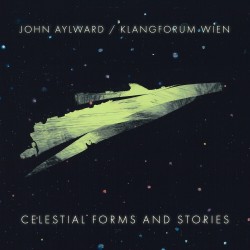

John Aylward – Celestial Forms and Stories - Members of Klangforum Wien

John Aylward – Celestial Forms and Stories

John Aylward – Celestial Forms and Stories

Members of Klangforum Wien

New Focus Recordings FCR320 (newfocusrecordings.com)

The composer John Aylward seems committed to the idea of pushing the language of music into unchartered territory. His work consistently suggests that only the relatively extreme is interesting. In all of the radicalism that this soundscape suggests, Aylward also manages to remain true to bright sonorous textures evoked in vivid phrases that leap and gambol with elliptical geometry. Yet every so often the percussive impact of his work transforms its flowing character into a kaleidoscopic melee of scurrying voices which are built up layer upon layer.

His suite Celestial Forms and Stories reimagines characters and narratives from Ovid’s classic, Metamorphosis. The five pieces have been arranged in the form of an atmospheric suite inspired as much by the Latin epic poem as it is by the dissertation, Ovid and Universal Contiguity, by Italo Calvino, itself an iconic treatise, epic in breadth and scope.

Celestial Forms and Stories begins with Daedalus and the darkly dramatic voyage of Icarus, its lofty melodic line ascending rhythmically into the heat of the rarefied realm. The transcendent motion of Mercury exquisitely evokes the winged messenger colliding with the obdurate Battus. The suite melts into the buzzing, swooning mayfly, Ephemera. Narcissus follows, trapped in the glassy tomb with Echo. The suite climaxes in the restless drama of Ananke with its forceful, tumbling rhythmic changes. The remarkable musicians of Klangforum Wien perform this work with vivid orchestral colours and preeminent virtuosity.