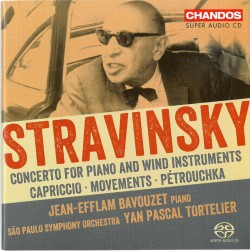

Stravinsky – Concerto for Piano and Winds; Capriccio; Movements; Petrouchka

Stravinsky – Concerto for Piano and Winds; Capriccio; Movements; Petrouchka

Stravinsky – Concerto for Piano and Winds; Capriccio; Movements; Petrouchka

Jean-Efflam Bavouzet; São Paulo Symphony Orchestra; Yan Pascal Tortelier

Chandos CHSA 5147

In addition to his frequent appearances as a conductor of his own music, the illustrious genius known as Igor Stravinsky composed a number of concertos for his exclusive use as a pianist, ready alternatives to the all-too-familiar requests for yet another performance of the Firebird Suite. A stunning new Stravinsky recording by the esteemed pianist Jean-Efflam Bavouzet brings together these concertos and then some.

Stravinsky’s 1924 Concerto for piano and wind instruments opens this excellent disc, followed by the Capriccio for piano and orchestra from 1929. Both works are delightful concoctions from the composer’s carefree French epoch, teeming with bonhomie and sparkling wit and recorded in flatteringly crystalline sound. Movements for piano and orchestra (1959) is late Stravinsky and represents the culmination of a growing interest in the serial techniques advocated by his arch-nemesis Arnold Schoenberg after the latter’s death in 1951. This is an intentionally esoteric work that may puzzle some listeners though connoisseurs will recognize here a very fine and scrupulous reading. The disc concludes with a fiery performance of the 1947 version of the ballet score Pétrouchka, a work that was originally conceived as a piano concerto. An audibly grunting Yan Pascal Tortelier elicits an electric response from the excellent São Paulo musicians while Bavouzet delights in playing the prominent piano part from inside the orchestra. The recording of this densely orchestrated work suffers at times from congested orchestral balances (notably so in The Shrove Tide Fair section) that pale in comparison with Stravinsky’s own 1960 recording, brilliantly mixed by the late John McClure and still my personal favourite.