Jessye Norman (singing), New York City.

Jessye Norman (singing), New York City.

Hunt down the photograph of Jessye Norman that graces our cover in the Prints & Photographs Online Catalog of the US Library of Congress in Washington D.C. and you will discover that it was taken in 1988 by acclaimed photographer Annie Leibovitz and titled “Jessye Norman (singing), New York City.” (The cutline for the image in the version we received from Universal Music to make our cover from is titled “Jessye Norman is Carmen,” but we’ll get back to that factoid once we’ve browsed the Library’s holdings a little further.)

The photo on our cover seems to be the only Leibovitz photo in the library’s print and photo online catalogue. But it’s far from the only Jessye Norman image listed there: there are photos of her singing during Bill Clinton’s 1997 inauguration and, the previous year, at the 1996 Democratic National Convention; there are sketches of her, alone and with conductor Seiji Ozawa, by illustrator Tracy Sugarman; and there is a photograph listed of her singing, in the Capitol Rotunda in June 1999, during a ceremony to award the Congressional Medal of Honour to Rosa Parks, the Alabama seamstress whose 1955 refusal to give up her seat on a Montgomery bus to a white man could be said to have sparked the campaign of disobedience that launched the American civil rights movement. ‘’This will be encouragement for all of us to continue until all people have equal rights,’’ the then-86-year-old Parks said in accepting the medal, just moments after Norman’s voice filled the Rotunda with the strains of John Rosamond Johnson and James Weldon Johnson’s anthemic Lift Every Voice and Sing.

Sing a song full of the hope that the present has brought us;

facing the rising sun of our new day begun,

let us march on till victory is won.

“Jessye Norman is Carmen”

If one searches a list of all the Library’s holdings beyond prints and photographs, a sense of the full scope and scale of Norman’s artistic contribution over the decades starts to emerge: films, interviews, her own 2014 memoir, Stand Up Straight and Sing!, and almost 100 audio recordings, from spirituals to song cycles, from sacred works to the grandest of grand opera, reflective of an astounding technical range (she has sung soprano, mezzo-soprano and alto roles throughout her career), broad and adventurous musical tastes, and a lifetime of collaboration with artistic colleagues who, like her, are among the greatest of the great.

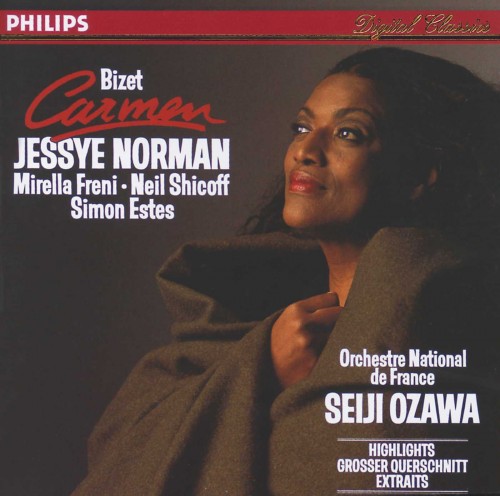

Tucked away among these recordings is one from 1988, the year in which our cover photo was taken, which sheds light on the “Jessie Norman Is Carmen” cutline under the file of the photograph sent to us by Universal Music for our cover use. It is a Philips recording of Bizet’s Carmen, with Norman in the title role, and Mirella Freni, Neil Shicoff, and Simon Estes, among others, in the cast. It was made between July 13 and 22 1988, in the Grand Auditorium de Radio France, with Seiji Ozawa conducting the Orchestre national de France. Sure enough, if you hunt out images of the cover of that record, you will find yourself face to face with this same photograph, only in colour. You would never think, though, looking at the photograph in that context, that it was ever intended for any other purpose. It seems to be a picture of Norman inhabiting a role as fully and easily as the blanket drawn around her.

Tucked away among these recordings is one from 1988, the year in which our cover photo was taken, which sheds light on the “Jessie Norman Is Carmen” cutline under the file of the photograph sent to us by Universal Music for our cover use. It is a Philips recording of Bizet’s Carmen, with Norman in the title role, and Mirella Freni, Neil Shicoff, and Simon Estes, among others, in the cast. It was made between July 13 and 22 1988, in the Grand Auditorium de Radio France, with Seiji Ozawa conducting the Orchestre national de France. Sure enough, if you hunt out images of the cover of that record, you will find yourself face to face with this same photograph, only in colour. You would never think, though, looking at the photograph in that context, that it was ever intended for any other purpose. It seems to be a picture of Norman inhabiting a role as fully and easily as the blanket drawn around her.

It’s worth noting too, though, that by 1988, fully two decades after a major vocal competition win in Munich in 1969 launched her on an A-list European career, Norman was only five years into a Metropolitan Opera mainstage career, albeit one that would continue until 1996. But Carmen was not a role she ever played at the Met.

JESSYE NORMAN, GGF Laureate, Toronto 2019

On Wednesday February 20, 2019, at the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts in Toronto, somewhere during the course of a gala concert titled The Glenn Gould Prize Celebrates Jessye Norman, she will accept, in person as all the Prize’s laureates do, the Glenn Gould Foundation’s Glenn Gould Prize awarded her in April 2018. In a line of 12 Laureates stretching back to R. Murray Schafer in 1987, Norman is the first woman to receive the award.

Glenn Gould Prize laureates seldom perform at their own concerts, but generally have a significant say in who will perform; even by GGF standards this year’s promises to be quite a lineup: the Canadian Opera Company Orchestra; soprano Nina Stemme and lyric soprano Pumeza Matshikiza; tenor Rodrick Dixon and bass-baritone Ryan Speedo Green; soprano Sondra Radvanovsky and mezzo-sopranos Wallis Giunta and Susan Platts; American jazz singer Cécile McLorin Salvant, and the Nathaniel Dett Chorale directed by Brainerd Blyden-Taylor. Conductors Bernard Labadie, Donald Runnicles, Jean-Philippe Tremblay and Johannes Debus will also participate. And Viggo Mortensen, chair of last April’s Glenn Gould Prize Jury that awarded the prize to Norman will also be there.

It’s a stellar array (with of course the attendant danger of turning into an all-aria-no-recitative operatic highlight reel – all climaxes with no foreplay or interplay). But what the heck, there’s a place for those things too. And there are two participants in particular, about whom I’m particularly curious.

One is jazz singer/songwriter, Cécile McLorin Salvant, whom Norman, as each GGF laureate gets to do, has chosen to receive the Protégé Prize that goes with the award. It’s always an interesting insight into the mind of the laureate to see whom they choose as protégé: in 1996, pioneering Japanese composer Toru Takemitsu selected fellow composer Tan Dun; in 1999, Yo-Yo Ma chose pipa player Wu Man who became one of his closest Silk Road collaborators; in 2008, Sistema founder José Maria Abreu named Gustavo Dudamel, Sistema’s best-known alumnus; and in 2011 Leonard Cohen, not untypically, broke the pattern by naming the Children of Sistema Toronto, rather than an individual, as his protégés. In naming McLorin Salvant, Norman said this: “Singer, songwriter…a unique voice supported by an intelligence and full-fledged musicality which light up every note she sings. There is an intense, yet quiet confidence in her music-making that I find compelling and thoroughly enjoyable.”

One is jazz singer/songwriter, Cécile McLorin Salvant, whom Norman, as each GGF laureate gets to do, has chosen to receive the Protégé Prize that goes with the award. It’s always an interesting insight into the mind of the laureate to see whom they choose as protégé: in 1996, pioneering Japanese composer Toru Takemitsu selected fellow composer Tan Dun; in 1999, Yo-Yo Ma chose pipa player Wu Man who became one of his closest Silk Road collaborators; in 2008, Sistema founder José Maria Abreu named Gustavo Dudamel, Sistema’s best-known alumnus; and in 2011 Leonard Cohen, not untypically, broke the pattern by naming the Children of Sistema Toronto, rather than an individual, as his protégés. In naming McLorin Salvant, Norman said this: “Singer, songwriter…a unique voice supported by an intelligence and full-fledged musicality which light up every note she sings. There is an intense, yet quiet confidence in her music-making that I find compelling and thoroughly enjoyable.”

The other participant I’m particularly looking forward to hearing in the context of the gala is the Nathaniel Dett Chorale, under conductor Brainerd Blyden-Taylor, for the simple reason that, when people’s chosen creative pathways intersect, there’s always a chance that, at one of these intersections, the individuals in question will actually cross paths to interesting effect.

For Blyden-Taylor and the Chorale, the Norman Celebration concert comes at an interesting juncture. The week before, on February 13, the day after Norman arrives in town, they will be celebrating their own 20th anniversary as a choir; the following month, March 23, they will head to Hampton, Virginia for the 70th anniversary of Nathaniel Dett’s founding of the school of music there.

For Blyden-Taylor and the Chorale, the Norman Celebration concert comes at an interesting juncture. The week before, on February 13, the day after Norman arrives in town, they will be celebrating their own 20th anniversary as a choir; the following month, March 23, they will head to Hampton, Virginia for the 70th anniversary of Nathaniel Dett’s founding of the school of music there.

Norman has long been part of Blyden-Taylor’s inspirational musical frame of reference. “My consciousness of her goes back to my youth in Barbados in the mid-60s” he says, “and even more so after I came to Toronto in 1973 to be musical director at my uncle’s church. She was an ongoing part of my listening in terms of a sound ideal in terms of performance of spirituals, in my work with the Orpheus Choir, and workshops I was asked to do across the country, helping other choirs with interpretation of spirituals. You’d have to say she was one of those voices that were pivotal in terms of reading of the spirituals.”

Norman was top of the list of people Blyden-Taylor approached to be honorary patron of the Chorale when they started in 1998. “But she very respectfully declined at the time, and as you know, Oscar Peterson, also a Glenn Gould Prize laureate, in fact, accepted, and remained so until his death. Maybe it’s time to ask her again!”

With the number of events Norman will be attending in the week leading up to the celebration concert on February 20, Blyden-Taylor is unsure whether the Dett Chorale’s concert at Koerner Hall will make it onto Norman’s dance card. “It would be nice. But the fact that this is all happening during Black History month means there’s no shortage of partners already predisposed to program events this month. So she will be busy!”

Regarding the fact that, for whatever reasons, this celebration has been timed to take place during Black History Month, Blyden-Taylor is philosophical. “I think back to a time in my life when I was rather upset that I seemed only to be asked to do workshops on Afrocentric music and spirituals. But one of the people to whom I was lamenting, invited me to look at it as a glass half full, as a doorway to communication. We constantly have to be pushing the boundaries, in fact we are constantly pushing the boundaries, even when nobody is watching, so it’s better to simply accept that Black History Month gives an entrée to audiences we might otherwise not reach at all. After all, to take another example, the United Nations declared 2015 to 2024 to be the decade of people of African descent, and the decade started then, even if it took till January 2018 for our own Prime Minister to publicly acknowledge the fact.”

As to the Dett Chorale’s role in the gala concert, they are slated to perform three pieces. “Two by Moses Hogan, I’d say – our Youtube video of his Battle of Jericho has logged thousands of hits. And his Didn’t my Lord Deliver Daniel?” The third piece will, fittingly, be by Nathaniel Dett himself. “His Go Not Far From Me, O God is a wonderful example of Dett’s writing, juxtaposing two melodic ideas from the canon of spirituals and with a wonderfully high baritone/low tenor solo part to it; I have suggested that one of the visiting operatic soloists might want to do it with us. I don’t know whether it will happen or not, but we’ll be ready. I know Jessye asked for there to be spirituals on the program. It’s music very near and dear to her heart.”

The Glenn Gould Foundation in 1988

Cycling back to the year our cover photograph was taken, it’s worth noting that in 1988, with Jessye Norman already in her artistic prime, the Glenn Gould Foundation was in its infancy, having awarded its first prize just the previous year to composer and visionary R. Murray Schafer. In the words of jury member, Sir Yehudi Menuhin – who went on to be the laureate of the Second Glenn Gould Prize – Schafer was being honoured for his “strong, benevolent, and highly original imagination and intellect, a dynamic power whose manifold personal expression and aspirations are in total accord with the urgent needs and dreams of humanity today.”

It’s important to note the Janus-like nature of Menuhin’s citation for Schafer’s award: the words could as easily be about the individual in whose name, and spirit, the Prize is awarded, as about the laureate of the day. As such, this first citation was an aspirational benchmark that has remained fundamental to the GGF’s sense of mission to this day: Gould himself, as a timelessly creative original, sets a standard of engaged creativity for the GGF’s jurors that demands of them that they choose worthy recipients. It’s win-win. The Prize adds lustre to the achievements of its laureates; over time the consistent, cumulative calibre of its laureates adds lustre to the Prize.

Another throughline in the GGF’s 30-year history of presenting the award is the care taken in planning not just a celebration concert, but all the events leading up to, or surrounding it. For it is often in these other events that a more fully rounded portrait of the laureate can emerge.

Starting things off, a three-day festival of film, February 11 to 13 in partnership with TIFF, titled “Divine: A Jessye Norman Tribute” features screenings (including a 1989 film, Jessye Norman Sings Carmen, by Albert Maysles on the making of of the Seiji Ozawa-conducted recording mentioned earlier in this story), and a conversation between Norman and the Canadian Opera Company’s Alexander Neef.

There will also be a rare, public, three-hour Jessye Norman masterclass for voice and opera students, in Walter Hall at the U of T Faculty of Music, on Friday February 15. Free to the public, it should afford the opportunity to witness Norman directly engaged in arts education, a cause for which she is an untiring and passionate advocate.

And an all-day symposium titled “Black Opera - Uncovering Music History” at the Toronto Reference Library, on Saturday, February 16 from 11am to 5pm, in partnership with the Toronto Public Library, will “trace the heroic struggles of pioneering artists of African origin to enter the operatic world, their fight for acceptance and recognition, their triumphs and accomplishments.” It will include, in its final hour, a conversation with Norman herself. Interestingly, the indefatigable Norman’s own latest multimedia project, launched in 2018, titled “Call Her By Her Name!” revolves around “the name and legacy of the first African-American opera singer to perform, in 1893, on the main stage of Carnegie Hall – Madame Sissieretta Jones.” So this should be a fascinating conversation.

Of all the events programmed, so far, for the visit, there’s one that for me captures the essence of why the match between the GGF and Norman is a lustrous one; and, fittingly, it will happen out of the public eye. Titled “Freedom Through the Arts Workshops” it will bring together students from the Jessye Norman School of the Arts and the students of Sistema Toronto (laureate Leonard Cohen’s 2011 protégés).

Of all the events programmed, so far, for the visit, there’s one that for me captures the essence of why the match between the GGF and Norman is a lustrous one; and, fittingly, it will happen out of the public eye. Titled “Freedom Through the Arts Workshops” it will bring together students from the Jessye Norman School of the Arts and the students of Sistema Toronto (laureate Leonard Cohen’s 2011 protégés).

Norman helped establish the Jessye Norman School of the Arts in her hometown of Augusta, Georgia, in 2003, to provide arts education to students from economically disadvantaged neighbourhoods. In 2011, following the presentation of the Eighth Glenn Gould Prize to Dr. José Antonio Abreu, Sistema Toronto was founded to bring the power of music education into the lives of children from this city’s priority neighbourhoods. In this potentially transformative exchange, 15 students from a Jessye Norman inspired initiative in Augusta will travel to Toronto for four days of workshops and collaboration with students engaged in a thriving Toronto initiative directly inspired by the existence of the Glenn Gould Prize.

Drawing each new role afforded her around her shoulders like a blanket, out of the spotlight, away from the footlights, Norman’s work continues, even when no-one is watching.

David Perlman can be reached at publisher@thewholenote.com