Interpreting Roscoe Mitchell’s Challenging and Influential Music

Confirming once again the continued vitality of the first generation of Free Music avatars, at 76, saxophonist Roscoe Mitchell is still innovating with divergent aspects of instrumentation and arrangements. One demonstration of this will occur Sunday, October 16, when he leads a mixed, 15-member, Montreal-Toronto ensemble through several of his compositions as part of the Music Gallery’s annual X-Avant Festival. Other components of note include concerts by the likes of composer Pauline Oliveros and violinist Sarah Neufeld, but Mitchell, co-founder of the Art Ensemble of Chicago (AEC), and a stalwart of Chicago’s Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), has a long relationship with Toronto going back to the early 1970s when he recorded some groundbreaking LPs in the city.

An instance of Mitchell’s skill as a composer and performer in a miniature yet multi-instrumental context is Angel City (RogueArt ROG-0061 rogueart.com). Developing a single, 55-minute variant of his composition, Mitchell plays sopranino and bass saxophones, bass recorder, baroque flute, whistles and percussion. His associates are James Fei on sopranino, alto and baritone saxophones, bass and contrabass clarinets and analog electronics, plus William Winant expressing himself via marimba, timpani, bass drum, snare, cymbals, gongs, wood blocks, percussion and three types of bells: orchestral, tubular and cow [!]. Literally beginning with bells and whistles, Angel City advances logically with alternating sequences of solo and group work, gentle and harsh timbres, light and dark shadings, plus a judicious balance between sound and silence(s). With so many instruments, the three devise notable motifs that balance contrapuntal high-and-low-pitched reed elaborations as Winant clips, clanks, clinks and crashes through percussion development, deviating to textures from a disassociated reed shrill and singular marimba-like plonk as solitary as a prairie landscape. Another interlude encompasses bell jingling that backs droning growls from matching bass and baritone saxophone. Sophisticated in utilizing little (percussion) instruments, plus using compositional ploys, Mitchell interpolates false climaxes throughout Angel City, marking them with protracted pauses as carefully as if on score paper. Unexpectedly, counter themes arise and are repeated, with a couple roaring like cannons from the 1812 Overture, with others propelled by recorder sequences so courtly they’re almost florid. From menacing kettle-drum foreshadowing to delicate-as-microsurgery mallet work on triangles, Winant confirms his knack as a sound colourist while maintaining percussion continuum. Fei is equally supportive. But since he and Mitchell share work on reeds of similar timbres, it’s difficult to assign individual kudos. Many times one pushes the theme forward while the other cunningly decorates and amplifies the initial line. Eventually Mitchell’s bass sax burping out a swinging but sophisticated line joins with Winant’s polyrhythmic cacophony that appears to vibrate every struck instrument at once to create a multiphonic finale which slurs away into silence.

An instance of Mitchell’s skill as a composer and performer in a miniature yet multi-instrumental context is Angel City (RogueArt ROG-0061 rogueart.com). Developing a single, 55-minute variant of his composition, Mitchell plays sopranino and bass saxophones, bass recorder, baroque flute, whistles and percussion. His associates are James Fei on sopranino, alto and baritone saxophones, bass and contrabass clarinets and analog electronics, plus William Winant expressing himself via marimba, timpani, bass drum, snare, cymbals, gongs, wood blocks, percussion and three types of bells: orchestral, tubular and cow [!]. Literally beginning with bells and whistles, Angel City advances logically with alternating sequences of solo and group work, gentle and harsh timbres, light and dark shadings, plus a judicious balance between sound and silence(s). With so many instruments, the three devise notable motifs that balance contrapuntal high-and-low-pitched reed elaborations as Winant clips, clanks, clinks and crashes through percussion development, deviating to textures from a disassociated reed shrill and singular marimba-like plonk as solitary as a prairie landscape. Another interlude encompasses bell jingling that backs droning growls from matching bass and baritone saxophone. Sophisticated in utilizing little (percussion) instruments, plus using compositional ploys, Mitchell interpolates false climaxes throughout Angel City, marking them with protracted pauses as carefully as if on score paper. Unexpectedly, counter themes arise and are repeated, with a couple roaring like cannons from the 1812 Overture, with others propelled by recorder sequences so courtly they’re almost florid. From menacing kettle-drum foreshadowing to delicate-as-microsurgery mallet work on triangles, Winant confirms his knack as a sound colourist while maintaining percussion continuum. Fei is equally supportive. But since he and Mitchell share work on reeds of similar timbres, it’s difficult to assign individual kudos. Many times one pushes the theme forward while the other cunningly decorates and amplifies the initial line. Eventually Mitchell’s bass sax burping out a swinging but sophisticated line joins with Winant’s polyrhythmic cacophony that appears to vibrate every struck instrument at once to create a multiphonic finale which slurs away into silence.

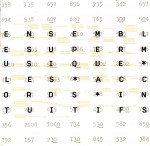

About half the musicians interpreting Mitchell’s Music Gallery compositions reside in Montreal. Ensemble SuperMusique’s Les accords intuitifs (Ambiances Magnétiques AM 222 actuellecd.com) features a large group of improvisers playing compositions by alto saxophonist/vocalist Joane Hétu and guitarist Bernard Falaise, as well as contemporary pieces by violinist Malcolm Goldstein and two mid-1970s scores by Montrealers Yves Bouliane and Raymond Gervais. All tracks are moored in the territory where group concert music conventions, free-form soloing and rock-music tempi collide. Like researchers experimenting with space medicine discovering unexpected futuristic tropes, new currents arise when Martin Tétrault’s turntables, Vergil Sharkya’s synthesizer and Alexandre St-Onge or Nicolas Caloia’s electric basses are given leeway. Although the stop-time climaxes, cycling marches and the semi-serious vocalizing on Hétu’s Pour ne pas désespérer seul appear related more to Frank Zappa than Iannis Xenakis, Mitchell would recognize asides created by percussive AEC-pioneered little instruments, as well as sharpened saxophone cries that play off against Scott Thomson’s plunger trombone and Craig Pedersen’s soaring trumpet. Unsurprisingly, although Goldstein’s Jeux de cartes expands and contracts with tremolo flutters prodded by Danielle P. Roger and Isaiah Ceccarelli’s percussion, most of the crackling excitement is engendered by Joshua Zubot’s violin glissandi. Another standout performance is Gervais’ title track. Uncommonly contemporary, the piece mixes overhanging crescendos growled by the entire ensemble with spidery contrasts between the solo strategies of St-Onge and acoustic bassist Aaron Lumley. The ending is left unresolved as cymbal-clanking finality is subverted by synthesizer squeaks and guitar string pops.

About half the musicians interpreting Mitchell’s Music Gallery compositions reside in Montreal. Ensemble SuperMusique’s Les accords intuitifs (Ambiances Magnétiques AM 222 actuellecd.com) features a large group of improvisers playing compositions by alto saxophonist/vocalist Joane Hétu and guitarist Bernard Falaise, as well as contemporary pieces by violinist Malcolm Goldstein and two mid-1970s scores by Montrealers Yves Bouliane and Raymond Gervais. All tracks are moored in the territory where group concert music conventions, free-form soloing and rock-music tempi collide. Like researchers experimenting with space medicine discovering unexpected futuristic tropes, new currents arise when Martin Tétrault’s turntables, Vergil Sharkya’s synthesizer and Alexandre St-Onge or Nicolas Caloia’s electric basses are given leeway. Although the stop-time climaxes, cycling marches and the semi-serious vocalizing on Hétu’s Pour ne pas désespérer seul appear related more to Frank Zappa than Iannis Xenakis, Mitchell would recognize asides created by percussive AEC-pioneered little instruments, as well as sharpened saxophone cries that play off against Scott Thomson’s plunger trombone and Craig Pedersen’s soaring trumpet. Unsurprisingly, although Goldstein’s Jeux de cartes expands and contracts with tremolo flutters prodded by Danielle P. Roger and Isaiah Ceccarelli’s percussion, most of the crackling excitement is engendered by Joshua Zubot’s violin glissandi. Another standout performance is Gervais’ title track. Uncommonly contemporary, the piece mixes overhanging crescendos growled by the entire ensemble with spidery contrasts between the solo strategies of St-Onge and acoustic bassist Aaron Lumley. The ending is left unresolved as cymbal-clanking finality is subverted by synthesizer squeaks and guitar string pops.

British soprano and tenor saxophonist John Butcher would likely name as his antecedents European stylists like Evan Parker and contemporary notated and minimalist music. But when paired with the Portuguese Red Trio – pianist Rodrigo Pinheiro, bassist Hernani Faustino and drummer Gabriel Ferrandini – on Summer Skyshift (Clean Feed CF 372 CD cleanfeedrecords.com), the performance suggests a fantasy film in which mild-mannered types are transformed into superheroes. Syncopating at jet engine speeds with irregular vibration emanating from both of Butcher’s horns, congruent zealous string stretching and screeched percussion advance the parallels to the AEC or similar Mitchell ensembles. Playing with devastating power as he double and triple tongues, Butcher appears to be vacuuming up every tone from the atmosphere, then ejecting the outcome in a variety of shadings and pitches. With his timbres on the lower-pitched horn cramped and dissonant as a freeway at rush hour, he’s equally fierce on soprano, puffing and gargling timbres that twirl and twist as Pinheiro’s speedy playing creates resonating accompaniment. Faustino adds to the high-pressure narrative, contrasting his chunky string strums with Butcher’s tongue slaps that could levitate a bowling ball. Craggy and barbed, the extended final track is more adroitly cadenced. Ferrandini’s percussive smacks and sprawls plus equivalent intensity from the others’ strings and keys push Butcher’s initial flatline tone to passionate timbre-spewing. Like an Olympic competitor reaching the finish line, the high-strung exposition relaxes into downward piano chords and a bowed bass turn.

British soprano and tenor saxophonist John Butcher would likely name as his antecedents European stylists like Evan Parker and contemporary notated and minimalist music. But when paired with the Portuguese Red Trio – pianist Rodrigo Pinheiro, bassist Hernani Faustino and drummer Gabriel Ferrandini – on Summer Skyshift (Clean Feed CF 372 CD cleanfeedrecords.com), the performance suggests a fantasy film in which mild-mannered types are transformed into superheroes. Syncopating at jet engine speeds with irregular vibration emanating from both of Butcher’s horns, congruent zealous string stretching and screeched percussion advance the parallels to the AEC or similar Mitchell ensembles. Playing with devastating power as he double and triple tongues, Butcher appears to be vacuuming up every tone from the atmosphere, then ejecting the outcome in a variety of shadings and pitches. With his timbres on the lower-pitched horn cramped and dissonant as a freeway at rush hour, he’s equally fierce on soprano, puffing and gargling timbres that twirl and twist as Pinheiro’s speedy playing creates resonating accompaniment. Faustino adds to the high-pressure narrative, contrasting his chunky string strums with Butcher’s tongue slaps that could levitate a bowling ball. Craggy and barbed, the extended final track is more adroitly cadenced. Ferrandini’s percussive smacks and sprawls plus equivalent intensity from the others’ strings and keys push Butcher’s initial flatline tone to passionate timbre-spewing. Like an Olympic competitor reaching the finish line, the high-strung exposition relaxes into downward piano chords and a bowed bass turn.

Western European musicians aren’t the only ones influenced by sound conceptions. Many of the tropes used regularly on Intuitus (NoBusiness NBLP 93 nobusinessrecords.com) had their origins in Mitchell’s extended sound experiments. As an indication of that reach, the players on this Vilnius-recorded set are two Lithuanians, Liudas Mockūnas, who plays soprano and tenor saxophones, clarinet and bass clarinet and bassist Eugenijus Kanevičius, plus Russian percussionist Vladimir Tarasov. Tarasov applies textures available from cimbalom, bells, xylophone and hunting horn to break up and personalize the rhythmic thrust here. Using an upright bass with electronic extensions, Kanevičius’ texture is not only reliable, but also adaptable enough to add plectrum-instrument-like colouration to the ten selections. A track such as Time Loop Backwards, for instance, bristles with tones propelled by the bassist’s Charles Mingus-like bulkiness as Tarasov’s hand drumming curdles like cheese churned from curds and whey into polyrhythmic bass drum whacks inset with cymbal clacks. Exhibiting a Jekyll and Hyde duality, Mockūnas moves from narrow clarinet puffs to outsized split tones and peevish snarls. Following an introductory grounded bass solo on Once around the Corner, the reedist demonstrates his mainstream-oriented tenor saxophone facility, propelling the theme with relaxed forward motion. True to AACM precepts, though, the comfortable narration is shaken up with circular-breathed clarinet puffs and an archer-like propelling of arco tones from Kanevičius as the pitch rises before the conclusion. Capable of nasal asides or slide-whistle-like peeping elsewhere, with equivalent responses from the other two, the saxophonist’s authoritative tenor tone defines the concluding Searching for Peace. As the bassist’s tremolo strategy solidifies the exposition, the drummer tickles small percussion instruments. The heaving Baltic qualities of Mockūnas’ vibrations confirm that Mitchell’s American ideals adapt well to local musical use.

Western European musicians aren’t the only ones influenced by sound conceptions. Many of the tropes used regularly on Intuitus (NoBusiness NBLP 93 nobusinessrecords.com) had their origins in Mitchell’s extended sound experiments. As an indication of that reach, the players on this Vilnius-recorded set are two Lithuanians, Liudas Mockūnas, who plays soprano and tenor saxophones, clarinet and bass clarinet and bassist Eugenijus Kanevičius, plus Russian percussionist Vladimir Tarasov. Tarasov applies textures available from cimbalom, bells, xylophone and hunting horn to break up and personalize the rhythmic thrust here. Using an upright bass with electronic extensions, Kanevičius’ texture is not only reliable, but also adaptable enough to add plectrum-instrument-like colouration to the ten selections. A track such as Time Loop Backwards, for instance, bristles with tones propelled by the bassist’s Charles Mingus-like bulkiness as Tarasov’s hand drumming curdles like cheese churned from curds and whey into polyrhythmic bass drum whacks inset with cymbal clacks. Exhibiting a Jekyll and Hyde duality, Mockūnas moves from narrow clarinet puffs to outsized split tones and peevish snarls. Following an introductory grounded bass solo on Once around the Corner, the reedist demonstrates his mainstream-oriented tenor saxophone facility, propelling the theme with relaxed forward motion. True to AACM precepts, though, the comfortable narration is shaken up with circular-breathed clarinet puffs and an archer-like propelling of arco tones from Kanevičius as the pitch rises before the conclusion. Capable of nasal asides or slide-whistle-like peeping elsewhere, with equivalent responses from the other two, the saxophonist’s authoritative tenor tone defines the concluding Searching for Peace. As the bassist’s tremolo strategy solidifies the exposition, the drummer tickles small percussion instruments. The heaving Baltic qualities of Mockūnas’ vibrations confirm that Mitchell’s American ideals adapt well to local musical use.

Another AACM member who has matched Mitchell’s accomplishments as an instrumentalist, albeit in more conventional jazz, is drummer Jack DeJohnette. Best known for his decades-long collaboration with Keith Jarrett, DeJohnette, 74, is like a harlequin clothing himself in two-tone popular and progressive music-garments on his own discs. In Movement (ECM 2488 ecmrecords.com), for instance, finds him playing electronics and piano plus percussion, with his own improvisations mixed into a program of lines from Bill Evans, John Coltrane and Earth Wind & Fire (EWF). His associates here are sons of jazz legends: Coltrane’s son Ravi, 51, who plays soprano, sopranino and tenor saxophones, and the son of bassist Jimmy Garrison, Matthew, 46, whose instruments are electronics and electric bass. More conventional soloists than their respective fathers, Garrison has the facility to thump a beat as well as output sympathetic guitar-like strokes. As for Coltrane, he loses when measured against a musician whose stature in jazz is comparable to that of a combination of Beethoven and Frank Sinatra. Playing his father’s Alabama, Ravi’s sense of dynamics proves he’s more talented that Frank Sinatra Jr., but most of the drama comes via DeJohnette’s crystal clear drumming and Garrison’s flamenco-like strumming. EWF’s Serpentine Fire allows him to stretch his soprano into double tongued tone flutters, Garrison’s rhythm guitar-like strums and drum backbeat add some fire, but the result is more restrained fusion than outright funk. More notable are improvisations such as Two Jimmys and Rashied. The former reaches the soul inferences aimed for elsewhere, shoehorning some Orientalism via synthesizer licks as well. DeJohnette’s beat is again faultless and on tenor saxophone Ravi Coltrane smoothly outputs the theme honouring John Coltrane’s final drummer, the other piece opens up enough to let DeJohnette demonstrate that he could easily have filled that kit chair. With cupped cymbal splashes and rugged ruffs aimed at him, Coltrane is like a boxer challenged by a seasoned opponent, flying through the material with a bellicose combination of split tones and overblowing. Like an Olympian who competes in both swimming and track, DeJohnette demonstrates his versatility on Soulful Ballad, where he propels the mood from the piano with Romantic glissandi reminiscent of Evans and Jarrett.

Another AACM member who has matched Mitchell’s accomplishments as an instrumentalist, albeit in more conventional jazz, is drummer Jack DeJohnette. Best known for his decades-long collaboration with Keith Jarrett, DeJohnette, 74, is like a harlequin clothing himself in two-tone popular and progressive music-garments on his own discs. In Movement (ECM 2488 ecmrecords.com), for instance, finds him playing electronics and piano plus percussion, with his own improvisations mixed into a program of lines from Bill Evans, John Coltrane and Earth Wind & Fire (EWF). His associates here are sons of jazz legends: Coltrane’s son Ravi, 51, who plays soprano, sopranino and tenor saxophones, and the son of bassist Jimmy Garrison, Matthew, 46, whose instruments are electronics and electric bass. More conventional soloists than their respective fathers, Garrison has the facility to thump a beat as well as output sympathetic guitar-like strokes. As for Coltrane, he loses when measured against a musician whose stature in jazz is comparable to that of a combination of Beethoven and Frank Sinatra. Playing his father’s Alabama, Ravi’s sense of dynamics proves he’s more talented that Frank Sinatra Jr., but most of the drama comes via DeJohnette’s crystal clear drumming and Garrison’s flamenco-like strumming. EWF’s Serpentine Fire allows him to stretch his soprano into double tongued tone flutters, Garrison’s rhythm guitar-like strums and drum backbeat add some fire, but the result is more restrained fusion than outright funk. More notable are improvisations such as Two Jimmys and Rashied. The former reaches the soul inferences aimed for elsewhere, shoehorning some Orientalism via synthesizer licks as well. DeJohnette’s beat is again faultless and on tenor saxophone Ravi Coltrane smoothly outputs the theme honouring John Coltrane’s final drummer, the other piece opens up enough to let DeJohnette demonstrate that he could easily have filled that kit chair. With cupped cymbal splashes and rugged ruffs aimed at him, Coltrane is like a boxer challenged by a seasoned opponent, flying through the material with a bellicose combination of split tones and overblowing. Like an Olympian who competes in both swimming and track, DeJohnette demonstrates his versatility on Soulful Ballad, where he propels the mood from the piano with Romantic glissandi reminiscent of Evans and Jarrett.

Pacific

Pacific