“And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?” W.B Yeats

With apologies to W.B. Yeats, “slouching towards Bethlehem” is a perfect description of me as I walk the 15 minutes down Bathurst Street from home to the Toronto Island Airport. I am Newark bound, with my one overstuffed carry-on bag on my shoulder. It’s 6:30am on a Friday, and I have to be on the bus to Bethlehem at 10am. So I have not had time for shower, shave or coffee this balmy May 8 morning.

But I make my Porter flight to Newark with time to spare and find my bus; my little spring adventure is underway.

Modern-day Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, sits like two halves of a cracked soup bowl, with the Lehigh River zigzagging through the crack between, flowing eastward towards Easton, one of Bethlehem’s two sister cities. Easton is at least as famous for being the headquarters of Crayola as Bethlehem is for being home to the longest running annual Bach festival in North America. (But Bach, I am happy to say, yields 151 million google results compared to Crayola’s 15.5 million.)

Modern-day Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, sits like two halves of a cracked soup bowl, with the Lehigh River zigzagging through the crack between, flowing eastward towards Easton, one of Bethlehem’s two sister cities. Easton is at least as famous for being the headquarters of Crayola as Bethlehem is for being home to the longest running annual Bach festival in North America. (But Bach, I am happy to say, yields 151 million google results compared to Crayola’s 15.5 million.)

The Hotel Bethlehem (where I get my shower, but shortly after noon) is in the northern half of the town, and boasts among its famous guests, according to the cards in the elevators, the Dalai Lama and Jack Nicklaus. It was built in the 1920s with steel girders from the Bethlehem steel mill, now a rusting hulk looming like a spectacular post-modern art installation alongside the river between the two halves of the town. Looking straight down from my ninth floor window I can see the original mid-18th-century buildings that speak to the town’s pre-1776 Moravian settler origins, a heritage that stretches for block after remarkable block in the old town.

And looking straight out from that same window I can see all the way over the Lehigh River to the steeper slope of South Bethlehem. Halfway up that slope is the Packer Church on the campus of Lehigh University. Church and campus between them will host most of the performances in this, the second weekend of the 109th iteration of the Bethlehem Bach Festival. The first week’s program will be repeated in its entirety for a new group of pilgrims. And as they did the previous weekend, for the next two days little white shuttle buses will circle endlessly between the town’s key hotels on the north side of the river and the festival venues to the south.

Two days later I am Newark bound again, with a head full of the history of a town I previously had no awareness of, and with a heart full of the music of Bach, presented in a context that felt less like a festival than a glorious friendship between a great composer and the orchetra, conductor and choir at the heart of an extraordinary town.

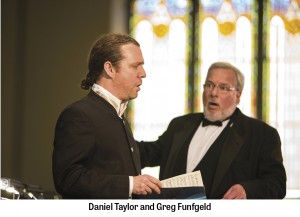

For decades Canadian performers have been making this pilgrimage, even if Canadian audiences have not. Take countertenor Daniel Taylor, for example, one of this year’s stellar Canucks. He’s been coming here for well over a decade, he tells me.

“I heard first about the festival when Catherine Robbin was getting ready to retire,” he says. She had been singing at the festival on a regular basis and encouraged Greg Funfgeld, the festival’s music director to go and hear Taylor. “He came to hear me at the Met in 1999,” Taylor says. “I was in a show with Brian Asawa, David Daniels, Stephanie Blythe and Jennifer Larmore.”

“Sounds like Handel’s Caesar,” I say. “Were you the bad guy?”

“No it was a small role, actually,” he says. “What was interesting was he was specifically looking for a middle voice. So there was Larmore and Blythe and these two other countertenors who were really at the top of their game right then, and he called me right after and asked if I would come and sing some Bach for him.” Taylor met with Funfgeld in New York and “the next thing you knew I was on the way to Bethlehem.”

That was in 1999, and Taylor has been at every festival since. “There were times when I have had bookings in Germany where I could only do one of the two weekends. Greg prefers to have singers who will do both weekends, but he was very flexible. He is totally loyal to the singers that he likes.”

“Most wonderful, he is totally approachable, with no airs about him, and yet his understanding of the music is quite profound. His demands are quite specific; he knows about the text; and his ears are very, very keen. So any wrong turn from anywhere in the orchestra he’s right on it, and in a way that I’d say is less obvious than say someone like Bernard Labadie – Labadie who’s a great technician. Greg might seem more casual about it but in fact he has these standards he wants to achieve and he holds onto singers that he feels understand him and are open to reaching the same goals.”

Another favourite of Funfgeld’s, Taylor tells me, is tenor Charles Daniels. Taylor had sung a St. John’s Passion with Daniels at Tafelmusik and made the suggestion to Funfgeld that he invite Daniels to the Bethlehem Bach Chorus for their recording of the work.

“For that kind of repertoire Charles is probably my favourite singer,” Taylor says, of working with Daniels during the Tafelmusik St. John. “He got up night after night just like it was pouring a cup of tea every night. He did it with such ease, such conviction. I mean, we all did what we could but the show was about Charles. He’s a remarkable, he’s, well, a hero.”

“He’s a wonderful storyteller,” I offer. “It’s a rare talent to be able to get inside the musical story like that.”

“Exactly,” Taylor says. “That’s exactly right. At University of Toronto that’s what we work on so much at the Faculty of Music. I mean, students and other performers were given the gifts they have to work with and we work as hard as we can to maintain that. But its quite another challenge to teach someone how to tell a story. I’ve been involved in masterclasses, anywhere in the world where I’ve heard a really great, great voice and I’ve felt ‘what’s missing here?’ and it’s usually that. It’s a skill which can also to some extent be taught, but really you know it’s a question of having to be open to communicating with people and less self-critical.”

So often, he says, students and some professionals are concerned above all with developing what they think will be an unfailing technique. “I joke with students when they arrive in the studio, especially if they’re there to do their master’s; they think you’re going to give them a key to open the secret area of resonation or secret breathing technique or whatever that’s going to give them – and all you can really tell them is ‘it’s a long journey, its a very long journey.’”

Talking to Taylor now, compared to even a few years ago, it’s interesting to see how deeply the commitment to teaching has taken hold, along with his still astoundingly busy performing and recording pursuits. And the teaching aspect feeds off the other as he ropes his duet partners and other performance collaborators into his teaching work.

“I mean just last week I had Emma Kirkby in at the faculty – I bring her in every year; I bring in Nancy Argenta as well; I just had Christopher Purves.”

(Purves is the English baritone, who sang the hair-raisingly chilling lead role, opposite Barabara Hannigan, in the Toronto Symphony Orchestra’s recent opera-in-concert production of George Benjamin’s Written on Skin during this spring’s New Creations Festival.)

“So you saw that show?” I ask. “I did,” he says. “I did and I loved it. And I didn’t expect to love it. My experience with new music has been mixed, and I’ve done some of those premieres ... I thought it was an amazing evening, across the board. And I have one fellow [in the show] who worked with me, Isaiah Bell, the tenor, and I was just so pleased; he’s making a name for himself. He was at Tanglewood, he’s recorded with Nagano ... it’s all beginning to happen for him.”

“So, back to Kirkby,” I prompt. “We were talking about musical storytelling and you said last week you brought her in ...”

“The thing about Emma,” he says, “Everything about what Emma does (and I’ve sung with Emma for about ten years, we tour together every year, we do recitals together and I’ve been very lucky, I mean in the last 15 years she refers to me as being her duet partner which is an honour from someone who has been so important not only to early music but to music today) ... the thing about Emma is that when she sings, it’s all about honesty, really, and text. She comes in and she’s not interested really in what noise is happening, it’s all about truth.”

“Ultimately though,” I suggest “Technique still comes into play when you have to trust your instrument to deliver the truth you’ve discovered.” “Yes,” he replies. “And if you haven’t done the hard work at that point then you’re in trouble.”

Taylor’s co-Canadian at Bethlehem this year is Agnes Zsigovics. I hear them together first on the Friday afternoon in duets from Cantata BWV 78 – Jesu, der du meine Seele and then Cantata BWV 23 – Du wahrer Gott und Davids Sohn. Their rapport is striking and their voices together are pellucid, meshing with a harmonic precision reminiscent, I suggest to him, of what one hears in his duet work with his great collaborators – Suzie LeBlanc, Kirkby and Nancy Argenta. “I have to say,” he replies, “For the work I do, the duet projects when I go around, I’ve got a few voices, yes, ... you develop a preference for colours.”

“And Agnes has that?”

“She’s a very special singer” he says. “She is doing her doctorate now at U of T, but actually I met her at U. Of T. Years ago, when I was a visiting artist. We were doing some Bach with Helmut Rilling.”

“I was thinking about those encounters with Rilling earlier,” I remark, “When we were talking about the storytelling aspect. I remember one Rilling masterclass you were in, with a student, a soprano, doing a duet – maybe it was even one of these two duets.”

“Yes,” he replies. “That’s Rilling’s teaching model [pairing guest artist and student]. It’s a wonderful model.”

(In the encounter in question, Rilling had stopped the student to ask her if she knew who her character was speaking to. After the penny dropped that the two singers were not singing to an audience but to each other, the entire performance had transformed in a flash to something unforgettably compelling.)

“I was lucky,” Taylor says. “Rilling never worked with countertenors before. He’s now hired me for many years, mostly for Handel. But I love that recently in an interview someone said ‘but you don’t like countertenors, right?’ and he said I used not to like countertenors.”

Our conversation drifts on and on, for 45 minutes or so: “I feel I am now in the middle of my career as a countertenor, and I’m aware of it, and so I don’t have the advantage of being new ...”. “I haven’t sung at the Canadian Opera Company now since Richard Bradshaw passed away.”

“You did Caesar for them I remember, with Ewa Podles?”

“Yes, that was amazing, and in that one I did play ‘the bad guy.’ Richard had asked if I would do Sesto and I said ‘well you know Richard, Tolomeo is really fun, and I had sung it at Rome ...”

And much more: about male and female alto voices; about Bach on modern and period instruments; about James Bowman and Michael Chance and recording for Sony. And fittingly much more about Funfgeld and the Bethlehem Bach Festival.

All I can do is to promise you “more on the web,” and to promise myself a return visit next spring, slouching down Bathurst Street to Bethlehem, once again to be uplifted and amazed.