Most of our memorable live musical moments are things we plan for, but they are not necessarily the most memorable. Because there are other kinds of musical moments that tend to stand out even more – the ones where we stumble across some music unexpectedly and find ourselves enchanted – sharing the moment with complete strangers similarly bewitched. (Provided that, in such situations, we are prepared to take a chance on sticking around, because you never know, these days, when an accidental encounter with strangers might become too personal.)

And it’s getting even harder to do that – risking socializing in public space – when we could continue cocooning in all the ways the pandemic taught us to like: food dashed to our doors on demand; earbuds delivering private playlists to our blinkered brains when we’re out in public; and “personal digital assistants” of ever-increasing sophistication enabling conversation with someone half a world away more comfortably than turning to smile wow! to the stranger beside us, sharing a moment of unanticipated musical enchantment.

The thing that makes unanticipated musical moments such as these most memorable is that they give us permission: to stare or laugh or dance or sing along; or find ourselves listening with fresh ears to something we thought we knew; or to something it would never have occurred to us we might like. And that we might actually plan to seek out another time.

“Enchanted moments as resistance”

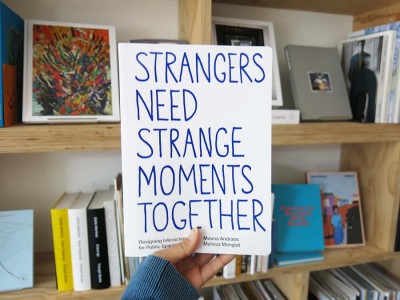

The phrase above is from a book I was lucky enough to stumble across this past holiday season, courtesy of someone who lives in Montreal but came to Toronto for a bit of family time. The book is called Strangers Need Strange Moments Together: Designing Interaction for Public Spaces. It was co-written by Mouna Andraos and Melissa Mongiat, owners of a woman-led Montreal-based company called Daily tous le jours engaged in “seeking new models for living together.”

As they describe it: “We have been creating interactive art in public spaces around the world for fifteen years. Using music, dance, art, and other mediums to emphasize the joyful, magical, and unexpected, we create moments of connection and care between strangers.”

Make no mistake though: “enchantment” the way Andraos and Mongiat use the word isn’t fluffy. It’s serious business. “How we socialise is at the root of how values are nurtured and shared – holding together what we call society today. We need informal social connections to survive. Public places that notably supported ad hoc connections are now filled with zombies on phones.”

How to “coax the public out of their bubbles” is, for them, the critical question: “Beyond memes. In the flesh … After all, we are living in times of acute global polarization … yet we connect mostly to people we agree with, and mostly in images and videos – and mostly online – through communication channels aimed at manipulating our thoughts, endlessly dividing us, for the profit of only a few.”

“It may feel strange to smile, dance or make music with a stranger these days. But connecting with others through joy, bringing bodies together in laughter, is a proposition we need for the survival of what’s left of our humanity. Enchanted moments as resistance. Whether you call it art or infrastructure, strangers need strange moments together.”

Music as a congregational art

Set aside for a moment the idea that “congregating” only means getting together for overtly religious reasons (although it certainly can). If instead we take it to mean voluntarily gathering together with a mutually agreed purpose in mind, then the idea of music as a congregational art fits the description of how Andraos and Mongiat think of music – as a “ powerful tool in the interaction designer’s kit … as a feedback mechanism for participation.”

Not when people are “stuck in their heads or on their phones, and not terribly aware or connected to their surrounding or each other …but when music become a collective experience – whether you are there as a spectator or part of the performance – a kind of magic happens: we become present, grounded for a moment in time and place along with a group of strangers.”

For all these reasons, talking about Andraos and Mongiat’s book in this spot felt like a hopeful place to start 2026. The digital communication channels they describe as “aimed at manipulating our thoughts, endlessly dividing us” are now, thanks to AI, entering an even more menacing state of being. We are rapidly approaching a time where the only way of verifying the “fake” from the “real” (whether it be musical, visual, or political) will be when we congregate in real time and space.

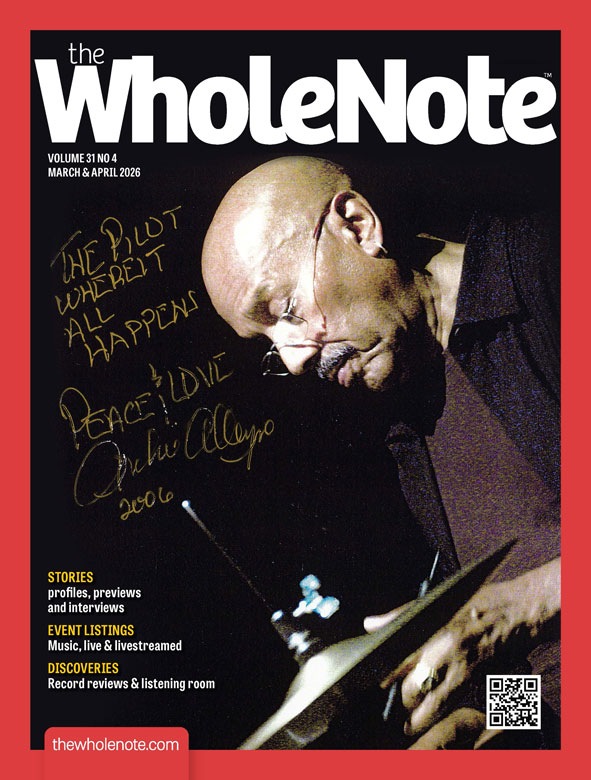

And that is where danger translates into opportunity. The core work The WholeNote has done for the past 30 years documenting public opportunities to congregate for live music takes on an even greater significance: an analogue confirmation of our collective humanity in the face of digital bewilderment.

So for you, our faithful readers, we wish you many “enchanted moments” of live music in 2026. And welcome to the resistance.

David Perlman can be reached at publisher@thewholenote.com.