Like many in the global village, I have become a fan of the Metropolitan Opera’s LIVE from the Met in movie houses, combining as it does all the lazy pleasures of movie going (a director telling you where to look, a soundtrack telling you what to feel) with an almost voyeuristic immediacy. I am behind the scenes of one of the world’s great opera houses, or face to face with the four feet tall tonsils of the world’s greatest bass-baritone, as the case may be. Add to this usual movie stuff the additional thrill, usually reserved for NASCAR or other such blood sports, of knowing that the whole thing might crash and burn right before my eyes, but almost never does, and I am hooked. Why? Because it’s LIVE!

Like many in the global village, I have become a fan of the Metropolitan Opera’s LIVE from the Met in movie houses, combining as it does all the lazy pleasures of movie going (a director telling you where to look, a soundtrack telling you what to feel) with an almost voyeuristic immediacy. I am behind the scenes of one of the world’s great opera houses, or face to face with the four feet tall tonsils of the world’s greatest bass-baritone, as the case may be. Add to this usual movie stuff the additional thrill, usually reserved for NASCAR or other such blood sports, of knowing that the whole thing might crash and burn right before my eyes, but almost never does, and I am hooked. Why? Because it’s LIVE!

Except that it isn’t. It’s “live from,” but not live at. At, in this case, is the Queensway Cineplex Odeon, TimBits, mint tea and all. Even the Met’s celebrity greeters acknowledge as much. One of them always comes on screen during one or the other intermission, backstage, to remind us, the TimBits audience, that watching this way isn’t the real thing, and that to fully experience the magic of opera we should pop down to New York, or [tiny pause] go out and support our local opera company. My most recent foray to the Odeon was for an enormously satisfying production of Phillip Glass’s Satyagraha, during which bass baritone Eric Owens (Alberich in the Met’s current Ring Cycle) appeared during the intermission to do the mandatory “live opera is real magic” speech. Even in his sonorous tones it came off stilted and, dare we say it, just a titch insincere.

More’s the pity, because it’s the absolute bottom-line truth. There is an innate, unmatchable theatricality in congregating live for music. It cannot be matched or emulated in other media, no matter how grand. And nowhere is this more evident than in the performance of new music.

Ironically, the first performance I want to draw to your attention, as an example of theatrical spectatorship, seems to negate that principle, because, to a significant extent, it takes place in the pitch dark. I heard about it from composer Brian Current, director of the New Music Ensemble of the Glenn Gould School. The work is Austrian spectral composer Georg Haas’ monumental In Vain, for 24 musicians and lighting (2000) Thursday December 8, 7:30pm and Friday December 9, 2:30pm, in the Conservatory Theatre of the Royal Conservatory.

“It’s a 70 minute piece, really a spectral wonder, a beautiful and substantial work, based almost entirely on musical colour,” Current says. “Sometimes they play in the pitch black, other times there are ghostly flashes of light.” They will be blocking the windows out on the Conservatory Theatre to get complete darkness. “The ensemble is all graduate students and they have been working hard on this difficult material, even memorizing the portions in the dark. We are also very fortunate that GF Haas is also coming in for these shows from Austria, just to work with us and to deliver a talk at 6pm before the Saturday performance.”

As it happens, the two In Vain performances fall slap bang right in the middle of what is undoubtedly December’s new music main event (the Vinko Globokar invasion, November 29 to December 11) so here’s hoping it won’t be overlooked. After all, somewhere in the tranformation of noises in the night to sounds in the dark, the truly theatrical nature of music has its beginnings.

By contrast, Queen of Puddings Music Theatre’s presentation of Galgenlieder à 3 (Gallows Songs) by Sofia Gubaidulina affirms its theatricality quite explicitly, billing itself as “a concert drama.” Queen of Puddings has always had an aesthetic of physical, singing theatre, going all the way back to their first production, “Mad for All Reasons” in 1996, which was built around Peter Maxwell Davies’ Eight Songs for a Mad King. Part of that aesthetic is curatorial, latching onto music that has an intrinsic theatricality rather than adding visual cheap tricks to jazz up the musically ordinary.

Gubaidulina’s Galgenlieder fits the bill. “It’s a 15-song cycle — sung in the original German — featuring the text of German poet Christian Morgenstern (1871–1914)” says Dáirine Ní Mheadra, QoP co-founder and director. “Gubaidulina’s stature in the world of contemporary music is enormous — she is one of the pre-eminent composers alive today. Her music is dramatic and intense.”

Born in Christopol in the Tatar Republic of the Soviet Union in 1931, Gubaidulina’s music was an escape from the terrifying socio-political atmosphere of Soviet Russia, Ní Mheadra says. “For this reason, she associated music with human transcendence and mystical spiritualism. Bringing these qualities plus a wicked sense of humour to her settings of Morgenstern is a knockout combination. And to have a star singer like Betty Allison singing this Galgenlieder is sumptuous. Betty’s sound has voluptuousness and an emotional depth to it that is profoundly moving.”

From Ladysmith, BC, by way of the Canadian Opera Company ensemble, Allison has been exercising her new music “chops,” coming to town hot off the title role in the Pacific Opera premiere of Mary’s Wedding (music Andrew P. MacDonald, libretto Stephen Massicotte.) In Galgenlieder she shares the stage with Ryan Scott, percussion, and Joseph Phillips, double bass, both accustomed to swimming outside of the mainstream as well as in.

Phillips, a former student of “tune ’em in fifths” bass virtuoso Joel Quarrington, has made frequent appearances with Art of Time Ensemble and is a member of Hotland Trio, a moody Balkan/Canadian trio (with violinist Aleksandar Gajic and accordionist Milos Popovic) that brings serious classical muscle to moody, driven, strongly rhythmic repertoire.

And Ryan Scott is one of the most versatile, accomplished (and busy) percussionists in this or any other town. Case in point, he will take the stage for Galgenlieder a week after a scorching performance of 20th century Japanese percussion titan Maki Ishii’s South-Fire-Summer for Esprit Orchestra at Koerner Hall November 30 — a work of extraordinary complexity requiring a percussion array the size of (and better stocked than) the average kitchen. And just one day later, December 9, it will be out of the proverbial frying pan into the improvational fire for Scott, as he anchors the second half of the first of the two Vingko Globokar concerts to which I referred briefly at the beginning of this column and to which I now return.

And Ryan Scott is one of the most versatile, accomplished (and busy) percussionists in this or any other town. Case in point, he will take the stage for Galgenlieder a week after a scorching performance of 20th century Japanese percussion titan Maki Ishii’s South-Fire-Summer for Esprit Orchestra at Koerner Hall November 30 — a work of extraordinary complexity requiring a percussion array the size of (and better stocked than) the average kitchen. And just one day later, December 9, it will be out of the proverbial frying pan into the improvational fire for Scott, as he anchors the second half of the first of the two Vingko Globokar concerts to which I referred briefly at the beginning of this column and to which I now return.

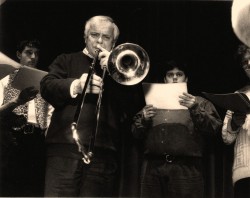

Vinko Globokar, French avant-garde composer and trombonist, returns to Toronto at the invitation of New Music Concerts’ artistic director Robert Aitken, almost forty years (1972) after Aitken brought him here in the first place.

He’s been back in between, but this is a 12-day Vinko-fest, culminating Sunday December 11, at Betty Oliphant Theatre, 8pm, in an NMC presentation of works spanning four decades, ranging from Fluide (1967) for brass and (very extended) percussion through Eppure si Muove (2003) for solo trombone (Globokar) and an ensemble of 11 disparate instruments including cimbalom, accordion, saxophone, synthesizer and electric guitar, without conductor. In between are Discours VII (1987) for brass quintet, which “attacks problems posed by spatialisation of sound, mobility of sound sources and different degrees of communication between five people,” and Eisenberg (1990) for four groups of four: brass instruments ad libitum (such as Tibetan horn, Moroccan nafir, conch), melodic instruments, harmony instruments and musicians who work with noises (unspecified percussion).

Even this mere recitation of ideas and instrumentation gives a tiny taste of the infinite variety, and jest, of this pioneer of modern trombone technique. Quite simply this is an individual who never repeats himself compositionally or artistically, challenging audiences and players (be warned, they are not always entirely distinct!) anew with every new outing and every new work.

Events in his visit will already be under way by the time this issue hits the street: at the University of Toronto, where Globokar is the Michael and Sonja Koerner Distinguished Visitor in Composition — improvisation workshops, forums, lecture, and a Globokar Colloquium at the Robert Gill Theatre. The following week Globokar will work extensively with the musicians of the New Music Concerts Ensemble and give masterclasses and improvisation workshops through the auspices of the Music Gallery. Some of the results of all this activity will be on display at the Music Gallery, Friday December 9, in the first half of the concert, titled “Back to Back.” The second half of that concert is an extended music/theatre piece Terres brulées, ensuite … co-presented by Toronto New Music Projects and Continuum, which bring me back to percussionist Ryan Scott.

Earlier, you may recall, I mentioned that, for Scott, going from Galgenlieder on December 8 to Globokar at the Music Gallery the next day would be like going from frying pan to fire. Here’s how he described it (in the Continuum Contemporary Music November newsletter).

“After intermission is the epic Terres brulées, ensuite … (Burned Lands, Then …). Prepare for global annihilation! This trio for saxophone, piano and percussion featuring Wallace Halladay, Stephen Clarke (piano) and myself, is of legendary proportions and is rather difficult to describe: 6 saxophones, a prepared (and lightly abused) piano, over 70 percussion instruments (e.g. #43 “plank”) spread around the stage in 7 stations, 115 performance instructions (e.g. #21 Saw the plank and hammer in a nail), … live electronics … What else? Hmmm … a motet … a foghorn … oh, and explosions with fire (well, we’re working on that).”

There’s a wonderful interview with Globokar by British composer John Palmer available on the website of the Canadian Electroacoustic Community. For the curious it’s a great place to start.

What I got from it was the sense of energetic decades of musical inquiry, endlessly parsing and reparsing the relationships between music and speech, and rendering into music the theatricality of relationship. Part of his secret, I suspect, is a thick skin, the ability not to judge his own work in terms of success or failure. As he puts it:

“What is sure is that a musical work is a document which will remain. It’s a document that testifies certain things that happened at a certain time in society. This is an historical truth which cannot be denied. In one hundred years people will say, ‘This music reflects certain events that happened in those years.’ … L’art pour l’art as such does not interest me, at all.”

AND ALL TOO BRIEFLY

“Beyond Sound,” the 2012 iteration of the annual New Music Festival at the University of Toronto Faculty of Music, coordinated by composer Norbert Palej, features Swedish composer Anders Hillborg as the Roger D. Moore Distinguished Visitor in Composition and runs from January 22 to February 5. It’s billed as an exploration of “the diverse scientific and artistic interests that form the musical landscape of the 21st century,” with a focus on Hillborg’s work. It’s an event warranting much more of a mention than this. Happily, it’s well covered in our concert listings, and in “The ETCeteras” (page 67), our regular compilation of musical workshops, forums, lectures, etc. It is also very well described on the Faculty’s own website under “Events.”