Historical gap filling, bringing back into circulation almost unknown sessions or offering new audiences a chance to experience classics, the appearance of improvised music reissues and rediscoveries continues unabated. Some sessions include additional material or entire programs which were thought to never have been recorded. This 1960s and 1970s selection offers instances of all of these things.

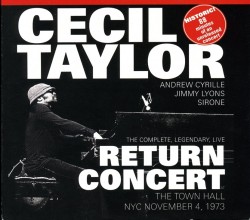

The most important semi-reissue is The Complete, Legendary, Live Return Concert (Oblivion Records OD-08 oblivionrecords.co), which marked pianist Cecil Taylor’s return to performance after five years in academia. The date, which featured Taylor with regular associates, alto saxophonist Jimmy Lyons, drummer Andrew Cyrille and bassist Sirone, was celebrated when released as a limited edition LP. Complete is just that, however, for besides offering the nearly 38-minute solo and quartet music that made up the initial Spring of Two Blue-J’s, this two-CD set adds an 88-minute quartet performance of Autumn/Parade from the concert. It’s impossible to add superlatives to describe the original. The mature Taylor style had crystalized and throughout his solo excursion, he works every part of the piano, with forceful hammering on the lowest-pitched keys all the way up to responsive glissandi in the upper registers. Even as he’s creating mountains of notes, his emphasized dynamics manage to be Impressionistic, linear and true to the initial theme. Narrative reflections abound on the supple interface that was the original quartet track. Starting slowly, upward and downward piano flourishes are accompanied by fluid double bass pacing and resounding drum pops. Meanwhile Lyons picks up the theme and gradually repeats it, with each pass becoming more vigorous, as multiphonics, flattement, tongue stops and altissimo runs are added. When his distinct meld of freebop and energy music are crammed into a heavily vibrating climax, the others join with similar intensity only to downshift to responsive vibrations following a decisive Sirone string pluck. This, plus an intense free music elaboration, is expressed during the new section. Working off Cyrille’s pops and Sirone’s pumps, Taylor repeatedly shatters the infrastructure, with continuous affiliations, cleanly articulating the introduction as Lyons gathers strength with Woody Woodpecker-like bites and split-tone cries. Percussive piano jabs spur the saxophonist to clarion screeches, expressing yearning as well as power. Each time, contrasting piano dynamics or interjections from the others threaten to fragment the narrative, thematic motifs, usually from Taylor, reappear and confirm horizontal movement. Eye-blink transitions are commonplace, with interludes of unexpectedly gentle runs preventing overall murkiness. Rhythm isn’t neglected either, as cymbal crashes or string pops suggest backend power. By mid-point spectacular asides, detours and flourishes affirm Taylor’s stylistic singleness, yet these rugged cascades also energetically extend the theme. Taylor’s galloping prestissimo asides at the three-quarter mark encourage Lyons to ascend to the sopranissimo range. The concluding section is studded with note flurries from the piano as Sirone’s careful string stops and Cyrille’s drum ruffs centre the proceedings. With Lyons back for rugged tongue slaps, Taylor broadens the interface with theme repetitions before a high-energy finale.

The most important semi-reissue is The Complete, Legendary, Live Return Concert (Oblivion Records OD-08 oblivionrecords.co), which marked pianist Cecil Taylor’s return to performance after five years in academia. The date, which featured Taylor with regular associates, alto saxophonist Jimmy Lyons, drummer Andrew Cyrille and bassist Sirone, was celebrated when released as a limited edition LP. Complete is just that, however, for besides offering the nearly 38-minute solo and quartet music that made up the initial Spring of Two Blue-J’s, this two-CD set adds an 88-minute quartet performance of Autumn/Parade from the concert. It’s impossible to add superlatives to describe the original. The mature Taylor style had crystalized and throughout his solo excursion, he works every part of the piano, with forceful hammering on the lowest-pitched keys all the way up to responsive glissandi in the upper registers. Even as he’s creating mountains of notes, his emphasized dynamics manage to be Impressionistic, linear and true to the initial theme. Narrative reflections abound on the supple interface that was the original quartet track. Starting slowly, upward and downward piano flourishes are accompanied by fluid double bass pacing and resounding drum pops. Meanwhile Lyons picks up the theme and gradually repeats it, with each pass becoming more vigorous, as multiphonics, flattement, tongue stops and altissimo runs are added. When his distinct meld of freebop and energy music are crammed into a heavily vibrating climax, the others join with similar intensity only to downshift to responsive vibrations following a decisive Sirone string pluck. This, plus an intense free music elaboration, is expressed during the new section. Working off Cyrille’s pops and Sirone’s pumps, Taylor repeatedly shatters the infrastructure, with continuous affiliations, cleanly articulating the introduction as Lyons gathers strength with Woody Woodpecker-like bites and split-tone cries. Percussive piano jabs spur the saxophonist to clarion screeches, expressing yearning as well as power. Each time, contrasting piano dynamics or interjections from the others threaten to fragment the narrative, thematic motifs, usually from Taylor, reappear and confirm horizontal movement. Eye-blink transitions are commonplace, with interludes of unexpectedly gentle runs preventing overall murkiness. Rhythm isn’t neglected either, as cymbal crashes or string pops suggest backend power. By mid-point spectacular asides, detours and flourishes affirm Taylor’s stylistic singleness, yet these rugged cascades also energetically extend the theme. Taylor’s galloping prestissimo asides at the three-quarter mark encourage Lyons to ascend to the sopranissimo range. The concluding section is studded with note flurries from the piano as Sirone’s careful string stops and Cyrille’s drum ruffs centre the proceedings. With Lyons back for rugged tongue slaps, Taylor broadens the interface with theme repetitions before a high-energy finale.

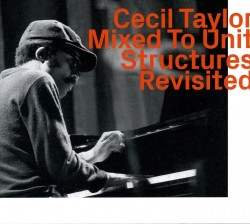

While they’re also important building blocks in the Taylor oeuvre, by the standards of 1973, the sessions from 1961 and 1966 collected as Cecil Taylor Mixed to Unit Structures Revisited (ezz-thetics 1110 hathut.com) aren’t shatteringly intense. While thought radical for the times there are points during the three 1961 tracks where the combination of walking bass, piano vamps and Lyons’ soloing with Charlie Parker-like contours could describe a bebop session. As a septet, the group opens up on the concluding Mixed. Its slackened pace with Ellington-like voicings contrasts floating smears from trombonist Roswell Rudd and trumpeter Ted Curson with split tone vamps from Lyons and tenor saxophonist Archie Shepp. Even Taylor’s flowing pianism is more pastel than percussive. With a different septet, the mature Taylor archetype with dynamic shudders and unexpected turns comes into focus by 1966. As three horns screech, smear and scoop and the two basses buzz, the pianist’s vigorous runs are continuously present. A rare sidebar to Taylor’s composing, Enter, Evening (Soft Line Structure) features an unexpected jazz-world music suggestion with Ken McIntyre’s oboe and Henry Grimes or Alan Silva’s bass producing ney-like and oud-like textures. Improv wins out with trumpeter Eddie Gale’s shakes and the saxophonists’ smears playing elevated pitches. The title track oscillates between freebop and free jazz with the horn parts leaping from call-and-response riffs to encircling cawing vibrations with brassy triplets pushing the energy still higher. Tellingly though, the pianist’s dynamic stop-time crunches and stride in his duet with Cyrille on the concluding Tales (8 Whisps) is a mirror image of how the two would play in 1973.

While they’re also important building blocks in the Taylor oeuvre, by the standards of 1973, the sessions from 1961 and 1966 collected as Cecil Taylor Mixed to Unit Structures Revisited (ezz-thetics 1110 hathut.com) aren’t shatteringly intense. While thought radical for the times there are points during the three 1961 tracks where the combination of walking bass, piano vamps and Lyons’ soloing with Charlie Parker-like contours could describe a bebop session. As a septet, the group opens up on the concluding Mixed. Its slackened pace with Ellington-like voicings contrasts floating smears from trombonist Roswell Rudd and trumpeter Ted Curson with split tone vamps from Lyons and tenor saxophonist Archie Shepp. Even Taylor’s flowing pianism is more pastel than percussive. With a different septet, the mature Taylor archetype with dynamic shudders and unexpected turns comes into focus by 1966. As three horns screech, smear and scoop and the two basses buzz, the pianist’s vigorous runs are continuously present. A rare sidebar to Taylor’s composing, Enter, Evening (Soft Line Structure) features an unexpected jazz-world music suggestion with Ken McIntyre’s oboe and Henry Grimes or Alan Silva’s bass producing ney-like and oud-like textures. Improv wins out with trumpeter Eddie Gale’s shakes and the saxophonists’ smears playing elevated pitches. The title track oscillates between freebop and free jazz with the horn parts leaping from call-and-response riffs to encircling cawing vibrations with brassy triplets pushing the energy still higher. Tellingly though, the pianist’s dynamic stop-time crunches and stride in his duet with Cyrille on the concluding Tales (8 Whisps) is a mirror image of how the two would play in 1973.

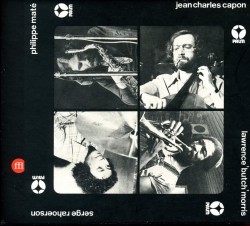

Free jazz had become part of global musical language by the mid-1970s. Yet, as it was being diffused, non-Americans were making their own additions to its spread. Case in point is this reissue of the eponymous recording Jean-Charles Capon/Philippe Maté/Lawrence “Butch” Morris/Serge Rahoerson (Souffle Continu Records FFL072 soufflecontinurecords.com), from 1976 that succinctly highlights some of the music’s future directions. American cornetist Morris was part of the free jazz fraternity and his plunger tone, mercurial obbligatos and rhythmic asides confirm that. With deep digging solos, tenor saxophonist Maté adds French free music. But Gallic cellist Capon was part of the Baroque Jazz Trio, a studio habitué and had played in Madagascar with local Malagasy musicians, including drummer Rahoerson, who is featured here. Not only can one sense the strands of jazz-world music suggested by Taylor’s Unit Stuctures being woven, but since the rhythm section was recorded first with the horn players’ sounds added later, future studio sound design is also in use. Despite the separation, cleavage is practically non-existent. The drummer’s shuffles, slides and cymbal accents fit perfectly, and throughout Capon uses his cello to create the determined pulse of a double bass line. With overdubbing, his pinpointed cello strokes add force to the narratives as he creates spiccato lines as facile as if he were playing violin. Other times, most prominently on Mode De Fa, Capon’s his light pizzicato finesse adds guitar-like sounds to the front line. There’s even a hint of electronic oscillations on Orly-Ivato. Fanciful in parts, funky in others, the disc is more than a blueprint for future musical fusion trends. It’s also a fine contemporary sounding program.

Free jazz had become part of global musical language by the mid-1970s. Yet, as it was being diffused, non-Americans were making their own additions to its spread. Case in point is this reissue of the eponymous recording Jean-Charles Capon/Philippe Maté/Lawrence “Butch” Morris/Serge Rahoerson (Souffle Continu Records FFL072 soufflecontinurecords.com), from 1976 that succinctly highlights some of the music’s future directions. American cornetist Morris was part of the free jazz fraternity and his plunger tone, mercurial obbligatos and rhythmic asides confirm that. With deep digging solos, tenor saxophonist Maté adds French free music. But Gallic cellist Capon was part of the Baroque Jazz Trio, a studio habitué and had played in Madagascar with local Malagasy musicians, including drummer Rahoerson, who is featured here. Not only can one sense the strands of jazz-world music suggested by Taylor’s Unit Stuctures being woven, but since the rhythm section was recorded first with the horn players’ sounds added later, future studio sound design is also in use. Despite the separation, cleavage is practically non-existent. The drummer’s shuffles, slides and cymbal accents fit perfectly, and throughout Capon uses his cello to create the determined pulse of a double bass line. With overdubbing, his pinpointed cello strokes add force to the narratives as he creates spiccato lines as facile as if he were playing violin. Other times, most prominently on Mode De Fa, Capon’s his light pizzicato finesse adds guitar-like sounds to the front line. There’s even a hint of electronic oscillations on Orly-Ivato. Fanciful in parts, funky in others, the disc is more than a blueprint for future musical fusion trends. It’s also a fine contemporary sounding program.

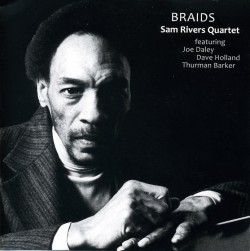

No advance remains static and by 1979, when Braids (NoBusiness NBCD 138 nobusinessrecords.com), this newly discovered Hamburg concert by the Sam Rivers Quartet was recorded, modification to vigorous improvising had been adopted. Not only is one member of the otherwise American band British, but Dave Holland plays both bass and cello. This matches Rivers’ solos on tenor and soprano saxophones, flute and piano. Furthermore, while Thurman Barker plays standard drum kit, the group’s fourth member is Joe Daley, whose sophisticated dexterity on tuba and euphonium means he takes both accompanying and frontline roles. The first part of the concert resembles 1960s energy music as the saxophonist propels split-tone screams and bugling reed bites, backed by thick drum resonations and a fluid bass pulse. Soon a tuba obbligato signals a shift as the tempo balances between allegro and andante, with Rivers’ triple tonguing complemented by the tubist’s portamento effects, finally climax with stretched reed tones and brass grace notes. What elsewhere would be a standard drum solo in pseudo-march tempo actually serves as an introduction to a piano interlude, expressed with contrasting dynamics and varied tempos. Piano patterning squirms forward until speedy rips from Daley change the narrative course. Playing with the swift facility of a valve trombonist, Daley bounces from treble sheets of sound to guttural scoops. Holland’s subsequent strums and ascending string plucks make way for an Arcadian but tough duet between Daley’s tuba puffs and Rivers’ flute peeps. Except for forays into screech mode, the remainder of the flute section opens the narrative to out-and-out swing. Holland’s cello plucks and Barker’s concise small cymbal pings confirm the motion. Kept from any suggestion of prettiness however, the concluding tremolo flute flutters are in sync with Daley’s tuba burbles as rhythmic groove and sound exploration are simultaneously affirmed.

No advance remains static and by 1979, when Braids (NoBusiness NBCD 138 nobusinessrecords.com), this newly discovered Hamburg concert by the Sam Rivers Quartet was recorded, modification to vigorous improvising had been adopted. Not only is one member of the otherwise American band British, but Dave Holland plays both bass and cello. This matches Rivers’ solos on tenor and soprano saxophones, flute and piano. Furthermore, while Thurman Barker plays standard drum kit, the group’s fourth member is Joe Daley, whose sophisticated dexterity on tuba and euphonium means he takes both accompanying and frontline roles. The first part of the concert resembles 1960s energy music as the saxophonist propels split-tone screams and bugling reed bites, backed by thick drum resonations and a fluid bass pulse. Soon a tuba obbligato signals a shift as the tempo balances between allegro and andante, with Rivers’ triple tonguing complemented by the tubist’s portamento effects, finally climax with stretched reed tones and brass grace notes. What elsewhere would be a standard drum solo in pseudo-march tempo actually serves as an introduction to a piano interlude, expressed with contrasting dynamics and varied tempos. Piano patterning squirms forward until speedy rips from Daley change the narrative course. Playing with the swift facility of a valve trombonist, Daley bounces from treble sheets of sound to guttural scoops. Holland’s subsequent strums and ascending string plucks make way for an Arcadian but tough duet between Daley’s tuba puffs and Rivers’ flute peeps. Except for forays into screech mode, the remainder of the flute section opens the narrative to out-and-out swing. Holland’s cello plucks and Barker’s concise small cymbal pings confirm the motion. Kept from any suggestion of prettiness however, the concluding tremolo flute flutters are in sync with Daley’s tuba burbles as rhythmic groove and sound exploration are simultaneously affirmed.

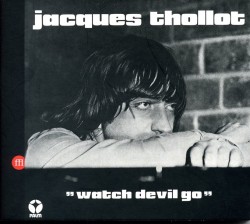

Iconoclastic French drummer Jacques Thollot (1946-2014), a mainstay of the jazz/improv scene, always searched for new forms and styles. That’s what makes some of the 16 (!) tracks on Watch Devil Go (Souffle Continu Records FFL071 soufflecontinurecords.com) fascinating. Together with tenor saxophonist/flutist François Jeanneau and bassist Jean-François Jenny-Clark, the drummer and sometime pianist create free-wheeling and unique energy music on several of these 1974/1975 tracks. Yet Thollot and Jeanneau also play synthesizers. Those forays into wave form shudders can’t seen to decide whether they should be used to add rhythmic impetus with electronic algorithms or mix Baroque-like washes as New Age ambient music. A complete outlier, the title tune adds synthesizer and string quartet vibrations to a simple vocal from Charline Scott that touches more on California folk rock than free jazz. In Extenso and La Dynastie des Wittelsbach are standouts for cutting-edge improv, with Jeanneau’s saxophone piling vibrating scoops and split-tone smears into his solos as Jenny-Clark’s constant pumps and Thollot’s vigorous paradiddles and cymbal clashes move the tempo ever faster, but without loss of control. As for the electronica-oriented tracks, the memorable ones are those like Entre Java et Tombok where the synthesizer’s orchestral qualities are put to use creating multiple sound layers in tandem with the flute’s lowest pitches. With the machines able to replicate many timbres, some of the other notable tracks emphasize the meld of ethereal reed tones and powerful riffs that could swell from an embedded church pump organ. Eleven even sets up a call-and-response between the two synths.

Iconoclastic French drummer Jacques Thollot (1946-2014), a mainstay of the jazz/improv scene, always searched for new forms and styles. That’s what makes some of the 16 (!) tracks on Watch Devil Go (Souffle Continu Records FFL071 soufflecontinurecords.com) fascinating. Together with tenor saxophonist/flutist François Jeanneau and bassist Jean-François Jenny-Clark, the drummer and sometime pianist create free-wheeling and unique energy music on several of these 1974/1975 tracks. Yet Thollot and Jeanneau also play synthesizers. Those forays into wave form shudders can’t seen to decide whether they should be used to add rhythmic impetus with electronic algorithms or mix Baroque-like washes as New Age ambient music. A complete outlier, the title tune adds synthesizer and string quartet vibrations to a simple vocal from Charline Scott that touches more on California folk rock than free jazz. In Extenso and La Dynastie des Wittelsbach are standouts for cutting-edge improv, with Jeanneau’s saxophone piling vibrating scoops and split-tone smears into his solos as Jenny-Clark’s constant pumps and Thollot’s vigorous paradiddles and cymbal clashes move the tempo ever faster, but without loss of control. As for the electronica-oriented tracks, the memorable ones are those like Entre Java et Tombok where the synthesizer’s orchestral qualities are put to use creating multiple sound layers in tandem with the flute’s lowest pitches. With the machines able to replicate many timbres, some of the other notable tracks emphasize the meld of ethereal reed tones and powerful riffs that could swell from an embedded church pump organ. Eleven even sets up a call-and-response between the two synths.

The value of these sessions is that they fill gaps in the history of experiments that created free-flowing contemporary sounds.