Opera-goers heading out of the current COC production of Wozzeck wondering what makes the show’s director/designer William Kentridge tick should make their way to the online Kentridge Studio – a website that is yet another layer to his art. If you do, check out the 1988 essay by Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev in the Reading Room titled William Kentridge’s Ubu Projects.

Opera-goers heading out of the current COC production of Wozzeck wondering what makes the show’s director/designer William Kentridge tick should make their way to the online Kentridge Studio – a website that is yet another layer to his art. If you do, check out the 1988 essay by Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev in the Reading Room titled William Kentridge’s Ubu Projects.

Ubu Roi: Retitled Ubu Rex, Jarry’s play arrived in 1975 South Africa as the first show in the new Nunnery Theatre at the University of the Witwatersrand. Kentridge was in the cast, one of a cluster of individuals who would go on to form the original core of the Junction Avenue Theatre Company, with Malcolm Purkey as its artistic director. “He was in his first year at Wits,” Purkey recalls, “with a wispy mustache and trademark bowler hat.”

The Purkey/Kentridge/Junction Avenue connection would last a decade and a half, during which the company collectively wrote and staged play after play that, one way or another, used farce and absurdity to unmask the state’s tyranny. Their titles tell a story: from The Fantastical History of a Useless Man (1976) to Sophiatown (1986) and Tooth and Nail (1988). By then, Junction Avenue was running out of steam, but one of the things Kentridge took away from it was a newly minted relationship with Handspring Puppet Company founders Adrian Kohler and Basil Jones. Through the 1990s, Kentridge’s defining collaborations with Handspring would range from Woyzeck on the Highveld (1991) to Ubu and the Truth Commission (1997).

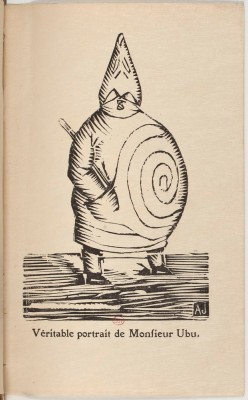

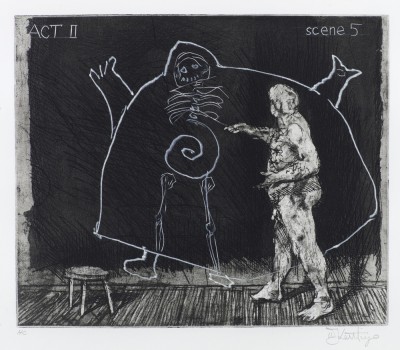

Ubu’s re-entry into Kentridge’s art came two decades after Ubu Rex at the Nunnery. It was sparked in 1996 when he participated in a group show celebrating the centenary of the first Ubu performance. He contributed a series of eight prints in which he layered chalk representations of Jarry’s original Ubu cartoon with his own drawings of a naked man, based on photos of himself in the studio. The resulting blackboard-style prints, titled Ubu Tells the Truth, later evolved into the complex animations for Ubu and the Truth Commission.

Kentridge has often talked about how switching to drawing in charcoal changed his approach to art because it enabled a process of layering. With Handspring, layering is extended into powerful new digital realms.

From Woyzeck to Wozzeck: The 1991 Handspring/Kentridge Woyzeck on the Highveld, as did Alban Berg’s Wozzeck, drew on Georg Büchner’s 1837 stage play Woyzeck. Kentridge’s director’s notes for Woyzeck on the Highveld are also in the Studio Reading Room.

In the notes for the original production, he writes about seeing the Büchner play in the 1970s and how characters and images from the play have floated on the edges of his consciousness since then, and that it seems to him “that the anguish and desperation of Büchner’s text does not need to be locked into the context of Germany in the 19th century.”

In the notes for a European revival of the play (2009-2013) he comments wryly on “the strange, convoluted world of oppression and enlightenment that constituted Prussia in the 19th century, [where] there was a law which stated that anyone condemned to death, had first to be examined by a psychiatrist before he could be executed.”

It was one such psychiatric report – about a private in the army who murdered his wife – that formed the basis of Büchner’s play, which remained an unfinished series of fragments at the time of the author’s death at the age of 23.

Since then, its mixture of fragmentation, rationality and irrationality has made it a central text in 20th-century theatre – a mix that drew both Kentridge and Berg to Büchner, and has now in turn drawn Kentridge to Berg at this moment in Kentridge’s layered generative journey.

Kentridge’s Wozzeck set

Q & A with Mike Ledermueller: Technical Director, Canadian Opera Company

WN: Looking at images from the Salzburg production, this doesn’t look like a set that clips together right out of the containers!

ML: It definitely brings with it a unique set of challenges that make its installation and shipping more complicated than a traditional opera set because it was born out of a very organic creation process. The “Island” of the set – the risers and scenery that make up the central stage, is made of stock scenery plus found elements from the Salzburg Fest spiel and surrounding area. These pieces were then stacked, and sculpted to give us what we have today, but with various alterations throughout its life on the road. Traditionally, an opera set will have a clear system of assembly and an intuitive method to go together, and with crating and carting engineered for efficient loading, unloading, assembly and storage. This is a literal pile of old bits.

So how do you go about it?

Thankfully over its lifetime, our colleagues around the world have taken documentation photos and labelled the scenery to know which pieces attach to what. We likened the build process to assembling a large jigsaw puzzle with no edge pieces. This means a lot more time sorting through everything to find the part you need next. Where a set of this scale would normally take us about 4-8 hours to assemble the first time, this took us about three days.

With all the different media involved, is it a demanding show to run?

Actually, after assembly the show is quite straightforward, with video being the most complicated part. The original video for this piece was more like a character in the show, with the designer and operator adapting to the varying tempi and cast’s gestures, rather than a rigid cued playlist. Again, with the evolution of the work, we’ll be striving to keep the process manageable by our crew here at the FSC – maintaining original intentions of each moment, but within the confines of our playback system.

This looks like a tough set for the cast to negotiate.

It is. Particularly tough. Given the shape of this set with all of its rakes(slanted floors), levels, duckboard and steps, it’s imperative the cast have the time on the set to safely learn how to navigate the “Island” – with extra precautions in place at first, before we take the training wheels off.

Kentridge talks about about how charcoal changed his way of working – the capacity for endless erasures: draw, capture, erase, add, repeat. Does he make opera the way he uses charcoal?

Yes. I think that plays out clearly in the projections. Separate from the “Island” is what is sometimes called the “Landscape”, the large rear screen. This gives him the ability to flash through several of his drawings throughout the show to match with each scene. The structure of Wozzeck in particular lends itself to that idea as it’s a series of separate scenes, not a flowing journey, almost like pages in a sketch book. Not to mention, slightly transposing the time to WW1; the grit, dust and smudging of charcoal clearly lends itself to imagery we see of that time. Such a blunt, dark medium, strongly evoking the destruction of a Passchendaele or Sommes battlescape.

David Perlman can be reached at publisher@thewholenote.com