It’s hard to believe five years have passed since “the little Oundjian that could,” as one WholeNote reader affectionately dubbed him, chugged into town. His contagious energy continues unabated. Case in point: every September since 2005, the Toronto Symphony Orchestra has taken its show on the road, to Northern Ontario, for a five day “residency tour.” Thanks to cellphones, I caught up with him anyway.

It’s hard to believe five years have passed since “the little Oundjian that could,” as one WholeNote reader affectionately dubbed him, chugged into town. His contagious energy continues unabated. Case in point: every September since 2005, the Toronto Symphony Orchestra has taken its show on the road, to Northern Ontario, for a five day “residency tour.” Thanks to cellphones, I caught up with him anyway.

So where are you this time?

Oundjian: En route from Sudbury to Sault Ste. Marie and it’s an absolutely glorious cloudless day.

Not doing the driving I hope?

Oundjian: No I’m sitting beside the person who organized the tour [Roberta Smith]. She drives like Stirling Moss by the way, so we have to speak fast … we’re only 200km from Sault Ste. Marie!

How many musicians on tour?

Oundjian: Fifty-five to sixty, something like that, we’re doing some fairly big pieces, the Mendelssohn “Italian,” a bit of Carmen, a big new piece by Gary Kulesha … so sixty I would say.

For how long?

Oundjian: We came up Monday and had a concert last night [Tuesday] in Sudbury for a wonderful public. This morning, two youth concerts for school children, tomorrow a school concert in the morning and a public concert in the evening, then Friday morning another school concert and then we go home.

Five years ago you were in Connecticut about to hit the road for here, first time as music director. We talked quite a bit about the differences between your anticipated roles as music director and as conductor. Do you see that distinction differently now, or have the two roles tended to merge?

Oundjian: It’s an interesting question and slightly difficult to answer in that I don’t quite remember how I felt about it back then (laughs). When you start with an orchestra, they have an idea of you as a conductor, because they’ve obviously seen you rehearse and perform a number of times in order to decide to invite you to be their conductor. But they haven’t yet discovered what approach you take as an artistic leader, in terms of programming, but maybe more particularly in terms of how you handle personnel issues – the kind of effect you might have on morale.

You’re right, though, that after five years those two roles grow much more together. They understand how I think in a more general way as a human being … For me I think I feel quite relaxed about the way those two aspects of the role have come together. I very much enjoy working on all the aspects – especially of course on the music.

Five years ago, you talked about how the personality of the music director emerges through such things as getting to hire players for a particular style and a sound… .

Oundjian: That’s very interesting to reflect back on now. At the time, I had probably hired two people and they hadn’t even started yet, and now I’ve probably hired fifteen to twenty. I’m not sure if it’s even healthy for me to try to define what I’m looking for. It’s like asking “what are you looking for in a great poet, or a great painter?” It’s not an equation – there is something in the characteristics of a musician that speaks to one. When it happens, it is suddenly very clear that this is somebody who is on the same page, speaks the same language as I do and as I feel the orchestra does… And yet to say what that is, I’m not even sure I’d want to.

Looking at the current season, are there things you can point to and say “there, that concert or that particular strand of things, that’s what I’m trying to do, that’s my stamp."

Oundjian: I can think of quite a few, maybe starting with the Britten War Requiem, which I have been longing to do with the TSO, because I met Britten about three years after the piece was first written and recorded. I think you know that story of how I was a boy soprano and made a few recordings with Britten conducting. Particularly on Remembrance Day to do the War Requiem is veryspecial.

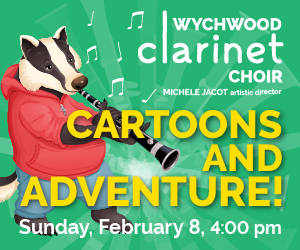

A lot of the programmes this fall are very close to me. For example, Vaughan Williams’ 4th Symphony … I champion the Vaughan Williams symphonies, take them to many other orchestras all over the world. But this particular TSO programme [October 21, 22, and 24] also features Joaquin Valdepeñas ‑ the 30th anniversary he has been playing with the TSO, and I wanted to mark that anniversary, so I’ve given him the entire first half. He’s doing an arrangement of the Bernstein Sonata, and the Mozart Clarinet Concerto which is his choice. That’s a kind of programming that I love.

And more than those two even, I’d say look at December, where you have a programme from my very old friend, the wonderful fiddle player Robert McDuffie, who has been talking to me for probably five years about Philip Glass writing him what was originally intended to be a 21st century Four Seasons. That programme starts with a piece by a wonderful American composer, Chris Theofanidis, called “Rainbow Body” and then we do Beethoven’s “Pastoral,” featuring all these images of nature, of course the storm and so on. And then the Glass.There is kind of a relationship between the pieces, a running thread, but it is quite free, and there is an incredibly wonderful contrast between all the pieces.

Also, the festivals that we started, that you and I must have also spoken about five years ago, have taken on a life on their own – the Mozart festival, I mean I intended for it to go on for Mozart at 249 and Mozart at 250 and that would be it. But now we’re at Mozart at 254 and I’m not allowed to stop. And the New Creations festival took a couple of years to really work out, how to give it the energy that it deserves. We’ve come to a formula where we give only one performance of each programme. It gives us much more time to rehearse each programme, which is great, and it continues to attract every composer featured. Golijov is in residence this year, and there are a lot of very interesting other composers coming in.

So these are a few things that have a bit of my identity on them. I’ve always felt that in a way you don’t want to have too strong of an identity because then you can’t be eclectic. But you don’t want to be a conductor who is known to be just really good at everything because then you would not probably be considered to be great at anything. (I don’t think about this too much, by the way, except probably when you and I are talking.)

The truth of the matter is that when I’m standing up and conducting Bruckner there is only one thing in my life for that hour and a half, probably for the previous weeks in fact, and that is understanding the character of the music as deeply as I can.

What about the differences between being TSO resident conductor and being a guest conductor – are you getting busier as a guest conductor?

Oundjian: It’s been fairly consistent – I’m going to more orchestras – I’ve cut back on some a little bit so I have more time. Certainly next season I’m going to Europe much more, and this season I’m conducting Chicago for the first time in several years, and I have a fairly regular relationship with a lot of orchestras like Philadelphia and San Francisco. It’s wonderful when you know the players and the institution quite well because you feel not as a guest who has to be on your best behaviour.

Do you find yourself being pigeon-holed in terms of repertoire – oh, let’s get Oundjian for that one.

Oundjian: I have to do different repertoire every week, it seems like. I seem to be asked to do everything from Mozart and Haydn to contemporary pieces, or a piece like Carmina, Brahms, Shostakovitch, Mahler. It’s a very broad cross-section and I guess I should be very grateful that I haven’t been pigeon-holed particularly.

Oundjian: I have to do different repertoire every week, it seems like. I seem to be asked to do everything from Mozart and Haydn to contemporary pieces, or a piece like Carmina, Brahms, Shostakovitch, Mahler. It’s a very broad cross-section and I guess I should be very grateful that I haven’t been pigeon-holed particularly.

A totally other topic, we talked about video screens at concerts five years ago, and you were very definite about not liking them. Have you changed your mind on that one?

Oundjian: Well, in Sudbury yesterday there were video screens up on the wall and they were about half a second delayed. So if I would look at myself on the video I couldn’t follow myself. So here’s where I am with it today: occasionally it can be very engaging, if it’s really skillfully done. And absolutely they have to make it instantaneous. Because when there’s a very slight delay I find it’s just strange. If you look at the video it looks like the conductor’s lagging. And if you look at the players on screen and you’ve already heard the sound they’re making, it’s very weird. So you’ve got to deal wit that.

The important thing is that we leave the music up to the imagination, and that the sound itself should remain the predominant message. I think that doing stuff with video is very healthy, but I still think that the lion’s share of what we need to do should be very pure. I don’t want to mistrust the music and suggest for a moment that without visual aid it’s inadequate in some way.

Speaking of mixing and matching in programmes, some of yours that I’ve enjoyed the most have been all one composer, Brahms, for example. That can also be surprisingly satisfying.

Oundjian: Yes, exactly; having just spent an entire evening living in that composer’s world. I think it comes back to what I said about being eclectic. If every one of my programmes was trying to contrast, or create a thread that was similar, I might be able to come up with limitless ideas on that basis. But if I’m using the same basis all the time, maybe that becomes trite and boring.

Later on this season we’re doing a complete evening of Mendelssohn with Itzhak Perlman, with the Violin Concerto, “Italian” Symphony and the “Hebrides" Overture

On the other hand, I did a programme last year which was a little bit of Peer Gynt and the Brahms Second Piano Concerto, and then, more Scandinavian, the Nielsen Fifth Symphony. But we did the Neilson after the Peer Gynt, and left the Brahms concerto for the second half. Now people might have said, well, that’s kind of weird, why is the symphony first? But I say, first of all, you know, it’s not bad to change things up. I don’t want people to think, well you know I just heard Yefim Bronfman play the Brahms and that was so satisfying, and I don’t know if I like Nielsen, so you know, I’ll go home and have a bite to eat. I hate to be so practical but I really do think that way. So there are always different reasons for creating a programme and the order of that programme.

When you described the special October concerts featuring Joaquin Valdepeñas I wondered what an equivalent Oundjian tribute concert might consist of, somewhere down the line? Can you think of a programme?

Oundjian: I hear you very clearly and I’m shaking in my pants at the thought. I think it would be so painful because there are so many wonderful people who I would want to invite to take part in such an event, let alone choosing the programme. Even not to do a piece by Alban Berg would be painful. I think my answer is I don’t think I could ever do it because it would become more about elimination than about doing things that I love the most. Probably any conductor in my position would say the same thing. I’m hoping to have the wisdom never to do that.

Aha, but it’ll be done to you!

Oundjian: Then I’d probably say you choose the programme, and just make sure everyone knows that I didn’t.

Last question. Looking back at the five years, what’s been harder to accomplish than you thought it would be, and at the other side, what has exceeded your expectations?

Oundjian: I think I’m a person who doesn’t get addicted to expectations. Life is never what you expect it to be. Maybe it’s because of what I went through with my violin playing. I never obviously expected that somewhere in my late thirties I would suddenly not be able to play the violin anymore, so it’s made me have a very free approach to expectations. So I must say I don’t get particularly perturbed by things, or even necessarily remember if things don’t go the way I was hoping. I’m realistic enough to know you’ve got to expect there to be obstacles to your life’s work and to the progress of a large institution…. Sounds like an optimistic response but that’s genuinely how I approach it.