Canada’s Jasper Wood has long been one of my favourite violinists, ever since he used to come into the music store where I was working some ten years ago to promote his terrific CDs of the Eckhardt-Gramatté and Gary Kulesha solo Caprices and Saint-Saëns’ Music for Violin and Piano. Since then he has built a wide-ranging discography, including CDs of music by Ives, Stravinsky, Bartók and Morawetz. His latest CD on the American Max Frank Music label (MFM 003) is titled Chartreuse, and features Wood and his long-time accompanist David Riley in beautifully judged performances of sonatas by Mozart, Debussy and Richard Strauss.

Canada’s Jasper Wood has long been one of my favourite violinists, ever since he used to come into the music store where I was working some ten years ago to promote his terrific CDs of the Eckhardt-Gramatté and Gary Kulesha solo Caprices and Saint-Saëns’ Music for Violin and Piano. Since then he has built a wide-ranging discography, including CDs of music by Ives, Stravinsky, Bartók and Morawetz. His latest CD on the American Max Frank Music label (MFM 003) is titled Chartreuse, and features Wood and his long-time accompanist David Riley in beautifully judged performances of sonatas by Mozart, Debussy and Richard Strauss.

The Mozart is the Sonata in B-Flat Major K454, and the playing here — as it is throughout the CD — is Wood at his usual best: clean; accurate; tasteful; sweet-toned; stylish; intelligent and thoughtful. The Debussy sonata is given an impassioned reading; and in the Strauss Sonata in E-Flat Major, Op.18 Wood and Riley handle the virtuosic demands with sensitive subtlety, invoking Brahms rather than providing a mere display of fireworks. The sound throughout is resonant and warm, and the instrumental balance just right. The CD digipak comes without booklet notes, but none are really necessary; listening to this CD is like being at a memorable live recital.

Cellist Simon Fryer teams up with pianist Leslie De’Ath on a fascinating CD of Victorian Cello Sonatas on the independent American label Centaur Records (CRC 3216). The composers Algernon Ashton and Samuel Liddle are probably new to you — they certainly were to me — but they are representative of that generation of late 19th century English composers whose style went out of fashion in the years before the Great War, and whose works virtually disappeared from the repertoire. Not surprisingly, their works here — Ashton’s Sonata No.2 in G Major from 1882 and Liddle’s Sonata in E-Flat Major and his Elegy from 1889 and 1900 respectively — are world premiere recordings; the Sonata No.2 in D Minor, Op.39 by Sir Charles Villiers Stanford completes the recital.

Cellist Simon Fryer teams up with pianist Leslie De’Ath on a fascinating CD of Victorian Cello Sonatas on the independent American label Centaur Records (CRC 3216). The composers Algernon Ashton and Samuel Liddle are probably new to you — they certainly were to me — but they are representative of that generation of late 19th century English composers whose style went out of fashion in the years before the Great War, and whose works virtually disappeared from the repertoire. Not surprisingly, their works here — Ashton’s Sonata No.2 in G Major from 1882 and Liddle’s Sonata in E-Flat Major and his Elegy from 1889 and 1900 respectively — are world premiere recordings; the Sonata No.2 in D Minor, Op.39 by Sir Charles Villiers Stanford completes the recital.

The previously unknown Liddle sonata was discovered by De’Ath in the course of his hobby of collecting musical documents and ephemera. The predominant influence seems to be German, especially the music of Mendelssohn and Brahms, but that’s hardly surprising, given the musical connections between the two countries in Victorian times. Ashton’s music, although scarcely acknowledged at home, was widely published in Germany, where he had studied at the Leipzig Conservatory; Liddle and Stanford also studied in Leipzig during the late 1870s, as had Arthur Sullivan some 20 years earlier.

While the Stanford sonata may be the stronger work, there is a great deal of worthwhile and highly attractive music here, clearly the work of competent and imaginative craftsmen. Fryer and De’Ath certainly present a persuasive case for the pieces, surmounting the often formidable technical challenges with expansive playing that never resorts to overly Romantic indulgence. Fryer’s tone in the lower register is particularly lovely.

Sometimes, admittedly, works do remain buried or neglected for good reasons, but CDs like this one remind us just how rewarding it can be to take the path less trodden.

Fans of violinist Christian Tetzlaff will be delighted with his new CD of three Mozart Sonatas for Piano and Violin, with Lars Vogt at the keyboard (Ondine ODE 1204-2). The sonatas are those in B Flat Major K454, G Major K379 and A Major K526 and Tetzlaff more than lives up to his usual world-class standard in works that require not only virtuosity but also a great deal of sensitivity. His playing seems effortless, with a smooth legato and a lovely range of dynamics.

Fans of violinist Christian Tetzlaff will be delighted with his new CD of three Mozart Sonatas for Piano and Violin, with Lars Vogt at the keyboard (Ondine ODE 1204-2). The sonatas are those in B Flat Major K454, G Major K379 and A Major K526 and Tetzlaff more than lives up to his usual world-class standard in works that require not only virtuosity but also a great deal of sensitivity. His playing seems effortless, with a smooth legato and a lovely range of dynamics.

The booklet notes tell us that Vogt and Tetzlaff are both very conscious of the ambiguity created in these sonatas by Mozart’s customary emotional range, and their performances quite beautifully reflect this. Tetzlaff apparently came to Mozart’s music fairly late — well, at 15; late for a prodigy — but clearly understands that growing older is crucial to understanding the music.

The sound is spacious without being overly resonant, with the two instruments clearly separated but nicely balanced, reminding us — as does the CD’s title — that these were not originally written as sonatas for solo violin with piano accompaniment.

There are another two outstanding string quartet releases from the Naxos label. Hindemith String Quartets Vol.2 (8.572164) features the final three quartets of the composer’s cycle of seven, in impeccable performances by the Amar Quartet. The Zurich-based ensemble was granted use of the name of Hindemith’s own 1920s string quartet by the Hindemith Institute in 1995 on the centenary of the composer’s birth, so their interpretations here are clearly authoritative. Quartet No.5 is from 1923; Quartets Nos.6 and 7 are from 1943 and 1945, when Hindemith had settled in America. They’re terrific works, demonstrating his mastery of string writing and reminding one yet again that the opinion – still held in some quarters – that Hindemith was a dry and cerebral composer is patently false. Volume 1, featuring Quartets 2 and 3, is available on Naxos 8.572163; hopefully a third volume with Quartets 1 and 4 will soon complete an outstanding set.

There are another two outstanding string quartet releases from the Naxos label. Hindemith String Quartets Vol.2 (8.572164) features the final three quartets of the composer’s cycle of seven, in impeccable performances by the Amar Quartet. The Zurich-based ensemble was granted use of the name of Hindemith’s own 1920s string quartet by the Hindemith Institute in 1995 on the centenary of the composer’s birth, so their interpretations here are clearly authoritative. Quartet No.5 is from 1923; Quartets Nos.6 and 7 are from 1943 and 1945, when Hindemith had settled in America. They’re terrific works, demonstrating his mastery of string writing and reminding one yet again that the opinion – still held in some quarters – that Hindemith was a dry and cerebral composer is patently false. Volume 1, featuring Quartets 2 and 3, is available on Naxos 8.572163; hopefully a third volume with Quartets 1 and 4 will soon complete an outstanding set.

The New Zealand String Quartet are the performers on the CD Asian Music for String Quartet (8.572488), a quite fascinating – and often quite beautiful – example of contemporary musical East meets West. There are single works by China’s Zhou Long and Gao Ping, Cambodia’s Chinary Ung (now an American citizen), Japan’s Toru Takemitsu and Tan Dun, the Chinese composer now resident in New York City. Titles like Song of the Ch’in (a Chinese plucked string instrument) and Bright Light and Cloud Shadows are a good indication of the sort of music you can expect here. It’s all superbly played by the New Zealand quartet. The recording was made in the acoustically superb St. Anne’s Church in west end Toronto, with the ever-reliable Norbert Kraft as recording engineer.

The New Zealand String Quartet are the performers on the CD Asian Music for String Quartet (8.572488), a quite fascinating – and often quite beautiful – example of contemporary musical East meets West. There are single works by China’s Zhou Long and Gao Ping, Cambodia’s Chinary Ung (now an American citizen), Japan’s Toru Takemitsu and Tan Dun, the Chinese composer now resident in New York City. Titles like Song of the Ch’in (a Chinese plucked string instrument) and Bright Light and Cloud Shadows are a good indication of the sort of music you can expect here. It’s all superbly played by the New Zealand quartet. The recording was made in the acoustically superb St. Anne’s Church in west end Toronto, with the ever-reliable Norbert Kraft as recording engineer.

It’s always nice to open a CD when you have absolutely no idea – or, at least, very little – what to expect. I must admit to never having heard of the Polish composer and conductor Ignaz Waghalter (1881-1949), who moved to Berlin at the age of 17 and finally ended up, like so many others, in the United States after fleeing the Nazi regime in the late 1930s. Waghalter was born seven years after Schoenberg, the same year as Bartok, only one year before Stravinsky, two years before Anton Webern and four years before Alban Berg, but never showed any interest in what could be termed avant-garde music, a fact which certainly contributed to his virtual anonymity after the Second World War. His music, always strongly melodic, looks back to the world of Schumann, Brahms and Bruch, and never forward to the world of atonality and innovation. Naxos has issued a quite revelationary CD of his Violin Music (8572809), featuring the Greek-Polish violinist Irmina Trynkos in her debut CD and the first in her Waghalter Project, created specifically to promote the music of this composer.

It’s always nice to open a CD when you have absolutely no idea – or, at least, very little – what to expect. I must admit to never having heard of the Polish composer and conductor Ignaz Waghalter (1881-1949), who moved to Berlin at the age of 17 and finally ended up, like so many others, in the United States after fleeing the Nazi regime in the late 1930s. Waghalter was born seven years after Schoenberg, the same year as Bartok, only one year before Stravinsky, two years before Anton Webern and four years before Alban Berg, but never showed any interest in what could be termed avant-garde music, a fact which certainly contributed to his virtual anonymity after the Second World War. His music, always strongly melodic, looks back to the world of Schumann, Brahms and Bruch, and never forward to the world of atonality and innovation. Naxos has issued a quite revelationary CD of his Violin Music (8572809), featuring the Greek-Polish violinist Irmina Trynkos in her debut CD and the first in her Waghalter Project, created specifically to promote the music of this composer.

The main offering here is the Violin Concerto Op.15 from 1911, a beautiful work that recalls Bruch and Brahms from the opening bars without ever showing quite the same sense of depth and scale. The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra under Alexander Walker provides exemplary accompaniment in this and in the Rhapsodie Op.9 from 1906, a shorter work again strongly reminiscent of Brahms; both are world premiere recordings.

Three attractive works for violin and piano complete the disc: the Sonata in F minor Op.5; the Idyll Op.19b; and Geständnis, Trynkos being joined in these by pianist Giorgi Latsabidze.

Trynkos is a relatively new talent on the concert scene, but plays with warmth, style and confidence; she is clearly one to watch.

As for Waghalter, it will be interesting to see what, if any, other examples of his music will now be resurrected. There is certainly a great deal to enjoy here, but it is perhaps not too difficult to come up with an answer to the question posed at the end of the booklet notes: “How was it possible that this music went missing for a century?” To be fair though, that’s a question that can be asked about a good number of early 20th century European composers – especially Jewish ones – who fell victim to the political changes in the inter-war years and to the rejection after the Second World War of anything that was redolent of the old German musical tradition.

The excellent Swiss violinist Rachel Kolly D’Alba is back with her latest CD, American Serenade (Warner Classics 2564 65765-7), accompanied by the Orchestre National des Pays de la Loire under John Axelrod. In her booklet notes, D’Alba comments on the lack of boundaries between the multitude of different styles in American music. Certainly all three composers represented here were, as she notes, continually dogged by the question of whether their music was “serious’ or “popular” but for her it simply illustrates the fascinating complexity of American music. The Fantasy on Porgy and Bess opens the CD, George Gershwin’s music appearing in Alexander Courage’s arrangement for violin and orchestra of eight songs from the opera (– or was it a musical?). Leonard Bernstein’s Serenade after Plato’s Symposium is not heard all that often, but the composer apparently considered it his best work. When the conductor here, John Axelrod, was a pupil of Bernstein in the early 1980s it was the first work he studied with the composer, lending this performance a real sense of authority. Franz Waxman’s Carmen Fantasie on themes from Bizet’s opera completes the disc. It’s a darker work than the Sarasate Fantasy on the same opera, and has long been a cult favourite with violinists. D’Alba is in great form throughout a terrific CD.

The excellent Swiss violinist Rachel Kolly D’Alba is back with her latest CD, American Serenade (Warner Classics 2564 65765-7), accompanied by the Orchestre National des Pays de la Loire under John Axelrod. In her booklet notes, D’Alba comments on the lack of boundaries between the multitude of different styles in American music. Certainly all three composers represented here were, as she notes, continually dogged by the question of whether their music was “serious’ or “popular” but for her it simply illustrates the fascinating complexity of American music. The Fantasy on Porgy and Bess opens the CD, George Gershwin’s music appearing in Alexander Courage’s arrangement for violin and orchestra of eight songs from the opera (– or was it a musical?). Leonard Bernstein’s Serenade after Plato’s Symposium is not heard all that often, but the composer apparently considered it his best work. When the conductor here, John Axelrod, was a pupil of Bernstein in the early 1980s it was the first work he studied with the composer, lending this performance a real sense of authority. Franz Waxman’s Carmen Fantasie on themes from Bizet’s opera completes the disc. It’s a darker work than the Sarasate Fantasy on the same opera, and has long been a cult favourite with violinists. D’Alba is in great form throughout a terrific CD.

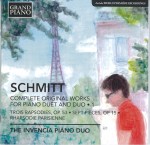

Florent Schmitt – Complete Original Works for Piano Duet and Duo 1

Florent Schmitt – Complete Original Works for Piano Duet and Duo 1