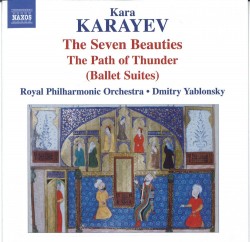

Kara Karayev – The Seven Beauties; The Path of Thunder

Kara Karayev – The Seven Beauties; The Path of Thunder

Kara Karayev – The Seven Beauties; The Path of Thunder

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra; Dmitry Yablonsky

Naxos 8.573122

For listeners unfamiliar with Azerbaijani composer Kara Karayev (1918-1982), these ballet suites are an attractive introduction. Karayev studied with Shostakovich, and his rhythmic, tuneful music is well-suited to the ballet. The two works’ stories lend themselves to Karayev’s incorporation, respectively, of Azerbaijani folk song and dance, and of African and African-American musical traditions.

Karayev remained acceptable in the Soviet musical establishment at a time when the government criticized other composers severely for “formalism.” The story and folk elements in The Seven Beauties(1949) no doubt helped, as did his conventional and conservative musical style. His melodic gift is notable, as in the “Adagio”’s horn solo, and he sets the mood in each of The Seven Portraits with a few deft, colourful strokes. The solo winds of the Royal Philharmonic excel here. Yablonsky paces the orchestra well, leading to a climax just before the final Procession.

The Path of Thunder (1958) dates from the Khrushchev years, with a tragic story from South Africa involving lovers of different races. The music is now more hard-edged and spiky, with influences of Stravinsky and of Ravel`s Bolero. Syncopations and irregular metres are effective, as in the “Finale”’s 7/4 ostinato. The “Scene and Duet” of the lovers is particularly attractive, with violin and cello solos that are played beautifully by Royal Philharmonic principals. The passionate and idiomatic performances on this disc led by Dmitry Yablonsky make it a significant addition to the recorded repertoire.