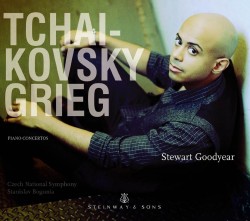

Tchaikovsky; Grieg – Piano Concertos - Stewart Goodyear; Czech National Symphony; Stanislav Bogunia

Tchaikovsky; Grieg – Piano Concertos

Tchaikovsky; Grieg – Piano Concertos

Stewart Goodyear; Czech National Symphony; Stanislav Bogunia

Steinway & Sons Records 30035

These performances of the warhorses by Tchaikovsky and Grieg are on fire. There is an energy and passion from both the remarkable Stewart Goodyear and the incredible Czech National Symphony that makes this a must-listen-to CD for pianists. Goodyear speaks of the collaboration as “dancing” and the performances certainly weave long musical lines and pulsating shapes like dance choreography. I like the tempos in the Tchaikovsky concerto. Both pianist and orchestra refrained from romantic over-indulgence and kept the music flowing in grand, sweeping gestures. This concerto often suffers from affectations and egocentric playing. Goodyear’s impressive technique was used with integrity to interpret the music. He coaxed beautiful tone poems and colours from the piano. He embraced the lush harmonic worlds of Tchaikovsky and made the rhythms dance in balletic forms. His incisive articulation and trills that border on the phenomenal will keep listeners on the edge of their seats. The second movement sparkles effervescently at a quick tempo but the slower sections are tender and carefully nuanced. The concerto ends in a blaze of virtuosic display and fireworks from both piano and orchestra.

The Grieg concerto was impeccable. It sang in lyric colours and the ensemble between pianist and orchestra was exemplary. The tempos and timings breathed and evolved freely while creating naturally flowing phrases. The lyrical and sensitive second movement sang with luminous tone and expressiveness. The third movement was crisp and performed with scintillating precision.

It is so refreshing to hear these often over-done concertos played with such love, mastery and musical integrity. Bravo to Stewart Goodyear and the Czech National Symphony, as well as to Steinway for this excellent CD.