Much of what we define as jazz and improvised music has been driven by rhythmic changes established by innovative percussionists. Yet very little that transpired was the result of single Eureka moments propelled by one individual. Each contemporary advance strengthened the next ones, with some percussionists operating far apart creating important advances not acknowledged until later. Proof of their creative skills and later acceptance is demonstrated on these mostly recently discovered sessions.

Arguably the most crucial disc here is Stop Time (NoBusiness Records NBCD 163 nobusinessrecords.com), a 1978 New York City live date by three sound architects who never recorded together before or afterwards. Key to the disc is the sympathetic, sophisticated yet strong accents of drummer Barry Altschul (b.1943), who by that time had perfected the melding of hard bop power with free jazz multiple tempos that he used with everyone from Paul Bley to Anthony Braxton. His associates were David Izenson (1932-1979), famous as a member of Ornette Coleman’s trio and clarinetist Perry Robinson (1938-2018), whose style encompassed elements of folk, Klezmer, abstract and notated music. Robins on, who was in groups headed by leaders as diverse as Dave Brubeck and William Parker, unites the four untitled improvisations with melodic trills and flutters, interjected squeaks and circular squeals and miniature reed bites. Izenson’s arco variations are often tinged with melancholy and confidently work up the scale, while his pizzicato work expands with triple stopping patterns. Yet his turns to walking or positioned thumps preserve linear motion along with Altschul’s backbeat. Conventional enough to trade fours with the clarinetist during Untitled I, the drummer turns on percussion razzle dazzle with paradiddles, flashy strokes and fanciful patterning on the last track. But his backbeat aids in connecting the clarinetist’s strained tonguing, clarion twitters and intense flattement away from sharp yelps into responsive swing by the finale. Probably the most telling sequence that confirms the trio’s sound evolution along takes place during the last section of Untitled III. Suddenly Robinson’s reconfigured tongue stops and slurs become a blues line, accompanied by string strums and drum shuffles. Rhythm blends with reconstitution as reed split tones and doits are interspaced among long-lined flutters and Izenson’s jagged arco swipes that alternate with rhythmic double and triple stopping.

Arguably the most crucial disc here is Stop Time (NoBusiness Records NBCD 163 nobusinessrecords.com), a 1978 New York City live date by three sound architects who never recorded together before or afterwards. Key to the disc is the sympathetic, sophisticated yet strong accents of drummer Barry Altschul (b.1943), who by that time had perfected the melding of hard bop power with free jazz multiple tempos that he used with everyone from Paul Bley to Anthony Braxton. His associates were David Izenson (1932-1979), famous as a member of Ornette Coleman’s trio and clarinetist Perry Robinson (1938-2018), whose style encompassed elements of folk, Klezmer, abstract and notated music. Robins on, who was in groups headed by leaders as diverse as Dave Brubeck and William Parker, unites the four untitled improvisations with melodic trills and flutters, interjected squeaks and circular squeals and miniature reed bites. Izenson’s arco variations are often tinged with melancholy and confidently work up the scale, while his pizzicato work expands with triple stopping patterns. Yet his turns to walking or positioned thumps preserve linear motion along with Altschul’s backbeat. Conventional enough to trade fours with the clarinetist during Untitled I, the drummer turns on percussion razzle dazzle with paradiddles, flashy strokes and fanciful patterning on the last track. But his backbeat aids in connecting the clarinetist’s strained tonguing, clarion twitters and intense flattement away from sharp yelps into responsive swing by the finale. Probably the most telling sequence that confirms the trio’s sound evolution along takes place during the last section of Untitled III. Suddenly Robinson’s reconfigured tongue stops and slurs become a blues line, accompanied by string strums and drum shuffles. Rhythm blends with reconstitution as reed split tones and doits are interspaced among long-lined flutters and Izenson’s jagged arco swipes that alternate with rhythmic double and triple stopping.

Skip forward two and a half years to hear how a contemporary European percussionist advanced textural beats. Borne on a Whim Duets, 1981 (Corbett vs Dempsey CvsDCD100 corbettvsdempsey.com), is a series of duets between British drummer Paul Lytton (b.1947), who also uses live electronics, and German Erhard Hirt (b.1951), playing electric guitar and dobro. Lytton, known for his work with Evan Parker, and Hirt, who often plays in larger configurations, had by this point perfected the ability to strip down music to its core without affecting its essence and flow. The definition of lower-case improv, Lytton’s often segregated and positioned clanks, near-silent brush wipes and rim and cymbal rustles outline the sonic landscape alongside Hirt’s single-string stops, taunt frails and rapid twangs, with intermittent voltage oscillations filling the remaining spaces. Tracks are built with jagged guitar stabs and explorations up to the tuning pegs balanced by positioned ruffs and brief mylar resonations. Sometimes vibrations occur in tandem, other times they evolve separately, adhering and fragmenting like amoebas. At 27 minutes, nearly double in length than any other track, The Sensitive Stickler, is the CD’s tour-de-force. Gradually increasing in volume, drum expression moves from subtle metallic shakes and brief electronic warbles to broad wood pops, bell pings and cymbal clangs as the guitarist does the same, torquing single-note strains to continuous string shuffles and dial-twisting squeaks. With nuance, the exposition shifts again during the final sequence as the tune is brought to a convivial finale with delicate drumstick shakes and shuffles first set off rugged guitar flanges and string buzzes so that Hirt’s subsequent disconnected dobro licks meet appropriate slaps and paradiddles from Lytton.

Skip forward two and a half years to hear how a contemporary European percussionist advanced textural beats. Borne on a Whim Duets, 1981 (Corbett vs Dempsey CvsDCD100 corbettvsdempsey.com), is a series of duets between British drummer Paul Lytton (b.1947), who also uses live electronics, and German Erhard Hirt (b.1951), playing electric guitar and dobro. Lytton, known for his work with Evan Parker, and Hirt, who often plays in larger configurations, had by this point perfected the ability to strip down music to its core without affecting its essence and flow. The definition of lower-case improv, Lytton’s often segregated and positioned clanks, near-silent brush wipes and rim and cymbal rustles outline the sonic landscape alongside Hirt’s single-string stops, taunt frails and rapid twangs, with intermittent voltage oscillations filling the remaining spaces. Tracks are built with jagged guitar stabs and explorations up to the tuning pegs balanced by positioned ruffs and brief mylar resonations. Sometimes vibrations occur in tandem, other times they evolve separately, adhering and fragmenting like amoebas. At 27 minutes, nearly double in length than any other track, The Sensitive Stickler, is the CD’s tour-de-force. Gradually increasing in volume, drum expression moves from subtle metallic shakes and brief electronic warbles to broad wood pops, bell pings and cymbal clangs as the guitarist does the same, torquing single-note strains to continuous string shuffles and dial-twisting squeaks. With nuance, the exposition shifts again during the final sequence as the tune is brought to a convivial finale with delicate drumstick shakes and shuffles first set off rugged guitar flanges and string buzzes so that Hirt’s subsequent disconnected dobro licks meet appropriate slaps and paradiddles from Lytton.

Another duo that expresses percussion ambidextrousness and the adaptation of another country’s drum tradition to creative music is featured on Triangle, Live at OHM 1987 (NoBusiness Records NBCD 160 nobusinessrecords.com). Recorded in Tokyo, the selection details how Sabu Toyozumi (b.1943), a first generation Japanese free jazzer, who has worked with numerous local, European and American creators during his 60-year career, intersected with German tenor saxophonist/tárogató player Peter Brötzmann (1941-2023), whose take-no-prisoners approach is musically fiercer than the bellicose activities of either of these players’ countries prior to and during World War II. Reflecting, but not copying the power and theatricalism of Taiko drumming, Toyozumi confirms that style’s birth from jazz drumming and quickly marshals clip clops and clatters into a pseudo military pace that easily matches Brötzmann’s Teutonic altissimo runs and snarling overblowing. The saxophonist not only advances broken octave textures in all saxophone pitches, but at times, such as during Triangle and Valentine Chocolate, switches to woody tárogató whose gentling reed trills are ably met by the drummer’s carefully positioned palms-on-drum-top slaps and temple-bell-like plinks. Although the emotionalism implicit in Brötzmann’s solos sometimes causes him to momentarily turn away from the mics, there’s no stopping his molten flow of inspiration. The session is completed during Peter & Sabu’s Points as Toyozumi sounds out a contrapuntal collection of paradiddles and smacks to meet the unbridled thrust of spectrofluctuation and multi-sectional screams from Brötzmann’s horn. Note though that throughout the extended Depth of Focus as irregular split tones and jagged bites issue from the saxophonist, the drummer emulates both western and eastern percussion with metallic cross pops interrupted at points with miniature gong resonations.

Another duo that expresses percussion ambidextrousness and the adaptation of another country’s drum tradition to creative music is featured on Triangle, Live at OHM 1987 (NoBusiness Records NBCD 160 nobusinessrecords.com). Recorded in Tokyo, the selection details how Sabu Toyozumi (b.1943), a first generation Japanese free jazzer, who has worked with numerous local, European and American creators during his 60-year career, intersected with German tenor saxophonist/tárogató player Peter Brötzmann (1941-2023), whose take-no-prisoners approach is musically fiercer than the bellicose activities of either of these players’ countries prior to and during World War II. Reflecting, but not copying the power and theatricalism of Taiko drumming, Toyozumi confirms that style’s birth from jazz drumming and quickly marshals clip clops and clatters into a pseudo military pace that easily matches Brötzmann’s Teutonic altissimo runs and snarling overblowing. The saxophonist not only advances broken octave textures in all saxophone pitches, but at times, such as during Triangle and Valentine Chocolate, switches to woody tárogató whose gentling reed trills are ably met by the drummer’s carefully positioned palms-on-drum-top slaps and temple-bell-like plinks. Although the emotionalism implicit in Brötzmann’s solos sometimes causes him to momentarily turn away from the mics, there’s no stopping his molten flow of inspiration. The session is completed during Peter & Sabu’s Points as Toyozumi sounds out a contrapuntal collection of paradiddles and smacks to meet the unbridled thrust of spectrofluctuation and multi-sectional screams from Brötzmann’s horn. Note though that throughout the extended Depth of Focus as irregular split tones and jagged bites issue from the saxophonist, the drummer emulates both western and eastern percussion with metallic cross pops interrupted at points with miniature gong resonations.

While the other percussionists here express their mature styles, The Milwaukee Tapes, Vol.2 (Corbett vs Dempsey CvsDCD101 corbettvsdempsey.com) from 1980 is noteworthy since it’s an early example of the accomplishments of Hamid Drake (b.1955), one of this century’s pre-eminent percussionists. Then known as Hank, Drake’s dextrous playing is a key element of this live date, headlined by AACM tenor master Fred Anderson (1929-2010) and featuring both men’s long-time associate trumpeter Billy Brimfield (1938-2012) and the little-known bassist Larry Hayrod. Overall, the program usually involves the two horns harmonizing on the theme, then opening it up for freeform solos as a powerful bass line and percussion resonations respond to each challenge. The rhythm section on Our Theme for instance rumbles and rambles as Brimfield’s emphatic half-valve exploration abuts Anderson’s harsh widening reed slurs. Drake’s smacks, bangs and rebounds gradually speed up the tempo, acknowledging Anderson’s distinctive accelerations. Each player follows the narrative’s descending arc before wrapping up with a comforting sound cluster. Bernice follows a similar linear association as the trumpeter’s portamento storytelling brings out Drake’s rim shots that solidify the overall swinging beat. Later, the bassist’s vibrating shakes provide a solid foundation for the others’ timbral explorations. Wedded firmly to Free Jazz as the Stop Time trio mentioned above, the Midwestern ensemble’s output is tougher, bluesier and unaffected by European influences. Still Drake’s quick responses to Brimfield’s sometime unexpected brass triplets and Anderson’s idiosyncratic Woody Woodpecker-like yelps and eviscerating split-tone bites with hard thumps, press rolls and Latin inferences augur his future percussion sophistication in any situation.

While the other percussionists here express their mature styles, The Milwaukee Tapes, Vol.2 (Corbett vs Dempsey CvsDCD101 corbettvsdempsey.com) from 1980 is noteworthy since it’s an early example of the accomplishments of Hamid Drake (b.1955), one of this century’s pre-eminent percussionists. Then known as Hank, Drake’s dextrous playing is a key element of this live date, headlined by AACM tenor master Fred Anderson (1929-2010) and featuring both men’s long-time associate trumpeter Billy Brimfield (1938-2012) and the little-known bassist Larry Hayrod. Overall, the program usually involves the two horns harmonizing on the theme, then opening it up for freeform solos as a powerful bass line and percussion resonations respond to each challenge. The rhythm section on Our Theme for instance rumbles and rambles as Brimfield’s emphatic half-valve exploration abuts Anderson’s harsh widening reed slurs. Drake’s smacks, bangs and rebounds gradually speed up the tempo, acknowledging Anderson’s distinctive accelerations. Each player follows the narrative’s descending arc before wrapping up with a comforting sound cluster. Bernice follows a similar linear association as the trumpeter’s portamento storytelling brings out Drake’s rim shots that solidify the overall swinging beat. Later, the bassist’s vibrating shakes provide a solid foundation for the others’ timbral explorations. Wedded firmly to Free Jazz as the Stop Time trio mentioned above, the Midwestern ensemble’s output is tougher, bluesier and unaffected by European influences. Still Drake’s quick responses to Brimfield’s sometime unexpected brass triplets and Anderson’s idiosyncratic Woody Woodpecker-like yelps and eviscerating split-tone bites with hard thumps, press rolls and Latin inferences augur his future percussion sophistication in any situation.

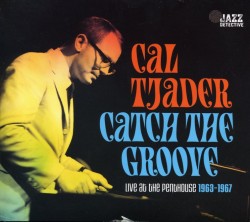

Although Catch The Groove: Live At The Penthouse (1963-1967) (Jazz Detective DDJD-012 cal-tjader.bandcamp.com/album/catch-the-groove-live-at-the-penthouse-1963-1967) dates from a mere decade before the other discs, the two-CD set could be from another musical planet. That’s because the quintets led by vibraphone player Cal Tjader are firmly implanted in the commercial music business that the other sessions transcended. However, the 27 tracks recorded during several dates at a Seattle night club are just as crucial to percussion evolution. Tjader (1925–1982) was the most prominent non-Hispanic musician with impeccable jazz credentials – early on he was Dave Brubeck’s drummer – to confirm the adaptability of Latin rhythms to creative music. Although fewer than half the tracks have obvious Latin titles, all include some aspects of the montuno style. That means the group’s kit drummer also plays timbales and on five of the six dates another percussionist, Armando Peraza, is added playing bongos and congas. While the quintet’s nightclub repertoire included ballads like Shadow of Your Smile, interpretations with faultless swing of everything from Bags’ Groove to Along Comes Mary, Tjadar’s individuality is best expressed on the Latin tunes. Throughout, he and his exceptional associates – which at points include pianist Clare Fischer and bassist Monk Montgomery – help solidify a sound that’s midway between a Cuban conjunto and a modern jazz combo. Responsive piano tinkling, mostly played by Lonnie Hewitt, confirms the blues and rhythm underpinning of most tunes; the piano-vibe interface is jazzy and improvised connections are constantly speedier and stretch past Latin conventions even if the base comes from expected riffs as on Maramoor Mombo or the standard Cuban Fantasy. Mambo Inn even includes a quote from Salt Peanuts. At the same time the bassists’ constant use of the expected tumbao patterns and tick-tock rhythmic breaks during expositions imbue even the most languid ballad with an Afro-Cuban tinge.

Although Catch The Groove: Live At The Penthouse (1963-1967) (Jazz Detective DDJD-012 cal-tjader.bandcamp.com/album/catch-the-groove-live-at-the-penthouse-1963-1967) dates from a mere decade before the other discs, the two-CD set could be from another musical planet. That’s because the quintets led by vibraphone player Cal Tjader are firmly implanted in the commercial music business that the other sessions transcended. However, the 27 tracks recorded during several dates at a Seattle night club are just as crucial to percussion evolution. Tjader (1925–1982) was the most prominent non-Hispanic musician with impeccable jazz credentials – early on he was Dave Brubeck’s drummer – to confirm the adaptability of Latin rhythms to creative music. Although fewer than half the tracks have obvious Latin titles, all include some aspects of the montuno style. That means the group’s kit drummer also plays timbales and on five of the six dates another percussionist, Armando Peraza, is added playing bongos and congas. While the quintet’s nightclub repertoire included ballads like Shadow of Your Smile, interpretations with faultless swing of everything from Bags’ Groove to Along Comes Mary, Tjadar’s individuality is best expressed on the Latin tunes. Throughout, he and his exceptional associates – which at points include pianist Clare Fischer and bassist Monk Montgomery – help solidify a sound that’s midway between a Cuban conjunto and a modern jazz combo. Responsive piano tinkling, mostly played by Lonnie Hewitt, confirms the blues and rhythm underpinning of most tunes; the piano-vibe interface is jazzy and improvised connections are constantly speedier and stretch past Latin conventions even if the base comes from expected riffs as on Maramoor Mombo or the standard Cuban Fantasy. Mambo Inn even includes a quote from Salt Peanuts. At the same time the bassists’ constant use of the expected tumbao patterns and tick-tock rhythmic breaks during expositions imbue even the most languid ballad with an Afro-Cuban tinge.

Some percussion implement was likely primitive human’s first musical instrument. Its evolution has been in lockstep with humanity itself. Theses previously unreleased sounds provide more exact examples as how the beat goes on.