As the parameters of jazz and improvised music continue to expand during the 21st century, so does the bedrock of theme material and instrumental extensions. While many improvisers still record classic discs that are completely free form, other creative musicians alter and bend exciting sounds to create original programs.

While interpretations of Thelonious Monk classics are nothing new, especially as his stature has grown among conventional and conservative players since his 1982 death, performances of these nine melodies on solo viola is almost certainly unique. But that’s exactly what Romanian-born George Dumitriu, who now teaches in Utrecht, has done with Monk on Viola (Evil Rabbit ERR 36 evilrabbitrecords.eu). While his playing encompasses microtones and repetition, and his instrument includes preparations, the dominant approach involves deftly reconstituting the pieces so that familiar themes are present along with original variations. This is aptly displayed on ‘Round Midnight, Monk’s best-known composition, which begins with woody slaps, and angled string sawing until a twanging variant of the melody is heard and recognized at the same time as it’s pinched and descends the scale. The concluding Crepuscule with Nellie gets a similar treatment, vibrating in and out of tempo as adagio rubs and spiccato slides change places, culminating in an exciting col legno finale. Analogous strategies are exhibited on the other seven tracks. Boo Boo’s Birthday almost becomes a simple country dance tune, then in a reversal deploys and fragments the theme with high-pitched, multi-string changes. Double stops finally become a jagged stroke representation of the melody. More traditionally Trinkle Tinkle begins and ends stating and recapping the head, with an initial high-pitched race up the scale sliding from presto to moderato and repeating melody variants as it descends. Fractured enough to be distinctive, this idiosyncratic program doesn’t subvert Monk’s purposeful body of works.

While interpretations of Thelonious Monk classics are nothing new, especially as his stature has grown among conventional and conservative players since his 1982 death, performances of these nine melodies on solo viola is almost certainly unique. But that’s exactly what Romanian-born George Dumitriu, who now teaches in Utrecht, has done with Monk on Viola (Evil Rabbit ERR 36 evilrabbitrecords.eu). While his playing encompasses microtones and repetition, and his instrument includes preparations, the dominant approach involves deftly reconstituting the pieces so that familiar themes are present along with original variations. This is aptly displayed on ‘Round Midnight, Monk’s best-known composition, which begins with woody slaps, and angled string sawing until a twanging variant of the melody is heard and recognized at the same time as it’s pinched and descends the scale. The concluding Crepuscule with Nellie gets a similar treatment, vibrating in and out of tempo as adagio rubs and spiccato slides change places, culminating in an exciting col legno finale. Analogous strategies are exhibited on the other seven tracks. Boo Boo’s Birthday almost becomes a simple country dance tune, then in a reversal deploys and fragments the theme with high-pitched, multi-string changes. Double stops finally become a jagged stroke representation of the melody. More traditionally Trinkle Tinkle begins and ends stating and recapping the head, with an initial high-pitched race up the scale sliding from presto to moderato and repeating melody variants as it descends. Fractured enough to be distinctive, this idiosyncratic program doesn’t subvert Monk’s purposeful body of works.

Akin to this strategy of reconstitution and homage occurs on Montrealer-turned-Manhattanite Rick Rosato’s solo bass recreation of a set of distinctive country blues songs plus a couple of jazz classics on his aptly named Homage CD (rickrosato/bandcamp.com/album/homage). Applying full intensity to this less-than-23 minute disc, he uses different tunings and mutes to attain the yearning resonation of the original tunes. Throughout his full rounded tone and supple fingering makes up for any lack of accompaniment. Serendipitously he too interprets Crepuscule with Nellie. Remaining mostly in the instrument’s bass clef, he plucks his way though bluesy variations before exposing the theme at the two-thirds mark. Ironically Elvin’s Guitar Blues, composed by powerhouse drummer Elvin Jones, is more highly rhythmic and in context sounds as traditional as the venerable tunes surrounding it. These range from Mississippi John Hurt’s songster classic Boys, You’re Welcome played with a spry guitar-like lilt, to Muddy Waters’ I Can’t Be Satisfied, the epitome of hard blues and harbinger of R&B. On the latter Rosato emphasizes the beat with double and triple strokes and pumped-up theme variations before shaking his way to full theme statement. Overall, he signals his homage and adaptation best on Skip James’ Hard Time Killing Floor Blues. He hammers strings to bend notes and repeats choruses so that the original’s emotional pressure and his distinctive woody vibrations are given equal play.

Akin to this strategy of reconstitution and homage occurs on Montrealer-turned-Manhattanite Rick Rosato’s solo bass recreation of a set of distinctive country blues songs plus a couple of jazz classics on his aptly named Homage CD (rickrosato/bandcamp.com/album/homage). Applying full intensity to this less-than-23 minute disc, he uses different tunings and mutes to attain the yearning resonation of the original tunes. Throughout his full rounded tone and supple fingering makes up for any lack of accompaniment. Serendipitously he too interprets Crepuscule with Nellie. Remaining mostly in the instrument’s bass clef, he plucks his way though bluesy variations before exposing the theme at the two-thirds mark. Ironically Elvin’s Guitar Blues, composed by powerhouse drummer Elvin Jones, is more highly rhythmic and in context sounds as traditional as the venerable tunes surrounding it. These range from Mississippi John Hurt’s songster classic Boys, You’re Welcome played with a spry guitar-like lilt, to Muddy Waters’ I Can’t Be Satisfied, the epitome of hard blues and harbinger of R&B. On the latter Rosato emphasizes the beat with double and triple strokes and pumped-up theme variations before shaking his way to full theme statement. Overall, he signals his homage and adaptation best on Skip James’ Hard Time Killing Floor Blues. He hammers strings to bend notes and repeats choruses so that the original’s emotional pressure and his distinctive woody vibrations are given equal play.

More of an undertaking, Indian-American vocalist Christine Correa’s Just You Stand and Listen with Me (Sunnyside Records SSC 1684 sunnysiderecords.com) interprets compositions from drummer Max Roach’s 1961 albums We Insist! and Percussion Bitter Sweet that chronicled his militant response to that era’s Civil Rights situation. As on the original discs, the singer’s dramatic personification of the mostly sardonic and defiant lyrics is doubled or commented upon by Sam Newsome’s soprano saxophone, with pianist Andrew Boudreau, bassist Kim Cass and drummer Michael Sarin adding the requisite accompaniment. Studied in guttural expressions, melismatic tone gyrations as well as bel canto euphony, Correa energizes some of the simpler lyrics. More to the point, she brings a proper mixture of sarcasm, fortitude and hopefulness to the songs, which range from the slavery evoking Driva’ Man – where her stabbing lyrics are punctuated by whip-like tambourine slaps – and the hypocrite-indicting Mendacity, to the more hopeful All Africa and Freedom Day. The latter concludes the album proclaiming a program of demand, defiance and realization. The former, like some of the other tracks, expresses its strength in spite of – or perhaps because of – wordless vocalizing. Matching her cadences to drum ruffs, the exposition is bolstered as Sarin adds percussion accents and Newsome treble slides and spits. This leads into Triptych: Prayer/Protest/Peace a protracted essay in blending voice ululations, yodels and murmurs with high-pitched saxophone loops and split tones sounding nearly identical to the voice, with both backed by a slithering bass line and drum clunks. Boudreau’s subtle comping or tinkling swing plus Cass’ thumping bass embellishments are clearly exhibited throughout as group instrumental prowess. Yet sadly the state of the world, and especially the US, make Correa’s recasting of some of the lyrics as relevant in 2023 as 1961.

More of an undertaking, Indian-American vocalist Christine Correa’s Just You Stand and Listen with Me (Sunnyside Records SSC 1684 sunnysiderecords.com) interprets compositions from drummer Max Roach’s 1961 albums We Insist! and Percussion Bitter Sweet that chronicled his militant response to that era’s Civil Rights situation. As on the original discs, the singer’s dramatic personification of the mostly sardonic and defiant lyrics is doubled or commented upon by Sam Newsome’s soprano saxophone, with pianist Andrew Boudreau, bassist Kim Cass and drummer Michael Sarin adding the requisite accompaniment. Studied in guttural expressions, melismatic tone gyrations as well as bel canto euphony, Correa energizes some of the simpler lyrics. More to the point, she brings a proper mixture of sarcasm, fortitude and hopefulness to the songs, which range from the slavery evoking Driva’ Man – where her stabbing lyrics are punctuated by whip-like tambourine slaps – and the hypocrite-indicting Mendacity, to the more hopeful All Africa and Freedom Day. The latter concludes the album proclaiming a program of demand, defiance and realization. The former, like some of the other tracks, expresses its strength in spite of – or perhaps because of – wordless vocalizing. Matching her cadences to drum ruffs, the exposition is bolstered as Sarin adds percussion accents and Newsome treble slides and spits. This leads into Triptych: Prayer/Protest/Peace a protracted essay in blending voice ululations, yodels and murmurs with high-pitched saxophone loops and split tones sounding nearly identical to the voice, with both backed by a slithering bass line and drum clunks. Boudreau’s subtle comping or tinkling swing plus Cass’ thumping bass embellishments are clearly exhibited throughout as group instrumental prowess. Yet sadly the state of the world, and especially the US, make Correa’s recasting of some of the lyrics as relevant in 2023 as 1961.

Taking a detour from established icons to his contemporary, Marc Ducret – Palm Sweat’s Plays the Music of Tim Berne (Screwgun/OOYH 001 outofyourheadrecords.com) has the French guitarist sonically enriching compositions by the American saxophonist whom he has worked with since the mid-1990s. Throughout Ducret, who plays a variety of guitars, basses and hand drums, is backed on and off by brass players Fabrice Martinez and Chrstiane Bopp, flutist Sylvaine Hélary and cellist Bruno Ducret. A variant of Dumitriu’s and Rosato’s solo showpieces, the guitarist used the tools and frequencies available in his home recording studio to multi-track his playing on various instruments then mixed the results, later adding other musicians’ contributions. Neither auto-tuning nor artificial intelligence, the multiple Ducrets heard produce an organic aggregate that snugly bonds spatial and spectral elements. This is obvious from Curls/Palm Sweat/Mirth of the Cool, the triptych first track that logically moves from electric guitar fuzz tones that migrate across the sound space to become dissonant when backed by secondary guitar riffs. Rooted bass guitar strums linked to frame drum ruffs provide a rhythm that underscores the performance, which reaches a high point as a pleasant finger-style melody is answered by high-pitched string frails. Broken up by sequences where guitar interludes suggest hesitant mandolin-like hard picking or primitivist folksy strums, this approach is used throughout the session. Development of Berne’s themes is linked to techniques as varied as sophisticated slurred fingering, intense string hammering, a pivot to hard rock-like screaming flanges and even jagged strokes on Rolled Oats that sound as if a Thelonious Monk motif has been transferred to the guitar. For added variety, these distinctive frails or chordal development are sometimes cushioned by vamps from the entire horn section to fill in dangling spaces. Bopp’s echoing trombone-plunger tones add portamento resonance to Shiteless which is otherwise given over to a string mash-up among chiming smacks, lyrical acoustic asides and buzzsaw electric riffs. The session’s real climax occurs on Static, as Martinez’s trumpet smears and open-horn flutters are a contradictory harbinger to a squeezed cello-guitar conclusion that almost sounds like an Eastern European dance and is further emphasized with wordless vocalizing and hand clapping.

Taking a detour from established icons to his contemporary, Marc Ducret – Palm Sweat’s Plays the Music of Tim Berne (Screwgun/OOYH 001 outofyourheadrecords.com) has the French guitarist sonically enriching compositions by the American saxophonist whom he has worked with since the mid-1990s. Throughout Ducret, who plays a variety of guitars, basses and hand drums, is backed on and off by brass players Fabrice Martinez and Chrstiane Bopp, flutist Sylvaine Hélary and cellist Bruno Ducret. A variant of Dumitriu’s and Rosato’s solo showpieces, the guitarist used the tools and frequencies available in his home recording studio to multi-track his playing on various instruments then mixed the results, later adding other musicians’ contributions. Neither auto-tuning nor artificial intelligence, the multiple Ducrets heard produce an organic aggregate that snugly bonds spatial and spectral elements. This is obvious from Curls/Palm Sweat/Mirth of the Cool, the triptych first track that logically moves from electric guitar fuzz tones that migrate across the sound space to become dissonant when backed by secondary guitar riffs. Rooted bass guitar strums linked to frame drum ruffs provide a rhythm that underscores the performance, which reaches a high point as a pleasant finger-style melody is answered by high-pitched string frails. Broken up by sequences where guitar interludes suggest hesitant mandolin-like hard picking or primitivist folksy strums, this approach is used throughout the session. Development of Berne’s themes is linked to techniques as varied as sophisticated slurred fingering, intense string hammering, a pivot to hard rock-like screaming flanges and even jagged strokes on Rolled Oats that sound as if a Thelonious Monk motif has been transferred to the guitar. For added variety, these distinctive frails or chordal development are sometimes cushioned by vamps from the entire horn section to fill in dangling spaces. Bopp’s echoing trombone-plunger tones add portamento resonance to Shiteless which is otherwise given over to a string mash-up among chiming smacks, lyrical acoustic asides and buzzsaw electric riffs. The session’s real climax occurs on Static, as Martinez’s trumpet smears and open-horn flutters are a contradictory harbinger to a squeezed cello-guitar conclusion that almost sounds like an Eastern European dance and is further emphasized with wordless vocalizing and hand clapping.

It isn’t only classical jazz themes which are reinterpreted by creative musicians, so-called classical music is part of a retrofit as well. The Rite of Spring – Spectre d’un songe (Pyroclastic Records PR 26 pyroclasticrecords.com) came about after the family of Igor Stravinsky insisted that any piano performance of the famous 1913 ballet and orchestral concert work had to be played by two pianists. Swiss pianist Sylvie Courvoisier had already created a solo version of the composition. She then recruited American pianist Cory Smythe, who has experience similar to her own, playing improvised and notated music, to perform and record the two movements of Rite and her own Spectre d’un songe. The key to this disc is that the two pianists are so cognizant of the source that they’re not creating improvisations on, but improvisations along with, the Stravinsky score. The performance isn’t a miniaturization of the composition, but a particular diversification of it. During Le Sacre du Printemps, Pt.1: The Adoration of the Earth and Le Sacre du Printemps, Pt.2: The Sacrifice they use tropes encompassing bright keyboard bounces, high-pitched glissandi, crescendos of rolling notes and pedal- point pressure, but don’t neglect the underlying theme. Passing motifs between them or having one decorate a line as the other impels the theme, the enhanced rhythmic pressure or lyrical sequences always refer back to the original composition. Throughout, the familiar motif frequently appears and reappears and is expressed without extemporization at the end. Courvoisier’s Spectre d’un songe which takes up as much space as both Stravinsky tracks isn’t really ghostly or dream-like. Instead, its droning andante exposition is toughened through inner string reverberations and bass clef emphasis to double in tempo and loudness by mid-section. As the sequence sways while each keyboardist interjects key clips, clanks and cascades, it diverts into rumbles and pressure, but like the previous notated piece never loses the narrative thrust. A slow methodical examination of each note and pattern typifies the final section, which refers back to the introduction as it fades away.

It isn’t only classical jazz themes which are reinterpreted by creative musicians, so-called classical music is part of a retrofit as well. The Rite of Spring – Spectre d’un songe (Pyroclastic Records PR 26 pyroclasticrecords.com) came about after the family of Igor Stravinsky insisted that any piano performance of the famous 1913 ballet and orchestral concert work had to be played by two pianists. Swiss pianist Sylvie Courvoisier had already created a solo version of the composition. She then recruited American pianist Cory Smythe, who has experience similar to her own, playing improvised and notated music, to perform and record the two movements of Rite and her own Spectre d’un songe. The key to this disc is that the two pianists are so cognizant of the source that they’re not creating improvisations on, but improvisations along with, the Stravinsky score. The performance isn’t a miniaturization of the composition, but a particular diversification of it. During Le Sacre du Printemps, Pt.1: The Adoration of the Earth and Le Sacre du Printemps, Pt.2: The Sacrifice they use tropes encompassing bright keyboard bounces, high-pitched glissandi, crescendos of rolling notes and pedal- point pressure, but don’t neglect the underlying theme. Passing motifs between them or having one decorate a line as the other impels the theme, the enhanced rhythmic pressure or lyrical sequences always refer back to the original composition. Throughout, the familiar motif frequently appears and reappears and is expressed without extemporization at the end. Courvoisier’s Spectre d’un songe which takes up as much space as both Stravinsky tracks isn’t really ghostly or dream-like. Instead, its droning andante exposition is toughened through inner string reverberations and bass clef emphasis to double in tempo and loudness by mid-section. As the sequence sways while each keyboardist interjects key clips, clanks and cascades, it diverts into rumbles and pressure, but like the previous notated piece never loses the narrative thrust. A slow methodical examination of each note and pattern typifies the final section, which refers back to the introduction as it fades away.

In their own ways each of the musicians confirms that all sorts of music composed by many musicians of very different attitudes can be interpreted in an uncommon and individual fashion. And they go on to demonstrate that.

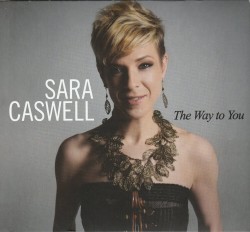

The Way to You (violin jazz)

The Way to You (violin jazz)