Ratamacue! is one of the exclamations that the percussionist is called upon to ejaculate during Chanter la pomme (to flirt/to seduce) for snare drum. This is the first of eight short pedagogical exercises in the collection Pommes by Robert Lemay recently recorded by Ryan Scott and released by the Canadian Music Centre’s digital arm Centretracks (CMCCT 11218 musiccentre.ca/node/154883). The digital EP is the result of an ongoing collaboration between the Sudbury-based composer and one of Toronto’s leading percussion soloists. Pommes is a series of études for solo percussion instruments, four for snare drum, one for temple blocks, one for toms, one for tam-tam and one for bass drum. The title refers to the percussion sound POM, but also to the apple (the fruit). Each piece has a title that includes the word “apple” in French (pomme). Only the exuberant first includes vocalizations by the performer, but all require dexterity, precision and control. One might wonder whether a solo percussionist using just one (non-pitched) instrument for each exercise could sustain interest over the cumulative duration of roughly 20 minutes. I’m pleased to say that it is indeed possible, and in fact the result is quite entertaining. Of particular note are the delicacy of Tomber dans les pommes (to pass out) for temple blocks, the deep gong’s resonance of Pomme d’Adam (Adam’s apple) for tam-tam and the intensity of La grosse pomme (The Big Apple) for bass drum, which juxtaposes the low rumble and “pomming” of the skin of the drum with rhythmic patterns of rim shots. All in all, an exuberant adventure leading me to believe, as I have always suspected, that being a drummer must be a lot of fun!

Ratamacue! is one of the exclamations that the percussionist is called upon to ejaculate during Chanter la pomme (to flirt/to seduce) for snare drum. This is the first of eight short pedagogical exercises in the collection Pommes by Robert Lemay recently recorded by Ryan Scott and released by the Canadian Music Centre’s digital arm Centretracks (CMCCT 11218 musiccentre.ca/node/154883). The digital EP is the result of an ongoing collaboration between the Sudbury-based composer and one of Toronto’s leading percussion soloists. Pommes is a series of études for solo percussion instruments, four for snare drum, one for temple blocks, one for toms, one for tam-tam and one for bass drum. The title refers to the percussion sound POM, but also to the apple (the fruit). Each piece has a title that includes the word “apple” in French (pomme). Only the exuberant first includes vocalizations by the performer, but all require dexterity, precision and control. One might wonder whether a solo percussionist using just one (non-pitched) instrument for each exercise could sustain interest over the cumulative duration of roughly 20 minutes. I’m pleased to say that it is indeed possible, and in fact the result is quite entertaining. Of particular note are the delicacy of Tomber dans les pommes (to pass out) for temple blocks, the deep gong’s resonance of Pomme d’Adam (Adam’s apple) for tam-tam and the intensity of La grosse pomme (The Big Apple) for bass drum, which juxtaposes the low rumble and “pomming” of the skin of the drum with rhythmic patterns of rim shots. All in all, an exuberant adventure leading me to believe, as I have always suspected, that being a drummer must be a lot of fun!

Sticking with a theme, John Psathas – Percussion Project Vol.1 (navonarecords.com/catalog/nv6204) is the culmination of another composer/percussionist collaboration that began in 2013 when Omar Carmenates arranged Psathas’ piano and gamelan piece Waiting: Still for percussion trio. Psathas is a Greek-New Zealand composer and in the past five years a number of his chamber works have been arranged for percussion ensemble by Carmenates, an American, who directs this project and is the featured soloist in a number of the works. There are 10 members of the nameless percussion ensemble involved throughout the disc, so there is no question of monophony in this instance – just about every sound imaginable from a percussion instrument turns up somewhere on the disc. But a few of the pieces employ fewer, similar instruments such as Musica scored for two players, Carmenates on vibraphone and a different partner on marimba in each of the three movements: Soledad, Chia and El Dorado.

Sticking with a theme, John Psathas – Percussion Project Vol.1 (navonarecords.com/catalog/nv6204) is the culmination of another composer/percussionist collaboration that began in 2013 when Omar Carmenates arranged Psathas’ piano and gamelan piece Waiting: Still for percussion trio. Psathas is a Greek-New Zealand composer and in the past five years a number of his chamber works have been arranged for percussion ensemble by Carmenates, an American, who directs this project and is the featured soloist in a number of the works. There are 10 members of the nameless percussion ensemble involved throughout the disc, so there is no question of monophony in this instance – just about every sound imaginable from a percussion instrument turns up somewhere on the disc. But a few of the pieces employ fewer, similar instruments such as Musica scored for two players, Carmenates on vibraphone and a different partner on marimba in each of the three movements: Soledad, Chia and El Dorado.

The disc begins with the full ensemble work Corybas which started out in life as a traditional piano trio. It opens with a gentle ostinato of mallet instruments overlaid by a lovely vibraphone melody. This eventually gives way to a raucous section where unpitched instruments come to the fore before gradually subsiding into a calm finale with low marimba notes, bowed vibraphone drones and a high chiming melody. The second work, Piano Quintet, also began as a piece for the standard formation named in its title, but in this instance the piano (played by Daniel Koppelman) is retained in the transcription, and the strings are replaced by percussion instruments. Again there is a wealth of ostinati, but not in the minimalist sense of strict repetition with minor variations. The work is multilayered in the extreme with different voices rising out of the murky textures, often to beautiful effect. Drum Dances, commissioned by Dame Evelyn Glennie for drum kit and piano, features Justin Alexander in the starring role, with the piano accompaniment here transcribed for mallet instruments and a variety of other pitched and non-pitched beaters. Psathas says he was “greatly inspired by the drumming of Dave Weckl, the very different piano styles of Keith Jarrett and Chick Corea, and the enormous energy in the music of guitarists like Steve Vai.” There is great energy and great beauty in these dances, and all throughout this disc.

John Psathas: Percussion Project is a good reminder that the modern percussion arsenal is vast and varied, and that although studies may begin with intriguing exercises like those devised by Robert Lemay as mentioned above, this merely scratches the surface of a wild and wonderful world that can include anything that can be struck, bowed or beaten, sometimes including the kitchen sink.

A good example of this will be seen at New Music Concerts’ April 28 presentation “Luminaries,” a tribute to two masters of 20th-century composition who passed away in recent years, Pierre Boulez and Gilles Tremblay. Ryan Scott will be one of three percussionists involved in the concert along with Rick Sacks and David Schotzko. Both Boulez’s Le Marteau sans maître (with mezzo Patricia Green) and Tremblay’s piano concerto Envoi (with soloist Louise Bessette) are scored for three percussionists, although in very different ways. In the Boulez, one player is assigned the rare xylorimba throughout (Scott), another vibraphone (Sacks), and only the third (Schotzko) plays on a variety of instruments from the percussionist’s “kitchen.” In the Tremblay all three have extensive set-ups. It should be quite a sight.

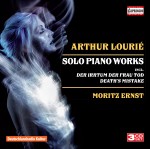

And speaking of New Music Concerts as I am wont to do – I’ve been general manager there for the past 20 years – I am writing this the morning after a stunning performance at Gallery 345 by young German pianist Moritz Ernst. The evening was NMC’s annual benefit concert, in this instance a recital that included music of Sandeep Bhagwati (who was in attendance and gave an insightful introduction to his complex work Music of Crossings with examples provided by the pianist), Karlheinz Stockhausen, Michael Edward Edgerton (a piece written for Ernst), Miklós Maros and Arthur Lourié.

And speaking of New Music Concerts as I am wont to do – I’ve been general manager there for the past 20 years – I am writing this the morning after a stunning performance at Gallery 345 by young German pianist Moritz Ernst. The evening was NMC’s annual benefit concert, in this instance a recital that included music of Sandeep Bhagwati (who was in attendance and gave an insightful introduction to his complex work Music of Crossings with examples provided by the pianist), Karlheinz Stockhausen, Michael Edward Edgerton (a piece written for Ernst), Miklós Maros and Arthur Lourié.

In 2016 Ernst’s recording of the complete Solo Piano Works of Arthur Lourié was released by Capriccio (3CDs C5281 naxos.com/catalogue/item.asp?item_code=C5281). Lourié played an important role in the earliest stages of the organization of Soviet music after the 1917 Revolution but later went into exile, failing to return from an official visit to Berlin in 1921. His works were thereafter banned in the USSR. His music reflects his close connections with contemporary writers and artists associated with the Futurist movement. In 1922 he settled in Paris where he maintained a close relationship with Igor Stravinsky, and then fled to the USA in 1940 when the Germans occupied the city. He settled in New York and wrote some film scores but gained almost no performances for his more serious works.

Lourié wrote extensively for the piano, as these three discs attest, but although he lived until 1966, in the last 25 years of his life after fleeing Europe he did not compose any solo keyboard works. The collection includes his early Soviet period (in which his interests included Futurism, somewhat experimental forms, micro- and expanded- tonality, and even some work with 12-tone techniques, albeit not in the Schoenbergian manner) and the output of his two decades-long residency in France. Despite the long association with Stravinsky, Lourié’s piano writing does not involve the percussive aspects so prominent in that of his countryman. It is much more subdued and gentle, tinged by the Impressionist sensibilities so prominent in his adopted land. Nocturne, the work that Ernst performed here in Toronto, with its quiet left-hand clusters gradually building and then receding under the right-hand musings, is a prime example. Written in 1928, it is one of the last solo pieces Lourié would compose. Two short final solo works complete his piano oeuvre, the little Berceuse de la chevrette (1936) and the Phoenix Park Nocturne (1938), “to the memory of James Joyce.”

An exception to the chronological order of the first two CDs, the third disc of the set concludes with a 1917 setting of an “absurdes dramolette” for piano and speaker entitled Der Irrtum der Frau Tod (Death’s Mistake), a half-hour-long monodrama by Velimir Chlébnikov. For this dramatic recitation Ernst is joined by Oskar Ansull. Although narrated in German, there is a full translation in the accompanying booklet. Ansull is also featured on CD2 in the peculiar Nash Marsh (Our March) from 1918 which is a strangely lilting “march” in 3 / 4 time.

This collection is an important addition to the discography, and to the awareness of an innovative and once-influential composer whose legacy virtually disappeared after falling out of favour with the Soviet regime. Congratulations to Moritz Ernst for embracing lesser-known repertoire. His discography also includes music of Walter Braunfels, Viktor Ullmann, Norbert von Hannenheim and Sir Malcolm Arnold. Also Joseph Haydn! As Ernst explains in an interview with composer Moritz Eggert in the notes for Volume One of a projected 11CD edition of the complete solo piano works of Haydn (Perfect Noise PN 1701), the keyboard music of Haydn remains surprisingly under-recorded with the exception of a very few sonatas.

Thanks also to Ernst for gracing a very appreciative audience at Gallery 345 with his insights and extraordinary skill.

We invite submissions. CDs and comments should be sent to: DISCoveries, WholeNote Media Inc., The Centre for Social Innovation, 503 – 720 Bathurst St. Toronto ON M5S 2R4.

David Olds, DISCoveries Editor

discoveries@thewholenote.com