Bright Light, Dark Time

![]()

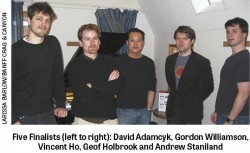

On March 26, 2009, during a live radio broadcast and webcast from the Rolston Recital Hall of the Banff Centre in the Alberta Rockies, the young Canadian composer Andrew Staniland became a double winner. The jury in the CBC/Radio-Canada Evolution competition for young Canadian composers named him the winner of both the National Grand Prize ($20,000) and the Prix de l’Orchestre de la Francophonie Canadienne ($5,000) for his composition Devolution, a work composed during a month-long residency (along with his co-finalist composers, David Adamcyk, Vincent Ho, Geof Holbrook and Gordon Williamson at the Banff Centre). The live audience and the online listeners voted too and, accordingly, the People’s Choice award ($5,000) went to Vincent Ho.

On March 26, 2009, during a live radio broadcast and webcast from the Rolston Recital Hall of the Banff Centre in the Alberta Rockies, the young Canadian composer Andrew Staniland became a double winner. The jury in the CBC/Radio-Canada Evolution competition for young Canadian composers named him the winner of both the National Grand Prize ($20,000) and the Prix de l’Orchestre de la Francophonie Canadienne ($5,000) for his composition Devolution, a work composed during a month-long residency (along with his co-finalist composers, David Adamcyk, Vincent Ho, Geof Holbrook and Gordon Williamson at the Banff Centre). The live audience and the online listeners voted too and, accordingly, the People’s Choice award ($5,000) went to Vincent Ho.

CBC/Radio-Canada’s Evolution Composers Competition was a unique event. It followed in the footsteps of the earlier CBC/Radio-Canada National Radio Competition for Young Composers, which had been the principal means by which the national music departments of both CBC Radio and Radio-Canada (with the collaboration of the Canada Council for the Arts) identified and developed emerging young Canadian composers. I served as English Radio coordinator of that competition, which ran from 1974 to 2003.

It had been a productive investment in talent development; its laureates, collectively, form a Who’s Who of Canadian composers of the present, people such as Denys Bouliane, Brian Current, Chris Paul Harman, Melissa Hui, Kelly Marie Murphy, Michael Oesterle, James Rolfe and Ana Sokolovic. The Grand Prize winner of what turned out to be its final edition, in 2003, was Analia Llugdar.

Following that 2003 competition, when we would have begun planning the next edition of the project, my Radio-Canada co-coordinator and I were advised that a new direction would be required for any future competition. A small group of producers from both CBC and Radio-Canada was formed, and we drafted a number of proposals that addressed several criteria, especially a desire for the inclusion of a much greater new media component. The process of discussing, debating the details of the proposals and persuading all the various authorities in both networks proved to be a very long one. Eventually, the CBC/Radio-Canada Evolution competition launched in 2008.

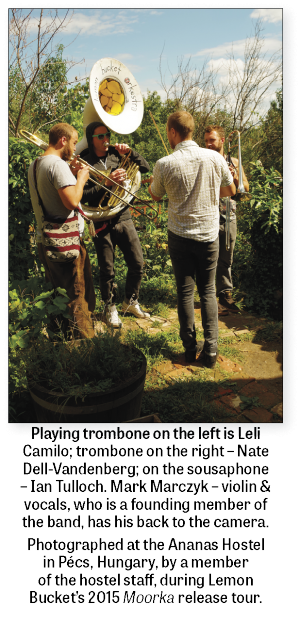

Canadian composers under the age of 35 were invited to submit samples of their work to a pre-selection jury. There were 150 entries, and five composers were selected by the jury as finalists to advance to the second round, which was held at the Banff Centre. Each finalist composer received a $5,000 grant as recognition of their selection.

In March of 2009, the five finalists arrived in Banff and participated in a draw to determine the final details of the orchestration of the competition pieces they would write during their month-long residency. While at Banff, the composers also produced blogs describing the experience of composing competitively. A team of videographers documented the residency. The blogs, videos and other assets were posted online, providing the public a window into the finalists’ experiences as they composed their competition pieces.

The Ensemble contemporaine de Montréal (ECM+) and their artistic director, Véronique Lacroix, were chosen as the performing entity for the final phase of Evolution, due in part to their demonstrated commitment to the mission of encouraging emerging composers. The members of ECM+ arrived in Banff at the end of the composition process, rehearsed the newly composed works and then performed the five compositions in a live broadcast/webcast in the presence of the final-round jury. Andrew Staniland and Vincent Ho prevailed as winners; all five composers gained valuable experience and international visibility, not to mention the performances and broadcasts on both radio networks.

The Evolution competition was praised as a resounding success. The new format, combining both new media and conventional broadcasting, appeared to achieve the goal of encouraging emerging young Canadian composers, while providing audiences unprecedented access to and involvement in the various stages of the competition. In fact, the members of the organizing team, producers Sandy Thacker at CBC, Pascale Labrie at Radio-Canada and I were awarded a CBC President’s Award later in 2009 for our efforts. Unfortunately, major structural and budgetary changes were under way at both CBC and Radio-Canada that gradually reduced their capacity to produce original content; despite efforts to continue and develop the young composers’ competition, it was to be no more.

For the participating young composers, however, the Evolution experience proved to be a watershed moment. Looking back, Andrew Staniland makes the following observations: “In retrospect, 2009 was a turning point for me ... On the positive side, it was a year of winning the National Grand Prize at the CBC's Evolution Composers Competition, and the year I was offered an amazing job at Memorial University, a place I am proud to call home. On the negative side, it was the last year of the CBC Young Composers Program. I was one of the last young composers to enjoy the mentorship and visibility that the CBC had so richly offered to previous generations. While I am grateful for the support I received and the relationships made, I know that composers coming after me will have a harder go of it.

“I remember the final night of the Competition in March 2009. It was a capstone event preceded by a wonderful month surrounded by creativity, amazing colleagues and the natural splendours that Banff is well known for. I was stunned when they called my name as the grand prize winner. Stunned not only for the honour, but by the palpable contrast in the room. Many of the CBC crew working that night were given notice that very evening that their jobs were gone. On the stage, a prize bestowed; in the control room, layoffs and the final dismantling of new music at the CBC. That last CBC young composers competition was a very bright light in a very dark time.”

A dark time indeed. The years between 2007 and 2010 marked the cessation of the various projects that had supported the development of Canadian composers at CBC Radio, including the CBC Radio Orchestra, CBC Radio’s participation in the International Rostrum of Composers, the CBC Records label, CBC commissions, CBC composition competitions and the network contemporary music program Two New Hours. In spite of this, young composers who had enjoyed earlier support from CBC Radio continued to develop and flourish. For example, Andrew Staniland’s requiem for the AIDS pandemic, Dark Star Requiem (words by Jill Battson, commissioned by Tapestry New Opera) was a highlight of the 2010 Luminato Festival. Our CBC Radio recording of this major work has recently been leased by the Centrediscs record label and is now available to the public. The release of Dark Star Requiem will receive special notice this fall as we approach World AIDS Day on December 1.

The long legacy of CBC Radio’s development of Canadian composers was a proud one, inspired by The Broadcasting Act and marked by the creation of significant works by distinctive Canadian artists. I was pleased to play a role, along with many gifted colleagues, in that history. Whether the road ahead offers similar promise for future generations of emerging Canadian composers remains to be seen.

David Jaeger is a Toronto-based composer, producer and broadcaster