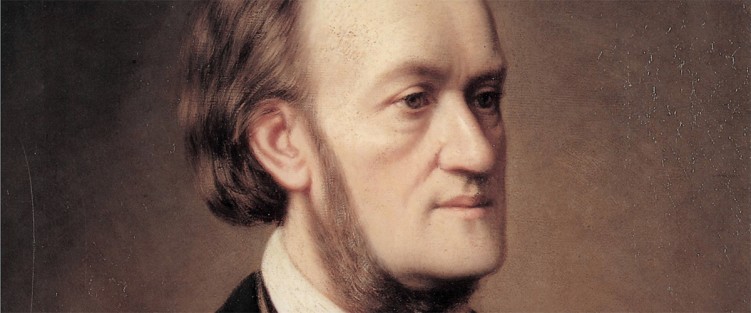

Earlier this fall, the relationship of the music of Wagner and the State of Israel once more leapt back into public prominence, a Valkyrie of controversy once again bellowing its “Hojotoho” to the world.

Earlier this fall, the relationship of the music of Wagner and the State of Israel once more leapt back into public prominence, a Valkyrie of controversy once again bellowing its “Hojotoho” to the world.

An Israeli radio station – the public broadcaster no less – broke the longstanding and hardened, if unofficial, ban on Wagner’s music in that country by presenting the third act of Götterdämmerung to an unsuspecting public at the beginning of September. The station soon apologized, citing the pain that the broadcast might have caused Holocaust survivors. Ironically, the performance in question was a live recording from Bayreuth led by the Jewish Daniel Barenboim, long a Wagner champion.

The apology itself created another firestorm. Although the traditional arguments for banning Wagner in Israel are both Hitler’s affinity for Wagner, and the composer’s own repulsive anti-Semitism, the head of the Wagner Society in Israel, Jonathan Livny, said the ban was a mistake. Livny admitted that although Wagner’s ideology was “terrible,” the music was beautiful, and the “aim was to divide the man from his art.” This, I’m relatively sure, represents the view of many enlightened listeners all over the world, both those who love Wagner and those who hate him. Art and the artist should be separated; the work must be allowed to stand on its own merits. That is what art itself demands.

These days, interestingly, this traditional view (which is not only confined to music, but exists in all the arts) is beginning to come under renewed scrutiny from an unlikely source – the #MeToo movement. Granted, the connection is a tangential one: much of #MeToo, with its wide ambit, has nothing to do with the arts, let alone Wagner, but the movement has, among other things, reminded us that for many, it is perfectly legitimate to refuse to divide the artist from his or her art. Maybe they shouldn’t be divided; maybe artists and their art exist in a complicated, roundabout, mutually self-referencing cycle of meaning. Maybe allowing judgments of the two to intersect is a more sophisticated and honest view of artistic reality. Maybe the old traditional “hate the artist but love the art” is a very superficial attitude towards the power of aesthetic life. Maybe that’s only what you believe when nothing is at stake.

I must say I have more than a little sympathy for this line of reasoning. The notion that music exists in some perfectly insulated temple of pure meaning, untroubled and unconnected to the rest of the turbulent, messy activity of life robs it of its authenticity and credibility, robs it of the opportunity it has to be firmly and powerfully in the world. Music-making is deeply grounded in politics, ideology and social discourse. It always has been. To assume that there is a separate, unsullied aesthetic dimension, in which pure judgments of musical worth can be made, is appealing perhaps, but is simply an ideology that passes as unassailable truth. It’s dangerous, no doubt, and demands from us care and attention and grace, but perhaps it’s time to suggest that art can legitimately be judged on moral as well as aesthetic grounds, including the moral behaviour and actions of its creators.

That might mean one thing when we’re discussing the revival of Louis Riel, another when we look at Madama Butterfly. In Wagner’s case, if we would just be honest with ourselves, we would admit that the personality of the composer, his beliefs and his art have always been inextricably linked. We always let the overwhelming power of the music blind us to a reality we know is lurking in the background. It’s not that we don’t understand the questionable quality of Wagner’s art – it’s just that we decide not to care.

The basic bone caught in the throat of modern Wagnerians has to do with his oft-stated and repugnant anti-Semitism, a virulent anti-Semitism that we are expected to believe infected his life but left his art untainted. But surely just to state that is to play at the edges of the absurd. The Israeli novelist Amos Oz has said that all art in the end is a portrait of the hand holding the pen creating it, and surely he is right. It would be almost inhuman to suggest that an ideology and worldview so central to Wagner’s life and being could be hermetically sealed off from his work. Wagner’s anti-Semitism was not merely a prejudice, an unreasonable hatred of a group of people. It was a world view. Jews to Wagner were the ultimate scapegoat – the root cause of everything corrupted in the German world. Wagner was not just an anti-Semite; he was a primary intellectual progenitor of the Third Reich. To blithely say that Wagner was Hitler’s “favourite” composer, the way you might choose Bedřich Smetana or I might choose Michael Haydn, is to glide over this central point. Wagner was the key to Nazism. “Whoever wants to understand National Socialism,” said Hitler, “must first understand Wagner.” From the horse’s mouth, so to speak.

And, of course, this philosophy is not just central to Wagner’s life; it is at the heart of Wagner’s art as well. In his magnum opus, the Ring, the gnomic and dwarfish Alberich and Mime are surely none other than thinly disguised, dog-whistle portraits of his ultimate Jewish scapegoat, obvious to Wagner’s 19th-century audiences, banging out a dissonant hammered song in the bowels of the tetralogy’s body. It is the curse of Alberich, of the ultimate scapegoat, that haunts the Ring, and, in the end, no one, not Wotan, not Siegfried, not Brünnhilde, can escape it, a curse symbolized by the burning Valhalla. Perhaps if some intrepid director made the flames at the end of Götterdämmerung emanate from a Reichstag fire, or inscribed Arbeit Macht Frei over Mime’s demonic workshop, we would get the point. The Ring is as inherently anti-Semitic as Das Judenthum im der Musik.

So maybe our Israeli friends are not so crazy. As for the rest of us, sitting in the opera house or concert hall, assiduously “dividing the man from his art,” it’s time, perhaps, for us to be neither surprised nor indignant if we find #MeToo-inspired questions disturbing our pleasure.

Robert Harris is a writer and broadcaster on music in all its forms. He is the former classical music critic of the Globe and Mail and the author of the Stratford Lectures and Song of a Nation: The Untold Story of O Canada.