Freed from the tyranny of section accompaniment, solo string concertos have long been a feature of notated music. A similar liberation for violins and violas happened years ago in improvised music. However it’s only during the past few years that use of these four-string instruments have been treated as more than a novelty. Sessions such as these, which feature a violin or viola as part of different ensembles, show how the prototypical instrument of so-called classical music is forging an equally impressive role creating freer sounds.

Probably the answer to the question, “when is a string quartet not a string quartet?” is illustrated on SETT’s First and Second (New Wave of Jazz nwoj033 newwaveofjazz.com) during two extended improvisations. Consisting of one linchpin of the traditional string ensemble, the viola, played by the UK’s Benedict Taylor, the disc stretches the chamber music staple’s role by including a double bass, played by Briton John Edwards, and breaks the mould by adding the two acoustic guitars of England’s Daniel Thompson and Belgium’s Dirk Serries. Mercurial and harsh without being coarse, and fluid without depending on an expected groove, both polyphonic tracks contain numerous sequences of both calm and agitation. As viola and bass move through spiccato sweeps and ratcheting pressure, it’s often dual guitar strums which steady the pace and shepherd squeaks, slaps and shakes from all the players into crescendos of jagged glissandi and, later on, speedy intersection. Second SETT is more assured than the First as the collective guitar licks, plus swelling plucks from the bass, set up a clanking backdrop upon which Taylor’s stridently pitched strokes ascend to spectacular flanges. By midpoint, buzzing arco pushes and taut guitar finger picking define a communicative theme. With Edwards’ plucks creating an ambulating ostinato, the narrative stays constant to the end, while allowing for a series of stressed variations from the violist and some below-the-bridge plinks from the guitarists that almost strip strings of their coating. As spiccato sweeps rub against muted glissandi, SETT defines a form that is both exploratory and connected.

Probably the answer to the question, “when is a string quartet not a string quartet?” is illustrated on SETT’s First and Second (New Wave of Jazz nwoj033 newwaveofjazz.com) during two extended improvisations. Consisting of one linchpin of the traditional string ensemble, the viola, played by the UK’s Benedict Taylor, the disc stretches the chamber music staple’s role by including a double bass, played by Briton John Edwards, and breaks the mould by adding the two acoustic guitars of England’s Daniel Thompson and Belgium’s Dirk Serries. Mercurial and harsh without being coarse, and fluid without depending on an expected groove, both polyphonic tracks contain numerous sequences of both calm and agitation. As viola and bass move through spiccato sweeps and ratcheting pressure, it’s often dual guitar strums which steady the pace and shepherd squeaks, slaps and shakes from all the players into crescendos of jagged glissandi and, later on, speedy intersection. Second SETT is more assured than the First as the collective guitar licks, plus swelling plucks from the bass, set up a clanking backdrop upon which Taylor’s stridently pitched strokes ascend to spectacular flanges. By midpoint, buzzing arco pushes and taut guitar finger picking define a communicative theme. With Edwards’ plucks creating an ambulating ostinato, the narrative stays constant to the end, while allowing for a series of stressed variations from the violist and some below-the-bridge plinks from the guitarists that almost strip strings of their coating. As spiccato sweeps rub against muted glissandi, SETT defines a form that is both exploratory and connected.

Berlin-based pianist/synthesizer player Elias Stemeseder and drummer Max Andrzejewski create a more standard ensemble to show off their original compositions on light/tied (WhyPlayJazz WP J 054 whyplayjazz.de). During the program nine pieces are interpreted by the two leaders’ sometimes intensely percussive playing; clarion or deeper-pitched smears from Joris Rühl’s clarinets; creamy Paul Desmond-like lines from alto saxophonist Christian Weidner; moistly decorative, but at times bordering on dissonant, shimmers by violinist Biliana Voutchkova and cellist Lucy Railton; plus additional programmed electronic whizzes. Furthermore, Stemeseder and Andrzejewski provide the rhythmic undercurrent; and churning wave form electronics undermine the string players’ more formalist impulses. The result is discordant at points, but without being off-putting. Paced by brief interludes of expansive string plucks and bass clarinet lowing, the compositions are gentle and melodic, as well as atmospheric. The best instances of how the admixture works are illustrated on Stemeseder’s Tied Light 1 and Andrzejewski’s Héritage. The first works its way from a tinkling piano and trilling clarinet duet to turn harsher, as thinner clarinet runs meet percussive slaps from the piano and drum beats contrast with alto saxophone calm. Until the end, the timbres vibrate between irregular and expressive without losing the thematic thread or slackening the pace. Sunnier, Héritage finds proper string swells intersecting with crackling electronics. as Rühl’s moderated clarinet defines the slightly off-centre exposition while string plucks vibrate sympathetically. Finally, a dramatic finale is constructed out of swift piano chording, sprightly vibrations from both reeds and stabbing string motions.

Berlin-based pianist/synthesizer player Elias Stemeseder and drummer Max Andrzejewski create a more standard ensemble to show off their original compositions on light/tied (WhyPlayJazz WP J 054 whyplayjazz.de). During the program nine pieces are interpreted by the two leaders’ sometimes intensely percussive playing; clarion or deeper-pitched smears from Joris Rühl’s clarinets; creamy Paul Desmond-like lines from alto saxophonist Christian Weidner; moistly decorative, but at times bordering on dissonant, shimmers by violinist Biliana Voutchkova and cellist Lucy Railton; plus additional programmed electronic whizzes. Furthermore, Stemeseder and Andrzejewski provide the rhythmic undercurrent; and churning wave form electronics undermine the string players’ more formalist impulses. The result is discordant at points, but without being off-putting. Paced by brief interludes of expansive string plucks and bass clarinet lowing, the compositions are gentle and melodic, as well as atmospheric. The best instances of how the admixture works are illustrated on Stemeseder’s Tied Light 1 and Andrzejewski’s Héritage. The first works its way from a tinkling piano and trilling clarinet duet to turn harsher, as thinner clarinet runs meet percussive slaps from the piano and drum beats contrast with alto saxophone calm. Until the end, the timbres vibrate between irregular and expressive without losing the thematic thread or slackening the pace. Sunnier, Héritage finds proper string swells intersecting with crackling electronics. as Rühl’s moderated clarinet defines the slightly off-centre exposition while string plucks vibrate sympathetically. Finally, a dramatic finale is constructed out of swift piano chording, sprightly vibrations from both reeds and stabbing string motions.

Adapting the textures of a violin – or viola – so that it plays with equal prominence as other instruments in a small group is the preoccupation of other improvisers. Instances of this are expressed by Swiss violinist Laura Schuler’s quartet; French guitarist Pierrick Hardy’s quartet, featuring violinist Regis Huby; and the trio of American Jason Kao Hwang, who plays both viola and violin. Proclaimed an Acoustic Quartet perhaps because no electric instruments or drums are present, Hardy’s L’Ogre Intact (Émouvance emv 1041 tchamitchian.fr) includes bassist Claude Tchamitchian and clarinettist/basset horn player Catherine Delaunay. A hint of the fusion that informs Hardy’s compositions comes from clarinettist Delaunay’s other instrument. Throughout the disc the quartet aims for relaxed, pastoral interpretations that flow rather than upset. Yet between double bass thumps and acoustic guitar strums, a rhythmic groove is maintained. Flottements is the most realized instance of this traditional/innovative approach. Blending the basset horn’s muted tone with violin mid-pitches and a buzzing double bass continuum, an antique-styled introduction is attained, but it’s soon replaced with a contrapuntal melody from the fiddle that’s lively and dance-like. As the theme swells with spiccato squeaks from Huby, coupled with thin frails from Hardy, Tchamitchian confirms its contemporary relevance with a repeated rhythmic motif. Playing clarinet on the other tracks, Delaunay adds to the warm elaboration of the mostly largo narratives. Concerned with synthesis not confrontation, supple solos are worked into the warm-blooded adaptations. With his violin output usually caressing romantic themes, only rarely, as on Avant dire/Tamasaburö, does Huby demonstrate his command of multi-string coordination and swift triple stopping. Hardy’s skills are more prominent, with an approximation of folk-blues picking on La Violence du terrain; he moves past positioned strums to propel relaxed swing on the final La Fresque with tougher mettle via spectacularly chunky, rhythm guitar licks.

Adapting the textures of a violin – or viola – so that it plays with equal prominence as other instruments in a small group is the preoccupation of other improvisers. Instances of this are expressed by Swiss violinist Laura Schuler’s quartet; French guitarist Pierrick Hardy’s quartet, featuring violinist Regis Huby; and the trio of American Jason Kao Hwang, who plays both viola and violin. Proclaimed an Acoustic Quartet perhaps because no electric instruments or drums are present, Hardy’s L’Ogre Intact (Émouvance emv 1041 tchamitchian.fr) includes bassist Claude Tchamitchian and clarinettist/basset horn player Catherine Delaunay. A hint of the fusion that informs Hardy’s compositions comes from clarinettist Delaunay’s other instrument. Throughout the disc the quartet aims for relaxed, pastoral interpretations that flow rather than upset. Yet between double bass thumps and acoustic guitar strums, a rhythmic groove is maintained. Flottements is the most realized instance of this traditional/innovative approach. Blending the basset horn’s muted tone with violin mid-pitches and a buzzing double bass continuum, an antique-styled introduction is attained, but it’s soon replaced with a contrapuntal melody from the fiddle that’s lively and dance-like. As the theme swells with spiccato squeaks from Huby, coupled with thin frails from Hardy, Tchamitchian confirms its contemporary relevance with a repeated rhythmic motif. Playing clarinet on the other tracks, Delaunay adds to the warm elaboration of the mostly largo narratives. Concerned with synthesis not confrontation, supple solos are worked into the warm-blooded adaptations. With his violin output usually caressing romantic themes, only rarely, as on Avant dire/Tamasaburö, does Huby demonstrate his command of multi-string coordination and swift triple stopping. Hardy’s skills are more prominent, with an approximation of folk-blues picking on La Violence du terrain; he moves past positioned strums to propel relaxed swing on the final La Fresque with tougher mettle via spectacularly chunky, rhythm guitar licks.

If Huby’s violin and the Acoustic Quartet include echoes of the 18th century, then Schuler’s quartet music is strictly 21st. The other members of the group are German tenor saxophonist Philipp Gropper, and fellow Swiss, drummer Lionel Friedli and Hanspeter Pfammatter playing synthesizers. Besides Schuller’s ability to move swiftly from formalist to semi-hoedown to pure improv and on to near fusion in her playing, the contemporary resonance on Metamorphosis (Veto-Records 020 veto-records.ch) centres on Pfammatter’s instrument, whose sonic permutations allow it to replicate the sounds of an acoustic piano, an organ, an electric guitar and even an accordion. Especially on more groove-oriented tracks such as Dancing in the Stratosphere, Friedli projects a popping backbeat which glues together various sound shards from the others; although elsewhere, his nerve beats and patterning help confirm other tunes’ jittery but relaxed melodies. Capable of romantic interludes or strident squeaks if needed, Gropper’s usual role is to serve as a foil for Schuller’s string elaborations. With ghostly synthesizer washes behind, they meld ribald squeaks on his part and banjo-like pizzicato clanks from her on the title tune; or with Pfammatter’s church organ-like chording on Broken Lines, harmonize barbed reed tremolos and rugged string strokes. Z, the CD’s wrap-up, projects variations of these tone permutations, with the outpouring compassing instances of sound unity and severance from all four. As drum ruffs and synthesizer pushes make the narrative more intense and heavier, positioned col legno stabs from the violinist lead to a measured and ambulatory last section and finale.

If Huby’s violin and the Acoustic Quartet include echoes of the 18th century, then Schuler’s quartet music is strictly 21st. The other members of the group are German tenor saxophonist Philipp Gropper, and fellow Swiss, drummer Lionel Friedli and Hanspeter Pfammatter playing synthesizers. Besides Schuller’s ability to move swiftly from formalist to semi-hoedown to pure improv and on to near fusion in her playing, the contemporary resonance on Metamorphosis (Veto-Records 020 veto-records.ch) centres on Pfammatter’s instrument, whose sonic permutations allow it to replicate the sounds of an acoustic piano, an organ, an electric guitar and even an accordion. Especially on more groove-oriented tracks such as Dancing in the Stratosphere, Friedli projects a popping backbeat which glues together various sound shards from the others; although elsewhere, his nerve beats and patterning help confirm other tunes’ jittery but relaxed melodies. Capable of romantic interludes or strident squeaks if needed, Gropper’s usual role is to serve as a foil for Schuller’s string elaborations. With ghostly synthesizer washes behind, they meld ribald squeaks on his part and banjo-like pizzicato clanks from her on the title tune; or with Pfammatter’s church organ-like chording on Broken Lines, harmonize barbed reed tremolos and rugged string strokes. Z, the CD’s wrap-up, projects variations of these tone permutations, with the outpouring compassing instances of sound unity and severance from all four. As drum ruffs and synthesizer pushes make the narrative more intense and heavier, positioned col legno stabs from the violinist lead to a measured and ambulatory last section and finale.

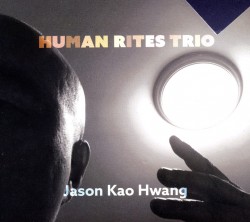

Confirming his allegiance to intense improvising Hwang uses his violin and viola as doubling lead voices in the role soprano and tenor saxophones or trumpet and flugelhorn would take elsewhere. Luckily he and his associates on Human Rites Trio (True Sound Recordings TS03 jasonkaohwang.com), bassist Ken Filiano and drummer Andrew Drury, are perfectly matched, having worked in this configuration for years. Taking a far different approach to the viola than SETT’s Benedict Taylor, Hwang plays it almost exclusively pizzicato, treating it like a four-string mandolin. Most spectacularly, on the foot-tapping Conscious Concave Concrete he manipulates the instrument so at various junctures it takes on sitar and guitar-like affiliations as well as mandolin twangs. Without disrupting his low tones, Filiano also achieves guitar-like facility with fluid solos. Incorporating Drury’s cymbal clashes and steel drum-like suggestions, the trio achieves a singular sound which touches on the blues, as well as international inflections. Playing violin, as on Battle for the Indelible Truth, Hwang’s stretches and multiple stops are as pressurized and extended as the other two’s intense rhythm. Moving into an andante swing section, he backs Filiano’s Slam Stewart-like simultaneous bowing and vocal humming with high pitched trills; but later he creates a pseudo-violin concerto adding a romantic tinge to the tune’s dynamic unrolling. Still, the most dramatic display of the trio’s in-the-moment affiliation is heard on the two-part Words Asleep Spoken Awake. Setting the scene on Part 1, the three create an ambulatory introduction that is rounded and mellifluous until propelled to double in speed by drum rim shots and spiccato violin strokes. This leads to a repetitive multi-string motif that defines Part 2. As the violinist triple stops his strings at prestissimo tempo, Drury’s martial beats and striking pumps from Filiano prevent the narrative from breaking apart while maintaining intensity. Climactically altering his lines by loosening and tightening strings while strumming complementary tones, Hwang supplely and spectacularly demonstrates his skill with a final section where string splays bring up reed or brass intimations as the musical thoughts expressed at the CD’s beginning track are completed.

Confirming his allegiance to intense improvising Hwang uses his violin and viola as doubling lead voices in the role soprano and tenor saxophones or trumpet and flugelhorn would take elsewhere. Luckily he and his associates on Human Rites Trio (True Sound Recordings TS03 jasonkaohwang.com), bassist Ken Filiano and drummer Andrew Drury, are perfectly matched, having worked in this configuration for years. Taking a far different approach to the viola than SETT’s Benedict Taylor, Hwang plays it almost exclusively pizzicato, treating it like a four-string mandolin. Most spectacularly, on the foot-tapping Conscious Concave Concrete he manipulates the instrument so at various junctures it takes on sitar and guitar-like affiliations as well as mandolin twangs. Without disrupting his low tones, Filiano also achieves guitar-like facility with fluid solos. Incorporating Drury’s cymbal clashes and steel drum-like suggestions, the trio achieves a singular sound which touches on the blues, as well as international inflections. Playing violin, as on Battle for the Indelible Truth, Hwang’s stretches and multiple stops are as pressurized and extended as the other two’s intense rhythm. Moving into an andante swing section, he backs Filiano’s Slam Stewart-like simultaneous bowing and vocal humming with high pitched trills; but later he creates a pseudo-violin concerto adding a romantic tinge to the tune’s dynamic unrolling. Still, the most dramatic display of the trio’s in-the-moment affiliation is heard on the two-part Words Asleep Spoken Awake. Setting the scene on Part 1, the three create an ambulatory introduction that is rounded and mellifluous until propelled to double in speed by drum rim shots and spiccato violin strokes. This leads to a repetitive multi-string motif that defines Part 2. As the violinist triple stops his strings at prestissimo tempo, Drury’s martial beats and striking pumps from Filiano prevent the narrative from breaking apart while maintaining intensity. Climactically altering his lines by loosening and tightening strings while strumming complementary tones, Hwang supplely and spectacularly demonstrates his skill with a final section where string splays bring up reed or brass intimations as the musical thoughts expressed at the CD’s beginning track are completed.

It’s clear that the variety of ways violins and violas can be integrated into improvised music are as individual as the person playing therm. These discs confirm this truism.