While researching this piece, I stumbled across this comment by John Terauds (founder and first editor of the blog Musical Toronto, now Ludwig van Toronto). “Earlier this year, we needed to pity Argentinean composer Osvaldo Golijov as he was attacked for quoting other composers’ music in his own,[but] if we only look back two to three centuries, we find composers borrowing, quoting and parodying themselves and each other — proving that imitation once was the sincerest form of flattery.”

While researching this piece, I stumbled across this comment by John Terauds (founder and first editor of the blog Musical Toronto, now Ludwig van Toronto). “Earlier this year, we needed to pity Argentinean composer Osvaldo Golijov as he was attacked for quoting other composers’ music in his own,[but] if we only look back two to three centuries, we find composers borrowing, quoting and parodying themselves and each other — proving that imitation once was the sincerest form of flattery.”

The comment came in a 2012 review of a just-released recording of six concertos composed by University of Montreal Early Music specialist Bruce Haynes, who had died the previous year. Although “composed” is not exactly the right word.

The comment came in a 2012 review of a just-released recording of six concertos composed by University of Montreal Early Music specialist Bruce Haynes, who had died the previous year. Although “composed” is not exactly the right word.

Haynes, in Terauds’ words, “had scoured 13 of Johann Sebastian Bach’s cantatas, the Mass in G Minor and the Concerto for 3 Harpsichords in D Minor for material he could adapt into a set of six concertos in the style of the six original Brandenburgs. … [and] Eric Milnes and the period-instrument Bande Montréal Baroque … including Haynes’ widow, gamba master Susie Napper turned it into glorious sound only a couple of weeks after his death.”

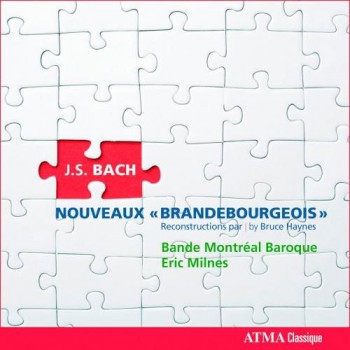

The recording was released by ATMA Classique under the title Nouveaux “Brandebourgeous” Reconstitution/Reconstruction.

The recording was released by ATMA Classique under the title Nouveaux “Brandebourgeous” Reconstitution/Reconstruction.

Brandenbourgeous, indeed: We’ll be hearing the final one of these six Brandenbourgeous “reconstitutions” at this year’s Toronto Bach Festival — Brandenburg Concerto No.12,as TBF is calling it in their literature. But it’s not there as an oddity. More like a musical keynote address for the whole festival, first work in the festival’s Friday night opening concert, titled “Brandenburg Reimagined”.

“Bach re-imagined is not a new idea,” proposes oboist John Abberger, TBF’s Artistic Director. “Bach went about reimagining Bach all the time. Revising and revisiting himself, an inveterate miner of his own work, reusing bits like crazy. And that’s kind of my point of departure for this year’s festival.

“Bach re-imagined is not a new idea,” proposes oboist John Abberger, TBF’s Artistic Director. “Bach went about reimagining Bach all the time. Revising and revisiting himself, an inveterate miner of his own work, reusing bits like crazy. And that’s kind of my point of departure for this year’s festival.

“To me, this is what a Bach festival should do – play these things that you’re not going to hear very often, or contextualized like this, in the regular rest of the year.”

Seen through this lens, the program for the May 30 opening concert has an imaginative unity greater than the sum of its parts. Haynes’ Brandenburg 12, drawn in its entirety from the congregational intimacy of three of Bach’s sacred cantatas (BWV 163, 80, and 18) opens the concert, The intimate richness of Brandenburg No.6 draws it to a close.

Every note of Haynes’s reconstitution is pure Bach, but Abberger confesses to “tweaking things a little bit, with Susie Napper’s blessing, so as to emphasize even more Bruce’s conception of the piece as a kind of doppelganger of the sixth Brandenburg. Bruce’s was a piece for four gambas. And I thought, well, wouldn’t it be interesting if you could make that two violas and two gambas, just like Brandenburg No.6. So we did, and we changed the key to make it work”

The middle two works on the Friday evening program evoke the same “sounds familiar but” feeling that the outer works do. “They are Bach’s own re-use of Brandenburg Concerto No.4 in a thrillingly intimate version for harpsichord, with our beloved Christopher Bagan as soloist. And another harpsichord concerto will be heard, in its probable original form, as a soaring violin concerto, with Julia Wedman as soloist,” Abberger says.

Lautenwerk: “One swallow doth not a summer make” as the saying goes. Similarly one should not assume that a festival’s opening concert necessarily sums up the festival. But in this year’s TBF, “strangely familiar” easily transposes to the Saturday.

Lautenwerk: “One swallow doth not a summer make” as the saying goes. Similarly one should not assume that a festival’s opening concert necessarily sums up the festival. But in this year’s TBF, “strangely familiar” easily transposes to the Saturday.

One of the constants of TBF’s Saturday has been a midday recital that explores all of Bach’s keyboard music over time. It typically switches between organ and various precursors of the piano in alternate years.This is a “piano precursor” year, and this year’s instrument is the lautenwerk – a kind of lute-harpsichord.

“We know Bach owned two of these instruments, but none of them have survived into the 20th century. Dongsok Shin, this year’s keyboard artist is a friend of mine for many, many years, back to my New York days,” Abberger explains. “He is an expert on historical keyboards, and the instrument he will be playing is a replica built to his needs and wishes. It doesn’t look much like the sketch you’ll find of a Bach era instrument, which looks like a giant lute on its side, but it’s absolutely gorgeous, and the sound is ravishing.”

True to our reconstitutional theme, the repertoire for the recital draws on a wide range of Bach’s music, including works written for lute and for harpsichord, and more, including a sonata for harpsichord and oboe which gives Abberger the opportunity to get into the action.

Kaffeehaus: Saturday’s other event, the Kaffeehaus, was a relatively late addition to TBF, and has moved around a bit, but is now well and truly entrenched in the welcoming downtown surrounds of Church of the Holy Trinity. New this year is an extra show at 8pm for this increasingly popular festival centrepiece.

“Join us again for our acclaimed Kaffeehaus concert, as we continue to explore Bach’s secular vocal music, headlined by his Wedding Cantata, as well as instrumental gems by Bach and his contemporaries in the spacious acoustic of the Church of the Holy Trinity which will be transformed for our recreation into an 18th-century Leipzig coffee house” proclaims the TBF website.

But if it’s a reconstituted 18th century coffee house, you don’t know for sure who will come through the door, or what you will hear. Other than that, in the spirit of the time, you’d have been most likely to observe (as John Terauds described it earlier), “composers borrowing, quoting and parodying themselves and each other. Imitation … as the sincerest form of flattery.”

Especially, in Bach’s case, when imitating himself.

The Passion(s) of St. John: There is an obvious usefulness to readers in describing a three-day event in chronological order. But Sunday’s “big finish” St. John Passion, with visiting director and Bach Scholar John Butt at the helm, would have been as good a place to start in terms of the overarching construct of the festival. In the festival’s annual Sunday lecture (same venue, Eastminster United, as the performance but with time enough between to stroll the Danforth), Butt will talk about Bach’s creative process with particular reference to the St. John Passion, which survives in no fewer than four distinct versions. This performance will be the 1725 second version, which has striking differences from the 1724 version – the one you’re most likely to hear performed.

The Passion(s) of St. John: There is an obvious usefulness to readers in describing a three-day event in chronological order. But Sunday’s “big finish” St. John Passion, with visiting director and Bach Scholar John Butt at the helm, would have been as good a place to start in terms of the overarching construct of the festival. In the festival’s annual Sunday lecture (same venue, Eastminster United, as the performance but with time enough between to stroll the Danforth), Butt will talk about Bach’s creative process with particular reference to the St. John Passion, which survives in no fewer than four distinct versions. This performance will be the 1725 second version, which has striking differences from the 1724 version – the one you’re most likely to hear performed.

“It has a different opening chorus, and a different closing chorus,” Abberger says. “Well he actually retains the famous closing chorus but adds another, something that he’d previously tacked on to one of the cantatas that he played as his audition piece when he applied for the position of Thomaskantor director of church music in Leipzig, which would have been, hmm, in February 20, 1723, and it’s a fantastic piece. The new opening chorus shows up later, by the way, in the St. Matthew Passion …”

We’ll have to wait another year to see where that idea takes him!