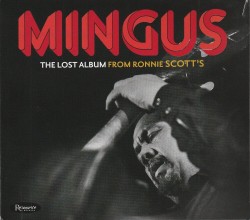

Mingus – The Lost Album from Ronnie Scott’s

Mingus – The Lost Album from Ronnie Scott’s

Charles Mingus Sextet

Resonance Records HCD-2063 (resonancerecords.org)

Between 1956 and 1965, composer and bassist Charles Mingus stretched the range of jazz composition with the tumult and keening lyricism of LPs like Pithecanthropus Erectus, Mingus Ah Um and The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady, simultaneously putting the civil rights movement on the jazz-club stage. This three-CD set presents him a few years later, leading his sextet on the last two nights of a two-week run at Ronnie Scott’s eponymous London club in 1972. Originally intended for release on Columbia, that possibility died with the label’s 1973 purge of acoustic jazz greats: Mingus, Bill Evans, Keith Jarrett and Ornette Coleman.

1972 wasn’t Mingus’ happiest hour. He had been concentrating on extended compositions, including a string quartet and the massive orchestral work that would become Epitaph, during an era dominated by the knotty creativity of free jazz and the commercial juggernaut of fusion; however, the band here still pulses with life when reworking Mingus’ earlier masterworks, stretching them to a half-hour and beyond: the dense, yearning harmonies of Orange Was the Color of Her Dress, Then Blue Silk, extends Duke Ellington’s influence into a new expressionism; Fables of Faubus adds fresh dissonances while remaining a seething yet comic refutation of segregation. Two new works have similar dimension: Mind-Readers’ Convention in Milano (AKA Number 29) is kaleidoscopic, while The Man Who Never Sleeps is imbued with a lustrous lyricism by trumpeter Jon Faddis, then a brilliant teenager. Alto saxophonist Charles McPherson is consistently good, improvising fleet and fluid lines across Mingus’ insistent shifting rhythms. Bobby Jones, another regular, was a journeyman saxophonist who could stretch toward greatness on those turbulent undercurrents.

For all of Mingus’ raging assaults on the bar culture of jazz (he once began a studio recording, Charles Mingus Presents Charles Mingus, by admonishing imaginary waitstaff and customers to cease glass clinking, cash register clanging, etc.), he was (even in that double-edged comedy) an entertaining jazz musician (he began his career as sideman to Ellington and Louis Armstrong), but one who had brought uncomfortable truths to the stage. Some of the humour here is satiric, like the bass solo that concludes Fables of Faubus by collaging minstrel songs and anthems, including Turkey in the Straw, Dixie, My Old Kentucky Home and the Star-Spangled Banner, but there’s also low musical humour. Pianist John Foster, otherwise unmemorable, contributes cliched blues vocals and an imitation of Louis Armstrong on Pops. Roy Brooks, the drummer, plays an extended solo on musical saw. One leaves with an uneasy sense that in his later years, Mingus’ art, designed to make audiences uncomfortable, might backfire, making the audience comfortable and Mingus the opposite. In history’s hall of mirrors, that might again make a contemporary audience uncomfortable.