To say that these past sixteen months have been exceptional is, at this point, a cliché. Even calling it a cliché has become a cliché! And yet, it’s hard not to feel as though this summer represents a major turning point – and, hopefully, a bookend – in the experience of the pandemic, at least in Toronto.

To say that these past sixteen months have been exceptional is, at this point, a cliché. Even calling it a cliché has become a cliché! And yet, it’s hard not to feel as though this summer represents a major turning point – and, hopefully, a bookend – in the experience of the pandemic, at least in Toronto.

Case rates are down, vaccine rates are up, and businesses are reopening, albeit at reduced capacity. Live music is still not back, though it is slowly reappearing; as of the writing of this article, there is a pilot project in development that allows musicians to play on the ad hoc CaféTO patios in three wards (Davenport, Beaches-East York, and Toronto-Danforth).

It is only a matter of time, however, before we see the return of live music, both outdoors and in; by September, I expect to be back to the normal format of my column, looking ahead to club offerings for each coming month. Thus, in the spirit of celebrating the beginning of the end of lockdown life, it seems like a propitious time to revisit and reflect upon some of the issues, movements, and community responses that have informed the Southern Ontario jazz (and jazz-adjacent) scene throughout the pandemic.

Venue Closures and Re-openings

It has been immediately reassuring, as lockdown restrictions are gradually lifted, to see (and hear) Toronto’s long-shuttered venues welcoming patrons back for dining and drinks, albeit only outdoors. While it may still be some time until we get to hear music indoors in Ontario, a number of clubs have patios open. Some have even cautiously started programming live music outdoors. At Kensington Market’s Poetry Jazz Café, a spacious, stylish back patio is host to the likes of trumpeter Rudy Ray, vocalist/bassist Quincy Bullen, and other notable young Toronto musicians. (Programming at Poetry tends to focus on groove-oriented jazz, with both vocalists and instrumentalists in the bandleader chair.) At The Rex, Toronto’s perennial favourite for straight-ahead modern jazz, an expanded outdoor patio is in place for the culinary side of their business, but at The Rex the music happens indoors and spills out to the patio. Rex regulars can but hope.

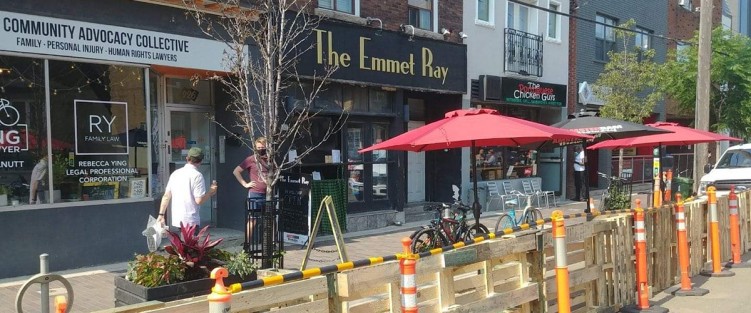

Even as some venues return, others have been lost. The pandemic has hit the service industry hard, and – especially for venues without food programs that could be easily adapted to a takeaway format – closures were all but inevitable. 120 Diner, N’Awlins and Alleycatz have all been shuttered; others, including The Emmet Ray, have maintained themselves by converting their existing space to a bottle shop and focusing on delivery-friendly food options.

Virtual Concerts and Social Media

Early in the course of the pandemic, virtual concerts were the name of the game, from living-room livestreams undertaken by individual musicians to professionally produced, pre-recorded performances offered by major festivals. This year, as we near the end of what will very likely be our last major lockdown, the number of purely virtual concerts seems to be tapering, which in my view is a hopeful sign. In the United States, where mass vaccination efforts took place earlier and with greater speed than here in Canada, live concerts have already been taking place for some time; scroll through your favourite American jazz musician’s social media and you’ll be likely to see posts about outdoor festival concerts, indoor club appearances and, increasingly, advertisements for tours happening later this year and early in 2022.

Even in Canada, where, at the time of this article’s composition, close to seven million of us have been fully vaccinated, it is becoming more common to see maskless musicians in studios, concert halls and other indoor recording scenarios.

Reactions to virtual concerts have been mixed. This time last year, I interviewed Kodi Hutchinson, artistic producer of JazzYYC and organizer of the Canadian Online Jazz Festival, and Molly Johnson, artistic director of the Kensington Market Jazz Festival. Both were in the midst of preparations for their respective festivals, which were broadcast entirely online last year. During our interview, Hutchinson told me that the COJF was, in part, a fact-finding mission, with the goal of gathering data about audiences’ online music-viewing habits. The larger aim, he said, was to help concert presenters be better online, and to be prepared for a future in which livestreaming options at major jazz festivals were more of a norm.

From the performer perspective, few musicians seem to genuinely love livestreaming, compared to the real thing; in a piece that I wrote for this magazine’s December issue, the consensus seemed to be that livestreaming, absent an audience, is a poor substitute for the real thing. The prospect of remote audiences being able to livestream shows with an audience, however, remains interesting, and it remains to be seen how (and if) concert presenters will incorporate livestreams into their future events.

Equity and Reckoning in Academia

In September of last year, I wrote about the enduring whiteness of Canadian post-secondary jazz education, the calls for changes in leadership, staffing and curricula at a number of Canadian jazz programs, and about the committee to address anti-racism, equity, diversity and inclusion issues (AREDI) at U of T.

Now on the cusp of a new academic year, both the U of T jazz program and its parent institution, the Faculty of Music, are in the midst of ongoing major issues. More than 800 students, faculty and alumni have signed an open letter to the school, asking administration to address “historical and ongoing misogyny and systemic inequalities.” Amongst the stories being shared, common complaints include the suppression and silencing of survivors’ voices, a reticence to act on reports of gender-based harassment and sexual assault, and a culture of denial when dealing with charges against faculty members and students.

Within the jazz program, similar issues are at play. Tara Kannangara and Jacqueline Teh, both sessional faculty members and members of the coalition #thisisartschool, have been part of efforts to address systemic issues within the department. On June 11, both released a joint open letter detailing their experience working within the department and the Faculty of Music. In the letter, Kannangara and Teh describe feelings of “psychological abuse and discrimination” in their dealings with U of T Jazz and the Faculty of Music, including being subject to “a level of problematic behaviour and intense scrutiny” in a masterclass they presented.

I have viewed both letters, and the overall impression they convey is of an institution that is more concerned with maintaining the status quo than with making deeper systemic change. As the prospect of a “normal” September looms, the choices made at U of T are liable to have far-reaching consequences in the coming years, for better or for worse.

Colin Story is a jazz guitarist, writer and teacher based in Toronto. He can be reached at www.colinstory.com on Instagram

and on Twitter.