I first heard Ian Tamblyn’s (Once Was A) Village, sung by our publisher David Perlman in my backyard one lovely summer day several years ago. He had learned the song after hearing it performed in Kensington Market by the SPECIAL INTEREST group. The Spark (independent KBG1905 thespecialinterestgroup.bandcamp.com/album/the-spark) is the debut CD by this self proclaimed “cultural/political project dedicated to playing music with a progressive message and providing a playlist for labour and activist groups.” Originally published digitally during the pandemic, it has now been released in physical form. The disc begins with that same Tamblyn song celebrating the small-town aspects of communities within large cities, with some added lyrics by Rebecca Campbell. As in most of the group’s repertoire the song is combined with another to make an effective medley, in this case Pat Metheny and Lyle Mays’ (Cross the) Heartland.

I first heard Ian Tamblyn’s (Once Was A) Village, sung by our publisher David Perlman in my backyard one lovely summer day several years ago. He had learned the song after hearing it performed in Kensington Market by the SPECIAL INTEREST group. The Spark (independent KBG1905 thespecialinterestgroup.bandcamp.com/album/the-spark) is the debut CD by this self proclaimed “cultural/political project dedicated to playing music with a progressive message and providing a playlist for labour and activist groups.” Originally published digitally during the pandemic, it has now been released in physical form. The disc begins with that same Tamblyn song celebrating the small-town aspects of communities within large cities, with some added lyrics by Rebecca Campbell. As in most of the group’s repertoire the song is combined with another to make an effective medley, in this case Pat Metheny and Lyle Mays’ (Cross the) Heartland.

The quintet is comprised of Campbell (lead and backing vocals, guitar and percussion), Kevin Barrett (various acoustic and electric guitars, mandolin, loops, lead and backing vocals), Jim Bish (various saxophones and flutes, backing vocals), Ian de Sousa (bass, loops) and Rakesh Tewari (drums and percussion). They are supplemented by the nine-voice People’s Chorus on two of my favourite tracks, Willie P. Bennett’s (Who’s Gonna Get The) Last Word (In) and Ed McCurdy’s classic Last Night I Had The Strangest Dream, here interpolated with John Lennon’s Give Peace A Chance. Also of particular note are Mimi Fariña and James Oppenheim’s Bread and Roses, Steven Stills’ For What It’s Worth, with Harris Seaton’s Peace, Love and Understanding, and a brilliant interlacing of Bruce Cockburn’s If I Had A Rocket Launcher and Talking Heads’ Listening Wind where Campbell’s voice, channeling David Byrne, is eerily reminiscent of both Laurie Anderson and Kate Bush. That track also includes an excerpt from Elijah Harper’s historic address to Parliament demanding that Indigenous voices be included in any changes to the Canadian Constitution.

I also must mention the title track, Campbell’s own The Spark, an anthem of sorts that proclaims, “the spark, ignites the flame, that sheds a light, on all we once held true.” This disc is a heady throwback to the protest era of the sixties and early seventies, while addressing contemporary concerns, and with a great backbeat to get you up on your feet.

Anne Lindsay tells us in the notes to Soloworks 2 (annelindsay.bandcamp.com/album/soloworks-2-2), “This record is dedicated to St. Anne’s Anglican Church in Toronto where it was recorded in November 2021 during the global pandemic. St. Anne’s was built in 1907 and contained a Byzantine dome with spectacular acoustics. Murals by the Group of Seven and sculptures by Frances Loring and Florence Wyle were added in the 1920s. Sadly in June 2024 the church suffered a devastating fire and all that remains of this historic Canadian cultural gem are parts of the exterior walls. I am grateful to share a record of this outstanding acoustic space with you.”

Anne Lindsay tells us in the notes to Soloworks 2 (annelindsay.bandcamp.com/album/soloworks-2-2), “This record is dedicated to St. Anne’s Anglican Church in Toronto where it was recorded in November 2021 during the global pandemic. St. Anne’s was built in 1907 and contained a Byzantine dome with spectacular acoustics. Murals by the Group of Seven and sculptures by Frances Loring and Florence Wyle were added in the 1920s. Sadly in June 2024 the church suffered a devastating fire and all that remains of this historic Canadian cultural gem are parts of the exterior walls. I am grateful to share a record of this outstanding acoustic space with you.”

Lindsay’s violin (or is it a fiddle?), nyckelharpa (a “keyed” and bowed hurdy-gurdy-like instrument from Sweden) and voice fill this wondrous space with joyous and contemplative reverberant sounds. The music is lyrical and mostly folk-based, at times rhythmic as in the Celtic-sounding Carolina Parakeet where the jig-like fiddle is accompanied by the hand drumming of Mark Mariash. Fitting for the venue, several of Lindsay’s compositions – did I mention they are all originals? – are religious expressions, including the opening Votum Mane (morning vow or promise), Credo, The Lord’s Prayer and Benedictus which is introduced by the sound of the church’s bells. Others are inspired by water: Down by the Noisy River, Headwaters Ramble and The Sea and the Sky. Throughout we are treated to a thoughtful and melodious journey, with Lindsay the buoyant and entertaining guide.

It is great to have this testament as a reminder of what a precious space we lost with the demise of St. Anne’s. It continues to serve the community, holding services in the Parish Hall on Dufferin at Dundas. From its website I take the following: “We are grateful for your continued support to our church community following the devastating loss of our historic church. Help us rebuild our ministry and create a church that reflects our faith through contemporary Canadian art and through ministry to all people. You can contribute directly to us by visiting our Canada Helps page. We are most in need of support for our general fund, which helps us with our day-to-day operations.” A truly worthy cause.

I’m a sucker for the Doppler effect, so I was immediately captivated by the title work of The White Birds, a new release from the Latvian Music Information Centre featuring String Trio Baltia (SKANI 171 lmic.lv/en/skani/catalogue?id=254). Composed by Gundega Šmite, the birds in question are mute swans, collared doves, seagulls and white storks. I was a bit surprised to realize that the siren-like opening movement depicted “mute” creatures. Also, that Baltic seagulls are quite subdued compared to local denizens of our lakefront, although they do have that same characteristic glissando cry. In between, the doves coo and peck as might be expected and in the finale the storks mostly scratch and tap rhythmically, with no discernible song.

I’m a sucker for the Doppler effect, so I was immediately captivated by the title work of The White Birds, a new release from the Latvian Music Information Centre featuring String Trio Baltia (SKANI 171 lmic.lv/en/skani/catalogue?id=254). Composed by Gundega Šmite, the birds in question are mute swans, collared doves, seagulls and white storks. I was a bit surprised to realize that the siren-like opening movement depicted “mute” creatures. Also, that Baltic seagulls are quite subdued compared to local denizens of our lakefront, although they do have that same characteristic glissando cry. In between, the doves coo and peck as might be expected and in the finale the storks mostly scratch and tap rhythmically, with no discernible song.

The real reason I was drawn to the CD is the inclusion of Latvian-born Canadian composer Tālivaldis Ķeniņš’ (1919-2008) Trio for violin, viola and cello written in 1989. That’s the same year that he visited Latvia for the first time since fleeing the country during the later days of the Second World War. At that time he returned to Paris where he had been a student before the outbreak of the war, and after completing studies (with Messiaen and Tony Aubin, among others) he emigrated to Canada in 1951. Ķeniņš was active as an organist, administrator for the Canadian League of Composers and as lecturer and professor at the Faculty of Music, U of T, retiring Emeritus in 1984. He was one of Canada’s most prolific composers, whose orchestral output included eight numbered symphonies, and more than a dozen concertante works, as well as myriad solo vocal, choral, chamber and keyboard pieces.

Although commissioned by the Toronto Latvian Concert Association and the Ontario Arts Council almost half a century ago, like so much of Ķeniņš’ output, the trio has remained unrecorded until now. The three-movement work is lyrical and occasionally dark, beginning with a Moderato con moto where the “motor” sounds are like footsteps. Adagietto teneroso is sparse, with a mournful violin melody over simple lower string chords, which grows into counterpoint between the three players. The final Vivo e marcato starts playfully enough, with each of the instruments in turn leading a game of tag. This gives way to a sombre middle section before returning to the chase, and after another contemplative pause ends in a flurry of activity. Although the trio receives a thoroughly professional performance here, I think the work is straightforward enough to be tackled by accomplished amateur performers and I may use it as inspiration to return to my own cello, which has been mostly languishing in its case since the COVID lockdowns.

The disc also includes Castillo interior by Latvian Pēteris Vasks, a tribute to Saint Teresa of Avila originally for violin and cello and revised for string trio in 2021. In it, quiet quasi-medieval melodies alternate with rhythmic passages representing the seven courtyards through which the soul must pass to enter “the castle,” a journey that requires “prayer, perseverance, self-knowledge and awareness of sin.” This is followed by the Gran duo funebre for viola and cello by Gundaris Pone who says, “My intention was not to write mourning music but to show how Latvians regard this big, final question […] approaching the issue of death with a sunnier outlook.” I think the references to Shostakovich perhaps belie this sunny outlook, but nevertheless it is a compelling work.

Cello recordings seem to have been in constant rotation on my stereo (yes, I’m a dinosaur) for the past couple of months, with some repertoire new to me, and a couple of old favourites as well. Perhaps the most unusual, or at least the most unfamiliar to my ears, is the latest from South African cellist, singer and composer Abel Selaocoe. Hymns of Bantu (Warner Classics warnerclassics.com/release/hymns-bantu) is an intriguing blend of African popular idioms and western art music. Selaocoe is front and centre, with his virtuosic cello playing and powerful vocalizing, in arrangements of his compositions by Fred Thomas ranging from small ensembles to near orchestral forces with the participation of the Ensemble Manchester Collective. Even the small groups sound large, with rhythmic, percussion-heavy textures dominating the accompaniments.

Cello recordings seem to have been in constant rotation on my stereo (yes, I’m a dinosaur) for the past couple of months, with some repertoire new to me, and a couple of old favourites as well. Perhaps the most unusual, or at least the most unfamiliar to my ears, is the latest from South African cellist, singer and composer Abel Selaocoe. Hymns of Bantu (Warner Classics warnerclassics.com/release/hymns-bantu) is an intriguing blend of African popular idioms and western art music. Selaocoe is front and centre, with his virtuosic cello playing and powerful vocalizing, in arrangements of his compositions by Fred Thomas ranging from small ensembles to near orchestral forces with the participation of the Ensemble Manchester Collective. Even the small groups sound large, with rhythmic, percussion-heavy textures dominating the accompaniments.

Mixed in amongst the mostly upbeat original tunes are two classics of the cello repertoire which appear mid-disc – the Sarabande from Bach’s Suite for Unaccompanied Cello No.6 arranged for cello and small string ensemble, and an Improvisation on Marin Marais’ Les voix humaines entitled Voices of Bantu featuring Selaocoe’s hymn-like vocal lines over contemplative solo cello. The mood then returns to flamboyance with Takamba, a moto perpetuo featuring cello, electric bass, African percussion, viola and Ensemble Manchester. Two movements from contemporary Italian cellist/composer Giovanni Sollima’s L.B. Files return us to a quasi-classical realm before we find ourselves back in Selaocoe’s growling vocal/percussion-based expanded pop sensibility in the rousing closer Camagu. For someone like me whose exposure to South African idioms comes largely from Paul Simon’s work with Ladysmith Black Mambazo, this album is really ear-opening, and just as energizing.

French composer Fernande Decruck (1896-1954) is one of many accomplished women to be “discovered” lately, brought to light through our expanding understanding of the shortcomings of the historically male-centric perception of classical music. Concertante Works Volume 2 (Claves 50-3108 claves.ch/fr/collections/all-albums/products/fernande-decruck-concertante-works-vol-2) features Decruck’s Concerto for Cello and Orchestra; Les Trionons: Suite for Harpsichord (or Piano) and Orchestra; Sonata in C-sharp for Alto Saxophone (or Viola) and Orchestra; and The Bells of Vienna: Suite of Waltzes, with the Jackson Symphony Orchestra under Matthew Aubin. The soloist in the cello concerto (1932) is Jeremy Crosmer and he is in fine form in this dramatic, late-Romantic tour de force. It’s in the usual three movement form, although the first is marked Andantino non troppo rather than the allegro we might expect, with the cello featured in rapid rising lines against the calmer orchestra. This is followed by an Adagietto, Molto Tranquillo with the cello in gentle singing melodies above the peaceful orchestration. A vigorous Allegro Energico with virtuosic cello interpolations brings this satisfying work to a close.

French composer Fernande Decruck (1896-1954) is one of many accomplished women to be “discovered” lately, brought to light through our expanding understanding of the shortcomings of the historically male-centric perception of classical music. Concertante Works Volume 2 (Claves 50-3108 claves.ch/fr/collections/all-albums/products/fernande-decruck-concertante-works-vol-2) features Decruck’s Concerto for Cello and Orchestra; Les Trionons: Suite for Harpsichord (or Piano) and Orchestra; Sonata in C-sharp for Alto Saxophone (or Viola) and Orchestra; and The Bells of Vienna: Suite of Waltzes, with the Jackson Symphony Orchestra under Matthew Aubin. The soloist in the cello concerto (1932) is Jeremy Crosmer and he is in fine form in this dramatic, late-Romantic tour de force. It’s in the usual three movement form, although the first is marked Andantino non troppo rather than the allegro we might expect, with the cello featured in rapid rising lines against the calmer orchestra. This is followed by an Adagietto, Molto Tranquillo with the cello in gentle singing melodies above the peaceful orchestration. A vigorous Allegro Energico with virtuosic cello interpolations brings this satisfying work to a close.

The saxophone concerto (1943) appears here in the viola version featuring Mitsuru Kubo. The viola spends most of the four-movement work in the three and a half octave range that it shares with the cello, so a casual listener might mistake this for another concerto for the tenor of the violin family, but nevertheless it is an important addition to the viola’s repertoire. Les Trionons (1946) is a playful work here presented in the version for harpsichord, featuring Mahan Esfanhani. It has a bit of a “Les Six” feel to it. The disc ends with the charming, bright and lively waltz suite. It’s an early example of the use of vibraphone in an orchestral context, an indication of the innovative nature of this too little-known composer.

Mieczysław Weinberg is another composer who has risen from relative obscurity in recent years. Born in Warsaw in 1919, he escaped to Minsk after the Nazis invaded Poland and spent the rest of his life in the Soviet Union where he was befriended and encouraged by Dmitri Shostakovich. There have been so many recordings of his music in the past decade that it is hard to imagine that he was virtually ignored in the years leading up to his death in 1996. Weinberg Complete Music for Cello and Orchestra (NAXOS 8.574679 naxos.com/CatalogueDetail/?id=8.574679) includes a Concertino from 1948 for cello and string orchestra, never performed during the composer’s lifetime, a Fantasia for cello and orchestra completed in 1953, and a reworking and expansion of the concertino into the Concerto for Cello and Orchestra, Op.43 (1948/56). Soloist Nikolay Shugaev is featured with the Siberian Tyumen Philharmonic Orchestra under the direction of Yuri Medianik in striking performances of all three works.

Mieczysław Weinberg is another composer who has risen from relative obscurity in recent years. Born in Warsaw in 1919, he escaped to Minsk after the Nazis invaded Poland and spent the rest of his life in the Soviet Union where he was befriended and encouraged by Dmitri Shostakovich. There have been so many recordings of his music in the past decade that it is hard to imagine that he was virtually ignored in the years leading up to his death in 1996. Weinberg Complete Music for Cello and Orchestra (NAXOS 8.574679 naxos.com/CatalogueDetail/?id=8.574679) includes a Concertino from 1948 for cello and string orchestra, never performed during the composer’s lifetime, a Fantasia for cello and orchestra completed in 1953, and a reworking and expansion of the concertino into the Concerto for Cello and Orchestra, Op.43 (1948/56). Soloist Nikolay Shugaev is featured with the Siberian Tyumen Philharmonic Orchestra under the direction of Yuri Medianik in striking performances of all three works.

It is particularly interesting to hear the difference between the concertino and concerto, the latter being roughly twice the length of its predecessor. Of special note is the development of the Yiddish themes in the scherzo-like second movement, the extended cadenza of the third movement and quasi-military bombast, and echoes of Shostakovich, in the finale of the concerto. Shugaev gives a lyrical and at times muscular performance somewhat reminiscent of Mstislav Rostropovich, who premiered the concerto in 1957. The centrepiece of the recording is the Fantasia Op.52, which, in the words of NAXOS’ annotator Richard Whitehouse, “is among the most appealing of Weinberg’s earlier works in the way it channels elements of the concerto format into a span as formally symmetrical as it is expressively spontaneous.” Performances and production values are faultless on this welcome release.

One of the greatest thrills of my life was having the opportunity to meet Yo-Yo Ma while I was an extra in the episode directed by Atom Egoyan of Ma’s Inspired by Bach series of collaborative videos based on Bach’s Cello Suites. The day began in the green room where Ma introduced himself to all the extras, asking a little something about each of us, information which he remembered and returned to at the end of the day when we all gathered again. I was charmed. Not only that, but on the lunch break he allowed a number of the cello students among us to play his million-dollar instrument; a chance in a lifetime for many of those young musicians!

One of the greatest thrills of my life was having the opportunity to meet Yo-Yo Ma while I was an extra in the episode directed by Atom Egoyan of Ma’s Inspired by Bach series of collaborative videos based on Bach’s Cello Suites. The day began in the green room where Ma introduced himself to all the extras, asking a little something about each of us, information which he remembered and returned to at the end of the day when we all gathered again. I was charmed. Not only that, but on the lunch break he allowed a number of the cello students among us to play his million-dollar instrument; a chance in a lifetime for many of those young musicians!

A related thrill was receiving the Deutsche Grammophon recording Shostakovich – The Cello Concertos featuring Yo-Yo Ma with the Boston Symphony Orchestra under Andris Nelsons (deutschegrammophon.com/en/catalogue/products/shostakovich-cello-concertos-yo-yo-ma-andris-nelsons-13798). The Concerto No.1 in E-flat Major, Op.107 ranks among my all-time favourites and I have in my vinyl collection both the first recording of it with its dedicatee Rostropovich and Eugene Ormandy’s Philadelphia Orchestra from 1960 and Ma’s 1983 performance with the same forces. This new recording, with its state-of-the-art technology, surpasses both of those in sound quality and dynamic range, and Ma, 40 years on, shows a maturity and an understanding of Shostakovich’s music that is formidable.

I also have Rostropovich’s 1976 recording of the Concerto No.2 in G Major, Op.126 with Seiji Ozawa and the Boston Symphony Orchestra, but I must say that it wasn’t until Ma’s current release with that orchestra that I really got to appreciate the full sonic depth of the piece. We think of the vocal range of basso profundo as being typically Russian, but I’ve come to think that term might just as aptly apply in the percussion section. As well as prominent timpani parts in both concertos, there is a profoundly deep big bass drum featured in duet with the cellist in the first movement cadenza of the second concerto which is amazing. Wow, do my speakers pop! It’s truly visceral, a feeling which continues throughout this marvelous recording.

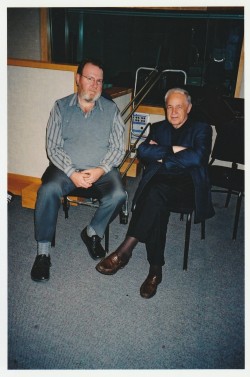

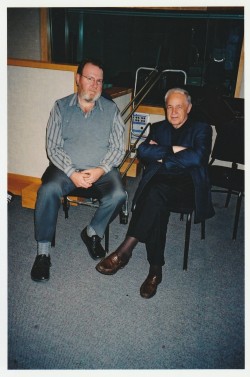

One of the first instances, and still the most prestigious in my career as a music journalist (The WholeNote notwithstanding), was the publication (in French translation) of an article about Pierre Boulez that I wrote for the Université de Montréal’s journal Circuit: Revue Nord-Américaine de Musique du XXe siècle (Volume 3 Number 1, 1992). It was an analysis of a workshop/rehearsal of Mémoriale that Boulez gave at the Royal Conservatory in Toronto during a Canadian tour in conjunction with his residency at Festival Nova Scotia in 1991. The performers were flute soloist Robert Aitken and members of the New Music Concerts (NMC) ensemble who had first performed the work some six weeks earlier under the direction of frequent Boulez collaborator Jean-Pierre Drouet.

One of the first instances, and still the most prestigious in my career as a music journalist (The WholeNote notwithstanding), was the publication (in French translation) of an article about Pierre Boulez that I wrote for the Université de Montréal’s journal Circuit: Revue Nord-Américaine de Musique du XXe siècle (Volume 3 Number 1, 1992). It was an analysis of a workshop/rehearsal of Mémoriale that Boulez gave at the Royal Conservatory in Toronto during a Canadian tour in conjunction with his residency at Festival Nova Scotia in 1991. The performers were flute soloist Robert Aitken and members of the New Music Concerts (NMC) ensemble who had first performed the work some six weeks earlier under the direction of frequent Boulez collaborator Jean-Pierre Drouet.

This was almost a decade before my own association with NMC, where I served as general manager from 1999 until 2019. During my tenure there I met many of the world’s most illustrious composers, but the absolute epitome of this was the time I spent as escort to maestro Boulez when he became the laureate of the Glenn Gould Prize in November 2002. In the concert at Glenn Gould Studio mounted to honour the recipient of the prestigious prize, Christina Petrowska-Quilico performed Piano Sonata No.1, Fujiko Imajishi was featured in Anthèmes for solo violin, and Aitken and the NMC musicians reprised their performance of Mémoriale. Other works on the programme included Messagesquisse (with Boulez’s protégé Jean-Guihen Queyras as cello soloist), Éclats, Dérive and Pli selon pli (featuring Patricia Green). Boulez attended the final day of rehearsals, and although he was only scheduled to conduct one piece on the programme, he evidently felt that sufficient preparatory work had been done by Aitken in the preceding week and he decided to conduct the entire concert. It was a truly memorable performance and a career highlight for many of the musicians.

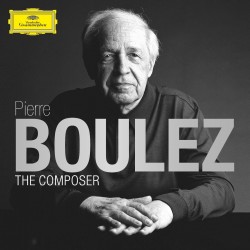

Well, that was a rather lengthy introduction to set up my final review for the issue. Boulez lived from 1925 until 2016 and to mark the centenary of his birth Deutsche Grammophon has released Pierre Boulez: The Composer (deutschegrammophon.com/en/catalogue/products/pierre-boulez-the-composer-9905). It’s a commemorative box set including 11 CDs of recordings hand-picked by Boulez representing virtually all of his output spanning more than half a century. There is also a disc of historic recordings of Le Marteau sans maître, Le Soleil des eaux (second version 1950) and a 1956 performance of Sonatine for flute and piano featuring Severino Gazzelloni and David Tudor, along with an hour-long conversation between the set’s producer Claude Samuel and Boulez recorded at IRCAM in 2011. The interview is in French, but there is a complete translation in the 252-page booklet that also includes an homage by Laurent Bayle, an introduction by Samuel, detailed bilingual programme notes (including some provided by Boulez himself), texts of the poetry Boulez set to music and photographs. It’s a very impressive and informative package.

Well, that was a rather lengthy introduction to set up my final review for the issue. Boulez lived from 1925 until 2016 and to mark the centenary of his birth Deutsche Grammophon has released Pierre Boulez: The Composer (deutschegrammophon.com/en/catalogue/products/pierre-boulez-the-composer-9905). It’s a commemorative box set including 11 CDs of recordings hand-picked by Boulez representing virtually all of his output spanning more than half a century. There is also a disc of historic recordings of Le Marteau sans maître, Le Soleil des eaux (second version 1950) and a 1956 performance of Sonatine for flute and piano featuring Severino Gazzelloni and David Tudor, along with an hour-long conversation between the set’s producer Claude Samuel and Boulez recorded at IRCAM in 2011. The interview is in French, but there is a complete translation in the 252-page booklet that also includes an homage by Laurent Bayle, an introduction by Samuel, detailed bilingual programme notes (including some provided by Boulez himself), texts of the poetry Boulez set to music and photographs. It’s a very impressive and informative package.

Boulez, who came to prominence shortly after the Second World War along with Stockhausen, Xenakis and a host of other seminal composers of the avant-garde, was a complex and sometimes cantankerous individual. After initially bonding with such senior composers as Messiaen (with whom he studied) and René Leibowitz, he turned on his former mentors with contempt, eschewing all that came before including the likes of Stravinsky and Schoenberg (see his essay Schoenberg is Dead).

Boulez took Schoenberg’s 12-tone principle that no note should be repeated until all the other 11 semitones had appeared, and applied this to the other parameters of music such as rhythm, duration, attack and dynamics. In later years, as he blossomed into a world-renowned conductor, not only of the music of his contemporaries but also of earlier periods particularly in the realm of opera, in his own compositions he relaxed his strictures somewhat.

This collection, containing virtually all the music Boulez acknowledged and even a few pieces he had not previously allowed to be performed, is presented in more or less chronological order, although this is complicated by the fact that he almost never stopped revising his works. It begins with the craggy pieces of the “angry young man,” Douze notations for piano, Sonatine, the three piano sonatas, Livre pour quatuor and Structures Livre 1 for two pianos.

While most of the recordings date from the 1990s there are numerous exceptions, including the abovementioned Structures featuring Alfons and Aloys Kontarsky recorded in 1960, Rituel in memoriam Bruno Maderna from a 1982 Sony recording, the 1989 “definitive” version – a rare designation by Boulez – of Pli selon pli from 2002 and sur incises with Boulez conducting soloists of l’Ensemble intercontemporain (EI) in 2012. Virtually all of the ensemble pieces are conducted by Boulez, most performed by EI, but some featuring larger groups including the BBC Symphony, the Vienna Philharmonic and Ensemble Modern Orchestra. One exception is Domaines for clarinet and instrumental groups. The soloist is Michel Portal with Musique vivante under Diego Masson in a recording from 1971. Portal also performs the solo version of Domaines. There are also two versions of Anthèmes; the solo version is performed by violinist Jeanne-Marie Conquer and the version with electronics, realized at Boulez’s IRCAM facility at the Centre Pompidou, features Hae-Sun Kang. As in the Toronto performance I mentioned earlier, Jean-Guihen Queyras is the soloist in a 2000 performance of Messagesquisse, sur le nom de Paul Sacher.

I have missed some important works in this list but make no mistake they are all contained in this fabulous centenary tribute to one of the most significant figures of our time, a musical genius with whom I am privileged to have spent a memorable weekend.

We invite submissions. CDs and DVDs should be sent to: DISCoveries, The WholeNote c/o Music Alive, The Centre for Social Innovation, 720 Bathurst St. Toronto ON M5S 2R4. Comments and digital releases are welcome at discoveries@thewholenote.com.

A recent case in point is Alice Ping Yee Ho – Dark Tales, the latest from Duo Concertante (Navona Records navonarecords.com/catalog/nv6748), an evocative five-movement work inspired by Tom Dawe’s story collection An Old Man’s Winter Night. Each movement channels a ghost story rooted in Newfoundland folklore. The Newfoundland-based duo of violinist Nancy Dahn and pianist Timothy Steeves who commissioned the work is in top form here, giving each movement a distinctive colour.

A recent case in point is Alice Ping Yee Ho – Dark Tales, the latest from Duo Concertante (Navona Records navonarecords.com/catalog/nv6748), an evocative five-movement work inspired by Tom Dawe’s story collection An Old Man’s Winter Night. Each movement channels a ghost story rooted in Newfoundland folklore. The Newfoundland-based duo of violinist Nancy Dahn and pianist Timothy Steeves who commissioned the work is in top form here, giving each movement a distinctive colour.  Although not eerie in the same way, Five Scenes for Orchestra by Azores- and New York City-based Canadian composer Nathan Henninger (rich records nathanhenninger.com/music) is equally dramatic. The recording features the Scoring Berlin Orchestra, session musicians drawn from Berlin’s most prestigious orchestras, with conducting duties shared by the composer and Bernhard Wünsch. Although we are not given clues to a specific story line from the movement titles – Misterioso, Maestoso, Brightly, Misterioso and Gently – if you close your eyes you can likely invent a scenario to go with the lushly orchestrated sounds.

Although not eerie in the same way, Five Scenes for Orchestra by Azores- and New York City-based Canadian composer Nathan Henninger (rich records nathanhenninger.com/music) is equally dramatic. The recording features the Scoring Berlin Orchestra, session musicians drawn from Berlin’s most prestigious orchestras, with conducting duties shared by the composer and Bernhard Wünsch. Although we are not given clues to a specific story line from the movement titles – Misterioso, Maestoso, Brightly, Misterioso and Gently – if you close your eyes you can likely invent a scenario to go with the lushly orchestrated sounds.  Another debut recording, Shades of Mouring, features Israeli-born, New York City-based cellist and composer Tamar Sagiv (Sono Luminus SLE-70041 sonoluminus.com/sonoluminus/shades-of-mourning). In the notes Sagiv says “I am writing these words while the Middle East, my place of birth, is bleeding. Like me, my friends, family, and neighbours who live on the other side of fences built to divide us carry excruciating pain that flows deep as the wars continue.”

Another debut recording, Shades of Mouring, features Israeli-born, New York City-based cellist and composer Tamar Sagiv (Sono Luminus SLE-70041 sonoluminus.com/sonoluminus/shades-of-mourning). In the notes Sagiv says “I am writing these words while the Middle East, my place of birth, is bleeding. Like me, my friends, family, and neighbours who live on the other side of fences built to divide us carry excruciating pain that flows deep as the wars continue.”  There are some minimalist aspects to David Occhipinti’s Camera Lucida (elastic records davidocchipinti.bandcamp.com/album/camera-lucida-elastic-recordings), a collection of chamber works that brings to my mind the music of the late Michael J. Baker, longtime artistic director of Toronto’s Arraymusic ensemble. The Camera Ensemble comprises some fine Toronto jazz players – Occhipinti on guitar, Michael Davidson, vibes and marimba, Dan Fortin contrabass, Aline Homzy violin and Virginia MacDonald clarinet – with special guests from the classical world on selected tracks: Max Christie on clarinet and bass clarinet, Fraser Jackson bassoon and Andy Ballantyne piccolo.

There are some minimalist aspects to David Occhipinti’s Camera Lucida (elastic records davidocchipinti.bandcamp.com/album/camera-lucida-elastic-recordings), a collection of chamber works that brings to my mind the music of the late Michael J. Baker, longtime artistic director of Toronto’s Arraymusic ensemble. The Camera Ensemble comprises some fine Toronto jazz players – Occhipinti on guitar, Michael Davidson, vibes and marimba, Dan Fortin contrabass, Aline Homzy violin and Virginia MacDonald clarinet – with special guests from the classical world on selected tracks: Max Christie on clarinet and bass clarinet, Fraser Jackson bassoon and Andy Ballantyne piccolo.  And this just in… As the deadline for filing my column fast approaches I have just received a disc that is inspiring a nostalgic romp down memory lane. Art Decade (Cantaloupe Music contaqtnewmusic.bandcamp.com/album/art-decade) comprising some fabulous music from the time I spent at CKLN-FM in the late ‘80s, is a wonderful revisioning by Evan Ziporan and Toronto’s ContaQt (formerly Contact). Compositions by Robert Fripp, Harold Budd, Brian Eno and David Bowie are featured in stunning arrangements by Ziporan and/or ContaQt founder Jerry Pergolesi.

And this just in… As the deadline for filing my column fast approaches I have just received a disc that is inspiring a nostalgic romp down memory lane. Art Decade (Cantaloupe Music contaqtnewmusic.bandcamp.com/album/art-decade) comprising some fabulous music from the time I spent at CKLN-FM in the late ‘80s, is a wonderful revisioning by Evan Ziporan and Toronto’s ContaQt (formerly Contact). Compositions by Robert Fripp, Harold Budd, Brian Eno and David Bowie are featured in stunning arrangements by Ziporan and/or ContaQt founder Jerry Pergolesi.