmharmonique under Francis Choinière (GFN Classics gfnproductions.ca).

Isabella d’Éloize Perron is the violinist on the 2CD set Vivaldi & Piazzolla The Four Seasons, with the Orchestre Filmharmonique under Francis Choinière (GFN Classics gfnproductions.ca).

There’s a real freshness to the Vivaldi, with a resonant recording enhancing a spirited, animated and really effective performance. The same approach works wonderfully well in Piazzolla’s Las cuatro estaciones porteñas - The Four Seasons of Buenos Aires, four individual pieces written for his bandoneón quintet and not originally intended as a suite; they are heard here in the terrific 1990s adaptation by Leonid Desyatnikov for violin and string orchestra that incorporates direct quotes from the Vivaldi Seasons.

Perron draws a magnificent sound from her 1768 Guadagnini violin in riveting performances, with Choinière and the orchestra adding significantly to a superb release.

Violinist Francesca Dego admits that the Brahms & Busoni Violin Concertos make an unusual pairing but says that “one of the reasons I fell in love with Busoni’s concerto is that it is permeated with the spirit of the Brahms.” Dalia Stasevska conducts the BBC Symphony Orchestra (Chandos CHSA 5333 chandos.net/products/catalogue/CHAN%205333).

Violinist Francesca Dego admits that the Brahms & Busoni Violin Concertos make an unusual pairing but says that “one of the reasons I fell in love with Busoni’s concerto is that it is permeated with the spirit of the Brahms.” Dalia Stasevska conducts the BBC Symphony Orchestra (Chandos CHSA 5333 chandos.net/products/catalogue/CHAN%205333).

Brahms and Busoni had a somewhat uneven relationship, but Busoni certainly respected the older composer’s music. His Violin Concerto in D Major, Op.35a K243 was premiered a few months after Brahms’ death in 1897, and although initially favoured by players like Kreisler and Szigeti its popularity gradually faded. It’s certainly very “Brahms” in nature, with influences of Liszt in its structure, and clearly will repay repeated listening.

There’s a direct Busoni link to the Brahms Violin Concerto in D Major, Op.77, with Dego using Busoni’s cadenza (with timpani accompaniment) in the first movement of a thoughtful performance that perfectly displays Dego’s luminous, crystal-clear tone.

Violinist Leonidas Kavakos stopped playing Bach in public for quite some time so that he could examine his relationship with the music and recalibrate his baroque technique. His 2022 CD of the Sonatas & Partitas was his first Bach recording, and he has followed it with his new release Bach Violin Concertos with the ApollΩn Ensemble (Sony Classical 19658868932 sonyclassical.com/releases/releases-details/bach-violin-concertos).

Violinist Leonidas Kavakos stopped playing Bach in public for quite some time so that he could examine his relationship with the music and recalibrate his baroque technique. His 2022 CD of the Sonatas & Partitas was his first Bach recording, and he has followed it with his new release Bach Violin Concertos with the ApollΩn Ensemble (Sony Classical 19658868932 sonyclassical.com/releases/releases-details/bach-violin-concertos).

The four concertos are all for solo violin – no Double Concerto here – and include two transcribed from harpsichord concertos – the Concerto in D Minor BWV1052R and the Concerto in G Minor BWV1056R – in addition to the Concerto No.1 in A Minor BWV1041 and the Concerto in E Major BWV1042.

Kavakos decided to go with the smallest possible ensemble of five string players (one per part) and harpsichord, with the result being a light, intimate and well-balanced sound in which the soloist is never placed too far forward but always seems to be an integral part of the ensemble.

Cellist Trey Lee describes Seasons Interrupted as “a musical narrative that confronts our climate crisis, which every year is distorting the behavior of nature’s four seasons beyond recognition.” Georgy Tchaidze is the pianist, and Emilia Hoving conducts the English Chamber Orchestra (Sigma Classics SIGCD791 signumrecords.com/?s=seasons+interrupted).

Cellist Trey Lee describes Seasons Interrupted as “a musical narrative that confronts our climate crisis, which every year is distorting the behavior of nature’s four seasons beyond recognition.” Georgy Tchaidze is the pianist, and Emilia Hoving conducts the English Chamber Orchestra (Sigma Classics SIGCD791 signumrecords.com/?s=seasons+interrupted).

Lee’s arrangements of 4 Schubert Lieder – Im Frühling (Spring); Die Sommernacht (Summer Night); Herbst (Autumn); and Gefrorne Tränen (Frozen Tears, from Die Winterreise) – represent the untainted Past.

A terrific performance of Lee’s highly effective arrangement of Piazzolla’s Las Cuatro Estaciones Porteñas for cello and string orchestra embodies the Present and the rise of 20th-century industry, while the Future is represented by the striking Cello Concerto by Finnish composer Kirmo Lintinern (b.1967), an imaginary journey through a possible climate-changed future with no recognizable seasons.

With 16 Histoires de guitares III the Canadian guitarist David Jacques returns with yet another fascinating selection of guitars from his astonishing private collection (ATMA Classique ACD2 2868 atmaclassique.com/en).

With 16 Histoires de guitares III the Canadian guitarist David Jacques returns with yet another fascinating selection of guitars from his astonishing private collection (ATMA Classique ACD2 2868 atmaclassique.com/en).

Ten of the instruments on this disc were built by the best 19th-century luthiers; there are also three from the late 1700s and three more recent guitars from 1940, 1993 and 2017. Each instrument is illustrated in full colour, along with its history and with information on the composers of the selected works, all chosen to best illustrate the individual qualities of the instruments and which produce a wide range of tonal colours.

Those composers include Coste, Aguardo, Carulli, Giuliani and a host of lesser-known names, all wonderfully presented with faultless technique and admirable sensitivity.

In Time, the new CD from the Aros Guitar Duo of Simon Wildau and Mikkel Egelund is a tribute to the city of Aarhus (Aros being the old Norse name) where the duo started (OUR Recordings 8.226919 ourrecordings.com).

In Time, the new CD from the Aros Guitar Duo of Simon Wildau and Mikkel Egelund is a tribute to the city of Aarhus (Aros being the old Norse name) where the duo started (OUR Recordings 8.226919 ourrecordings.com).

The clock in the city hall bell tower plays In vernalis temporis, a Danish melody from around 1500. When the duo premiered Asger Buur’s I fordret (In the spring) in 2018 they asked that he use the tune in the work, and the idea for a complete concert programme was born, with five newly commissioned works added in the next three years.

All six works here incorporate the theme in some fashion. Buur’s original piece is joined by Martin Lohse’s Ver, Peter Bruun’s Dark is November, Rasmus Zwicki’s In Time, John Frandsen’s Rollercoaster and Wayne Siegel’s bluegrass-inspired Vernalis Breakdown. All are finely crafted and impressive works, given equally impressive performances by the duo.

Guitarist Aaron Larget-Caplan is back with his 11th solo album, and second celebrating Spanish musical heritage with Spanish Gems, a collection of works from the classical and flamenco repertoire (Tiger Turn 888-11 ALCguitar.com).

Guitarist Aaron Larget-Caplan is back with his 11th solo album, and second celebrating Spanish musical heritage with Spanish Gems, a collection of works from the classical and flamenco repertoire (Tiger Turn 888-11 ALCguitar.com).

Included are Tárrega’s Capricho Arabe and Adelita, Esteban de Sanlúcar’s Panaderos, Albeniz’ Asturias, Gaspar Sanz’ Canarios from Suite Española, Emilio Pujol’s El Abejorro and – perhaps somewhat surprisingly – the ubiquitous Spanish Romance, hardly worthy of inclusion in “a collection of masterpieces.”

Torroba’s three-movement Sonatina closes a thoroughly enjoyable – albeit brief at 35 minutes – CD full of Larget-Caplan’s customary clean and sensitive playing.

The Lost Generation

The Lost Generation