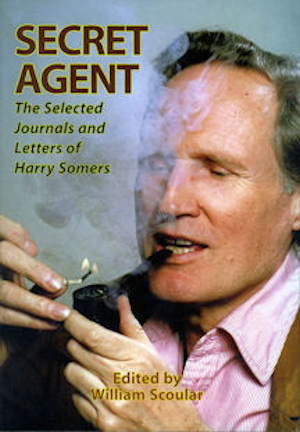

edited by William Scoular

352 pages, photos; $30.00

available from the Canadian Music Centre

Three weeks before Harry Somers died, he wrote in his journal, "I list my occupation as secret agent. Whenever I've been caught & it's been frequently, I confess to anything & everything. ‘Yes, yes,' I confess, escaping all torture. ‘You are a traditional conservative composer?' ‘YES.' ‘You are an eclectic?' ‘Oh YES.' ‘You have been at times an avant garde composer?' ‘I'll sign the paper!' ‘You're old hat?!' ‘Yes. Yes. A beat up old hat.'"

No-one except Somers himself could have come up with this. That's what makes these journals and letters so remarkable. Somers always stood out for his elegance, wit, charm, forthrightness and passionate dedication. We now have a whole new dimension on him - his thoughts, his feelings, his worries, and even what he read and listened to.

Somers' wife Barbara Chilcott and the editor William Scoular have done a Herculean job of assembling and editing the diaries and letters, written on scraps of paper over a period of 30 years. Their importance makes it all the more desirable that the next step be taken to have them fully annotated and indexed.

Certain situations need explaining, such as what happened in 1965 that would provoke Somers to curse ‘the commonwealth', ‘the Queen', ‘Ozawa', ‘Walter Hamburger' (sic), ‘Bright's champagne', ‘the government' and ‘Irving Glick', all in one breath? Important figures like E. Robert Schmitz need to be identified. Names like ‘gord rainor', ‘Milhoud', and ‘Crumm', misspelled by Somers - whether inadvertently or on purpose - should have their proper spelling noted. What annotations there are, given in square brackets in the text, are not always accurate. The published journal reads, "I remember Krenek [president of the USSR's composers' union] referring to Copland as superficial." But here Somers is surely referring to the Austrian composer Ernst Krenek, not the Soviet composer Tikhon Khrennikov, who was Somers' dinner companion when he visited the USSR in 1976.

Somers' speculations about writing an autobiography come up constantly in these pages. "There are many sides of many things I've not spoken of," he wrote in 1995. Fortunately he left this candid, fascinating journal, and along with his letters, it makes an essential contribution to the cultural life of this country. A terrific collection of photos and a DVD containing clips of TV and documentary interviews give readers a sense of his physical presence.

The People's Artist: Prokofiev's Soviet Years

The People's Artist: Prokofiev's Soviet Years

by Simon Morrison

Oxford University Press

504 pages, photos; $32.95

If the secret agent who figures in Harry Somers' journal was a romanticized fantasy, the secret agents in Prokofiev's life were real, nasty, and dangerous - from the Russian émigré cellist in Hollywood who made sure Prokofiev returned to the Soviet Union, to the malicious head of the Union of Soviet Composers, Tikhon Khrennikov, who Somers had found to be "terribly kind" when he met him in Moscow.

This brilliant chronicle of Prokofiev's final years focuses on why he returned to what was now the Soviet Union, and how that irrevocable move affected his life and music. "He thought to influence Soviet cultural policy," writes Morrison, "but instead it influenced him."

Morrison explores how Prokofiev's ambition, vanity, and naiveté led him to his fateful decision. It's clear from his diaries (now being published in English) that he missed his homeland. But he was lured by offers of performances and money. Morrison considers the influence of his fervent Christian Science spiritualism, which likely prevented him from seeing the repression, incarcerations and murders of artists that were occurring regularly in the Soviet Union under Stalin.Yet he shows that Prokofiev in fact had some sense of the personal and artistic freedom he would be sacrificing. In any case, as soon as he had moved his wife Lina and their two sons from Paris to Moscow, he could only travel abroad with Lina if he left his two sons behind. By 1938, neither he nor Lina was allowed to leave at all.

But as difficult as things gradually became for Prokofiev, they were far worse for Lina, who was not even Russian. First, Prokofiev left her for a young admirer, and then, when she tried to leave the USSR, she ended up spending years in Soviet camps on fabricated charges of treason.

Morrison is a Canadian scholar now teaching at Princeton. He has made full use of his unprecedented access to unpublished documents and scores now in the Russian State Archives. Morrison's meticulous endnotes and index makes this detailed biography accessible, and his elegant writing style makes it thoroughly engrossing to read.

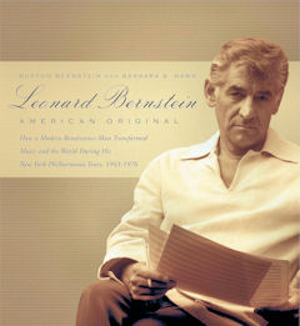

edited by Burton Bernstein and Barbara B. Haws

HarperCollins

240 pages, photos; $31.95

For years, Leonard Bernstein's father Sam pressured his musically precocious eldest son to go into the family beauty-supplies business. Later he defended himself by saying, "How could I know he would grow up to be a Leonard Bernstein?" As his father had finally figured out, Leonard Bernstein was an original. But no-one could live up to the title of this book and be a "modern renaissance man" who "transformed music and the world" - not even this charismatic conductor, composer, writer and educator. Fortunately the ten essays in this book are less starry-eyed and more incisive than the title would suggest. Together, they offer a well-balanced portrait of a complex figure.

There's an eloquent memoir by music critic Alan Rich, who admits to often being hard on Bernstein, mostly for ignoring contemporary music. Historian Paul Boyer discusses how Bernstein added a political dimension to his role as conductor of the New York Philharmonic. Like Prokofiev, he believed that art not only reflects but influences social reality. His outspoken support for issues such as civil liberties, environmental protection and world peace was considered so audacious at the time that he ended up with an FBI file almost 700 pages long.

Unlike the Soviet composer, he did achieve some influence. But, as his younger brother Burton Bernstein writes in one of his memorable chapter-by-chapter commentaries, he paid a price - in the press at least - for what his brother considers his naiveté. American composer John Adams offers the perspective of a young man first discovering Bernstein. "I thought I'd found the model for what the future of classical music in America would be," he writes.

The splendid photos and documents enrich the texts. My favorite photo, from 1970, shows Bernstein in leisure clothes coaching his baseball team, the Philharmonic Penguins. Beside him, watching intently in his baseball uniform and cap, is his protégé Seiji Ozawa, who would have just finished his stint as conductor of the Toronto Symphony.

The Toronto Symphony performs two works by Bernstein, Three Dance Episodes from On the Town, and Symphonic Dances from West Side Story, on May 13 at 8:00 and May 14 at 2:00.

Bernstein's West Side Story is on stage at the Stratford Festival from June 5 until October 31.