On the evening of Sunday, February 13, a friend and I met for dinner at a popular Italian restaurant at Bloor and Lansdowne. As we were seated, a glance at a muted, wall-mounted television informed us that our incipient pasta consumption coincided with something called the Super Bowl. As members of overlapping artistic communities in Toronto, we were, perhaps predictably, caught unawares. Like us, most of the restaurant’s clientele was more interested in tagliatelle than touchdowns, and the volume stayed off – at least until the halftime show. Suddenly, 50 Cent, Snoop Dogg, Mary J. Blige and a host of other performers took the field. A glance at the menu revealed a surprising throwback drink: an espresso martini. From a neighbouring table, a conversation drifted over, bemoaning the quality of the new Sex and the City show. It was official: we were back in the 2000s.

On the evening of Sunday, February 13, a friend and I met for dinner at a popular Italian restaurant at Bloor and Lansdowne. As we were seated, a glance at a muted, wall-mounted television informed us that our incipient pasta consumption coincided with something called the Super Bowl. As members of overlapping artistic communities in Toronto, we were, perhaps predictably, caught unawares. Like us, most of the restaurant’s clientele was more interested in tagliatelle than touchdowns, and the volume stayed off – at least until the halftime show. Suddenly, 50 Cent, Snoop Dogg, Mary J. Blige and a host of other performers took the field. A glance at the menu revealed a surprising throwback drink: an espresso martini. From a neighbouring table, a conversation drifted over, bemoaning the quality of the new Sex and the City show. It was official: we were back in the 2000s.

Nostalgia is just like it used to be!

As we haltingly lurch towards postcovidity, it is understandable that, in our shared social spaces, we’re looking back to even the recent past with fond nostalgia. In Toronto’s clubs in March, this phenomenon is also taking place. On March 27, 28 and 29, for example, the American band Rudder takes the stage at The Rex. For those of us who were in music school in the late 2000s, Rudder – whose eponymous debut album was released in 2007 – will likely be a familiar name. For those of you who didn’t waste your youth learning how to play lacklustre eighth-note lines over I’ve Got Rhythm – at least not in that decade – Rudder is an instrumental four-piece, comprising saxophonist Chris Cheek, keyboardist Henry Hey, bassist Tim Lefebvre, and drummer Keith Carlock. Musically, Rudder is something of a jazz musician’s take on a jam band, with priority given to original compositions over standards, backbeat over swing, and group dynamics over individual instrumental athleticism.

To fully understand the place of groups like Rudder in the psyche of music students of a particular age, a bit of musicological context seems necessary. Since funk’s emergence in the 1960s and 70s, there has always been crossover between funk and jazz. (Even the basic premise of these two musical styles as discrete genres is somewhat reductive, but for our purposes, we’ll maintain the distinction.) The fusion of jazz and funk begins in the late 1960s and early 1970s: albums such as Miles Davis’ In a Silent Way (1969), Bitches Brew (1970), On the Corner (1972), and Herbie Hancock’s Head Hunters (1973), stand out as foundational recordings of the genre.

The canonization of swing

From the beginning, however, there was also a sense that with funk the chamber-music ethos of bebop-based jazz had been abandoned in favour of blatant commercialism. While the popularity of fusion only grew throughout the 1970s and 80s, coincidentally or not, this period also marked the beginning of the proliferation of jazz studies programs in post-secondary institutions. As jazz education became formalized, canonization followed. At the centre of canonization is a simple question with a complex answer: what is jazz? To this day, the core skills that most jazz programs teach tend to be derived from bebop, and roughly adhere to the period of 1945 to 1965. Swing is prioritized over backbeat, the melodic minor scale is prioritized over the pentatonic minor and standards are prioritized over vamp-based originals.

“What I object to is the abandonment of the swing rhythm that is essential to jazz,” opines Wynton Marsalis, a musician whose principal position at Jazz at Lincoln Center has conferred on him the mantle of pedagogical authority. “There is no way that anyone can be a great jazz musician playing along to funk or rock rhythms. It just ain’t gonna happen.” Marsalis, certainly, has the credentials to stand behind his claims, but, for many musicians in jazz programs – certainly for those who were born well after the mainstream breakthrough of rock, funk and hip-hop – fusion often represents an honest concatenation of their genuine musical interests. While the sounds of Charlie Parker, John Coltrane and Miles Davis transcriptions abound from individual jazz program practice rooms, it is often, trust me, the sounds of fusion that can be heard through the doors to group rehearsal rooms, especially late at night.

In the mid-to-late 2000s, this music was John Scofield’s A Go Go; Joshua Redman’s Elastic and Momentum; the Brecker Brothers’ Heavy Metal Be-Bop; D’Angelo’s Voodoo; Robert Glasper’s In My Element; and countless others.

In Toronto, it was also Rudder. Their song SK8, from their debut album, was one of the first songs shared with me by a classmate in a listening session in 2007, during my first year in the University of Toronto’s jazz program; it was the kind of exploratory, improvisatory, groove-based music that spoke equally to my interests in swing and backbeat-based music. I don’t think that I made it to their December show at The Rex that year. But – now that the border is open, bands are touring and the prospect of spending an evening in an enclosed space with a roomful of other people is no longer the bone-chilling prospect that it so recently was – I’ll be at one of their shows this year.

And for the Rudderless

There is, of course, a lot of other excellent music happening in Toronto in March, both at The Rex and elsewhere. At Jazz Bistro, Montreal-based alto saxophonist Remi Bolduc appears on March 17 and 18, with Kirk MacDonald on tenor, Brian Dickinson on piano, Neil Swainson on bass and Terry Clarke on drums. Bolduc is one of Canada’s preeminent authorities on bebop-saxophone playing. (A faculty member at McGill, he is also a sought-after educator, and a voracious transcriber; his YouTube page contains approximately 400 transcriptions of Charlie Parker solos, as well as more modern saxophonists such as Jerry Bergonzi, Chris Potter and Rudresh Mahanthappa, pianists such as Herbie Hancock, and his own live performances.

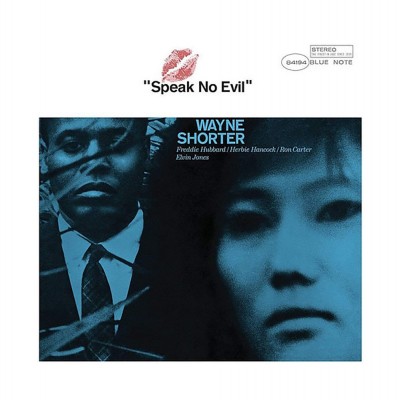

On March 31, Speak No Evil takes the stage, with Virginia MacDonald on clarinet, Mike Murley on tenor sax, Bernie Senensky on piano, Morgan Childs on drums and Swainson returning on bass. Speak No Evil, of course, is the classic Wayne Shorter album, released in 1964, with late-bop classics like Witch Hunt, Fee-Fi-Fo-Fum, and the famous title track.

On March 31, Speak No Evil takes the stage, with Virginia MacDonald on clarinet, Mike Murley on tenor sax, Bernie Senensky on piano, Morgan Childs on drums and Swainson returning on bass. Speak No Evil, of course, is the classic Wayne Shorter album, released in 1964, with late-bop classics like Witch Hunt, Fee-Fi-Fo-Fum, and the famous title track.

Colin Story is a jazz guitarist, writer and teacher based in Toronto. He can be reached at www.colinstory.com on Instagram and on Twitter.

Colin Story is a jazz guitarist, writer and teacher based in Toronto. He can be reached at www.colinstory.com on Instagram and on Twitter.