Barthold Kuijken

I’m glad that Toronto’s early music scene has such a wide variety of talent. But every so often, someone shows up and makes even the best musicians in the city take notice. This month, Toronto has a rare opportunity to hear a soloist who’s spent decades becoming one of the living legends of early music. You may not have heard of the celebrated Belgian flutist Barthold Kuijken (pronounced CAUW-ken) but to hear him in concert is to appreciate an artist who has mastered some of the most ornate and technically demanding works of music in the classical canon.

I’m glad that Toronto’s early music scene has such a wide variety of talent. But every so often, someone shows up and makes even the best musicians in the city take notice. This month, Toronto has a rare opportunity to hear a soloist who’s spent decades becoming one of the living legends of early music. You may not have heard of the celebrated Belgian flutist Barthold Kuijken (pronounced CAUW-ken) but to hear him in concert is to appreciate an artist who has mastered some of the most ornate and technically demanding works of music in the classical canon.

I’ll do my best to describe Kuijken’s influence on the early music movement without resorting to superlatives, but it won’t be easy. He belongs to what’s effectively the first generation of early music players (the previous generation being largely a bunch of eccentrics rather than professional musicians) who, finding modern classical performance practice unfulfilling, left promising careers as modern musicians to find a new style of performing. Given that there was no existing generation of musicians to teach them how to play differently, Kuijken et al. were complete autodidacts with only a handful of musical artifacts and historical treatises to guide them. Since then, Kuijken has become an educated performer and amassed an enviable instrument collection and library of historical sources. But what makes him unique is that, unlike other musicians of his generation, he didn’t have to do it alone. His older brother Weiland is one of the movement’s great viola da gambists, and another older brother, Sigiswald, not only became one the great violinists of the movement, but also founded La Petite Bande, one of the great European early music orchestras, in 1972.

Having family on his side helped Barthold Kuijken. Since moving to early music, he has performed extensively with Sigiswald’s orchestra as their principal flutist, played chamber music with both his brothers, and not incidentally also enjoyed a stellar career as one of the genre’s eminent soloists, generating a staggering discography along the way. This month, Baroque Music beside the Grange brings this legendary flutist to Heliconian Hall in Yorkville for a program that should serve to demonstrate Kuijken’s reputation as one of the greats. J.S. Bach’s sonata for unaccompanied flute, a piece by C.P.E Bach written for Frederick the Great, a couple of Telemann fantasias, and a suite by French composer Michel de la Barre are all pieces that were written for flutists to show off both artistic mastery and technical prowess, and I’m willing to bet that Kuijken doesn’t even find these tunes a fair match for his skills. If there’s one concert to make this month, this is it. Catch it on Sunday February 12 at 2:30 pm.

Profeti della Quinta: One generation inspires the next, and while the first generation of early music players tended to have the same musical and cultural background (Western European, conservatory trained, institutional misfits) the movement they founded means that younger players of today now come from all over the globe and have an entirely different view of the classical canon. A case in point is the Israeli vocal and instrumental group Profeti della Quinta, who came together as an early music group in Galilee and re-formed in Switzerland at the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis. Since then, the group has specialized in late-Renaissance Italian music, particularly in the music of Salomone Rossi, the 17th-century Italian-Jewish composer of madrigals, sacred vocal music and chamber music.

To hear Profeti della Quinta’s singing is to know that Rossi has been unfairly neglected by history. He’s a top-tier composer in the seconda prattica vein – meaning he could compose sacred polyphony in the style of Palestrina as well as use later techniques such as word-painting in more secular works – who was just as comfortable setting texts in Hebrew as in Italian. The effect on a modern audience is splendid as well as jarring, as if Monteverdi had decided one day that Hebrew was a better language than Italian for his madrigals, but the Profeti are both technically and interpretively flawless players who do justice to both this composer and this style of music. You can catch them in performance in Kingston at the Isabel Bader Centre for the Performing Arts on February 15 for an all-Rossi concert. If you can’t make it out to Kingston, the group has posted a number of music videos on their website quintaprofeti.com featuring the music of Rossi, Orlando di Lasso and Carlo Gesualdo, all of which I highly recommend.

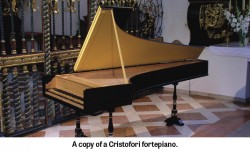

Ben Stein’s lute: Some artists choose to master the entire canon and others choose to specialize. Still others need no composer at all. We’ve known for years that performers in the Western art-music tradition were able to improvise. Bach’s Musical Offering, which was initially a challenge the composer received from Frederick the Great to improvise a three- and then six-part chromatic fugue, is a famous example, but many other famous composers were also great improvisers, and the tradition of improvisation stretches back much further than Bach. In the Renaissance and early Baroque, a young musician’s education included learning to improvise a melody over a commonly recognized bass line or series of chord changes – like the jazz standards of our time, but shorter and harmonically simpler. But knowing that improvisation was everywhere can change our view of compositions from the period. Printed music written down by gifted improvisers seems less like a painstakingly worked-out masterpiece and more like a surviving specimen from a larger group of improvisations, so players are supposed to perform music as if it were improvised. Less precise printings of music present other problems. But if they are just the shell of the music, rather than the final finished product, does that mean the performer is supposed to fill the gaps by ornamenting a bare melody or the chord progressions? Jazz musicians learn to improvise this way, but conservatory-trained classical players don’t. And as long as historically informed players can’t improvise in the style of the composer, it makes their supposed goal of re-creating the music as the composer heard it impossible.

Toronto-based lutenist Ben Stein may have an answer to this musical quandary. For the last several years, Stein has been researching how musicians of previous eras were taught musical improvisation, with a special focus on the conservatories of 18th-century Venice. Study and practice have let him re-create the part of a musical education from that period and, as a result, Stein can now improvise over a given melody or series of chord changes in much the same way that a 17th- or 18th-century musician would. If this sounds far-fetched to you, Stein can prove it – he’s going to both show and tell his musical discoveries in concert at a lecture-recital at Metropolitan United Church on February 10 at 7:30 pm. He’ll be joined by Lucas Harris on lute as well as Rezan Onen-Lapointe on violin and myself on harpsichord, and I’m pleased to say that Stein’s ability to teach classical musicians some necessary improv skills is as informative and entertaining for concert audiences as it is for his fellow musicians.

David Podgorski is a Toronto-based harpsichordist, music teacher and a founding member of Rezonance. He can be contacted at earlymusic@thewholenote.com.