Please click on photos for larger images.

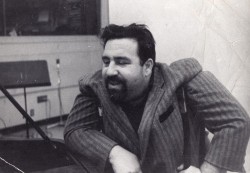

AKA Doc Pomus, which opened November 29 at Cineplex Yonge and Dundas, is a befitting memorial for its subject, the legendary songwriter and genuine mensch, Doc Pomus. On braces and crutches after being stricken by polio at six in 1931, Jerome Felder (his birth name) loved listening to African-American music on the radio growing up in Brooklyn. His epiphany came around the age of 15, with Joe Turner’s record of “Piney Brown Blues.” Two years later he talked his way onto the stage of George’s in Greenwich Village. As he put it, “I was a white boy hooked on the blues – it was a midnight lady with a love lock on my soul.” After a handful of years, his recording career ended but by then Joe Turner himself had heard him and told Ahmet Ertegun to hire Pomus. Doc became a songwriter, one of the cornerstones of the legendary Brill Building writing for Turner and many more.

AKA Doc Pomus is a straightforward biography told by ex-wives and lovers, sons and a daughter, musicians and writers (Peter Guralnick and Dave Marsh, most notably) and adding even more to the many candid moments of archival footage of the man, there is Lou Reed on the soundtrack reading from Doc’s journals.

The songs speak for themselves: “Lonely Avenue” (for Ray Charles); “Save the Last Dance for Me” (inspired by Pomus’ own wedding and immortalized by Ben. E. King); “Why Must I Be a Teenager in Love” a piece of South Bronx blues encapsulated by Dion and the Belmonts (Bob Dylan said that everything you need to know is in that song). He wrote with Phil Spector and Mort Shuman, wrote big hits for Elvis (“Viva Las Vegas” and a host of movie vocals – when the King was under contract with MGM to make four musicals a year, each with ten songs) and Andy Williams (“Can’t Get Used to Losing You” taken from his own marriage breakdown). He worked with Dr. John, championed Lou Reed and little Jimmy Scott and taught Shawn Colvin and Joan Osbourne in his songwriting course. Dylan asked to write with him; John Lennon was a fan who became a friend. He was a denizen of midtown Manhattan hotels, the centre of revolving, seemingly never-ending musical evenings.

Doc Pomus’ song ended in 1991; AKA Doc Pomus reminds us that the memory lingers on. His life was a work of art of his own creation.

When you’re lost in Juarez these days, you’re in the murder capital of the world (3622 in 2010, for example – El Paso, Texas across the Rio Grande had five that year). Shaul Schwarz’s Narco Cultura is a cinéma vérité look at the Mexican drug cartels’ pop culture influence on a narco corrido singer, Edgar Quintero, with stars in his eyes and bullets in his belt, set against a crime scene investigator who must mask his identity to protect his life in Juarez. The singer makes the brutal life of a cartel member glamorous; fans on both sides of the border eat this stuff up. One journalist puts it in perspective: “Narcos represent limitless power but they are a symptom of a dead society; 92 per cent of murders have not been investigated.” Quintero takes a trip to Culiacán, in the heart of the northwestern state of Sinaloa. Schwarz follows him into a beautiful cemetery with big tombs filled with young dead men. Schwarz’s camera indicts without prejudice making for compelling viewing. Narco Cultura, which premiered in May at Hot Docs, returns to the Bloor Hot Docs Cinema for a brief run, November 29, 30, December 1 and 5.

The Broken Circle Breakdown, a bluegrass musical and Belgium’s nominee for consideration as Best Foreign Language Academy Award, recently finished its brief engagement at TIFF Bell Lightbox. This lovely film tells the story of Didier, a banjo-playing farmer, Elise, his tattoo parlour worker wife, their six-year-old daughter Maybelle and her battle with cancer. The narrative begins by flashing back seven years to the couple’s first meeting and their intense love for each other, which never ebbs.

Didier is enamoured of the settlers of the Appalachian Mountains, the dirt-poor fortune hunters who lived there mining the slate that was so difficult to crack. To combat their hunger and misery -- he seduces Elise with this story actually – they sang about their dreams of a promised land, about their sorrow and their hunger and their misery, their fear of dying and their hope for a better life. As Didier tells it, each immigrant group brought a specific instrument to the mix: the Spaniard, a guitar; the Jew, a violin; the African, a banjo; and the Italian, a mandolin. It’s the essence of folk music according to Didier and Bill Monroe, the father of bluegrass, is the greatest musician in the world.

As the movie moves forward (and backward with its many flashbacks) we realized that it’s a country song come to life. Several country songs, in fact, in which love, joy, grief and blame play major parts, but the music is always tunefully sweet. Didier plays banjo in a classic bluegrass quintet; Elise becomes the lead singer and their performances punctuate and comment on the narrative, none more appropriate than Townes Van Zandt’s “If I Needed You.” Watch for The Broken Circle Breakdown at a rep theatre or on video. It will take you to “the glory land.”

Two other films now playing are worthy of attention. Philomena, the runner-up to 12 Years a Slave for the People’s Choice Award at TIFF 2013, benefits from an Oscar-worthy performance from Judy Dench, a rich screenplay by Jeff Pope and Steve Coogan (who co-stars), a sensitive score by Alexandre Desplats and the remarkable Stephen Frears, who directs without show or artifice but always in the service of the humanism of the film’s riveting, true story.

Dench plays the title character, a retired Irish Catholic nurse whose pangs of regret, guilt and curiosity well up on what would have been her son’s 50th birthday to push her to find the child who was taken from her when she was under the care of the Abbey Sisters of Sacred Heart in Roscrea, Ireland as a teenager in the 1950s. Her companion in this search is a high-profile Oxford-educated ex-BBC television journalist and political scapegoat (played to acerbic perfection by Coogan). As the plot thickens, Desplats’ music (performed with subtlety and warmth by the London Symphony Orchestra) intensifies but never oversteps its bounds. The late John Tavener’s “Mother of God Here I Stand” makes a moving appearance near the end of this first-rate film that sensitively explores the bonds of maternal love, and the many facets of faith. Philomena opened November 29 at the Varsity and other theatres.

Short Term 12 follows foster children in a treatment facility being cared for by former foster children who have overcome the kind of problems that have led their patients into the bungalow they now call home. These are teenagers, mostly, who have been abused or who could not find comfort in their previous domestic life. Thoughtful and compassionate, it’s no docudrama, but a powerful story of parallel lives, propelled by a tour de force of realistic acting (Brie Larson, Best Actress, Locarno Film Festival 2013).

Larson plays Grace, a counsellor whose memories of an abusive childhood experience are unlocked by a new patient, Jayden (Kaitlyn Dever). The staff’s regular modus operandi is to use empathy as a major tool of therapy, so it’s doubly intense when Grace makes it so personal with Jayden.

The movie begins and ends with anecdotes by Mason, Grace’s fellow counsellor and boyfriend, the second of which sends you walking out of the theatre on a high since it reveals a crucial piece of information about another patient who we’ve come to root for.

Joel P West’s instrumental soundtrack is minimal and serviceable but his songs and especially those rapped by Keith Stanfield (who has a key supporting role in the film) deepen the authenticity portrayed onscreen. Short Term 12 is playing at TIFF Bell Lightbox and the Carlton.