![]() The development of jazz has largely been fuelled by innovators who blazed new musical trails – Louis Armstrong, Sidney Bechet, Bix Beiderbecke, Duke Ellington, Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young, Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk, Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Bill Evans, Ornette Coleman – to name but an obvious few. These men were so compellingly original that they changed not only how their respective instruments were played, but also how jazz itself would be played or thought of; they altered its overall aesthetic landscape.

The development of jazz has largely been fuelled by innovators who blazed new musical trails – Louis Armstrong, Sidney Bechet, Bix Beiderbecke, Duke Ellington, Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young, Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk, Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Bill Evans, Ornette Coleman – to name but an obvious few. These men were so compellingly original that they changed not only how their respective instruments were played, but also how jazz itself would be played or thought of; they altered its overall aesthetic landscape.

Although jazz has undergone many changes since the 1970s, these have not largely been effected by one or two game-changers such as those mentioned above; it’s been more of a collaborative, evolutionary process rather than one involving radical change. This has not stopped the jazz media from a desperate and misguided search in recent years for the next “new, big thing” – several figures or bands have had this hallowed status conferred upon them, both prematurely and inaccurately.

It’s entirely possible there won’t be a next “new, big thing” in jazz ever again, and it’s just as possible the music doesn’t need one, for several reasons. First, when a field grows stronger and wider from its relatively narrow origins, it becomes harder for any particular individual to dominate it, and this is true with jazz today. Second, jazz now has a sufficient back history and wealth of stylistic influences, morphing and cross-pollinating with increasing speed and frequency, that coming up with anything new in any major sense may no longer be possible, or even necessary. In terms of impact, jazz may never again see the likes of recordings like West End Blues, Ko-Ko or Lonely Woman, each of which set the course for an entire generation or more. But the music will continue to change and grow by mixing various elements of its past with more contemporary influences and with borrowings from other musical styles and cultures, which continue to spin off in new directions. We might call this mixing and matching of the old and new “hybridism.”

This musical cross-breeding can be a mixed blessing. It can yield music that’s confusing and of no particular character, but also music that’s exciting and refreshingly beyond the pigeonholing of genre classification. The difference seems to lie with the quality of the musicians who are playing and whether or not they achieve an integral cohesiveness – some chemistry – while assimilating various musical influences. It’s now possible to go to a live performance by a band and over the course of the evening hear music that blends elements of bebop, free improvisation, the blues, New Orleans trad, R&B, hip-hop, modal and folkloric elements with Latin American, European or other world music influences. The improvisational element and rhythmic vibrancy may mark it as jazz, though you may not know what to call it. And you might not care, because you could well walk away feeling energized and inspired, more open-minded and less concerned with musical labels.

Watts/Goode: Such genre-busting diversity should be expected from the Ernie Watts Quintet featuring Brad Goode and Adrean Farrugia, appearing in the May 21 JPEC (Jazz Performance and Education Centre) concert at the George Weston Recital Hall, as each of the principals has a very eclectic and wide-ranging musical reach.

Watts/Goode: Such genre-busting diversity should be expected from the Ernie Watts Quintet featuring Brad Goode and Adrean Farrugia, appearing in the May 21 JPEC (Jazz Performance and Education Centre) concert at the George Weston Recital Hall, as each of the principals has a very eclectic and wide-ranging musical reach.

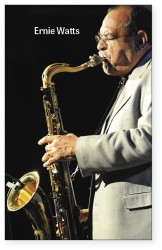

Ernie Watts is a two-time Grammy Award winner who plays soprano, alto and tenor saxophone and flute, but most often tenor. He’s such a versatile musician that he’s been described as an R&B player as often as a jazz one, not entirely without accuracy. He was born on October 23, 1945 in Norfolk, Virginia, and attended the Berklee College of Music on a DownBeat scholarship. He toured for two years with the Buddy Rich band in the mid-1960s and visited Africa on a State Department tour with Oliver Nelson’s band. He settled in Los Angeles during the 1970s, playing tenor for 20 years in The Tonight Show Band, while doing a lot of film and TV work and recording with such as Steely Dan, Frank Zappa, Carole King and many Motown artists, including Marvin Gaye. He joined the Rolling Stones on a 1981 tour, also appearing in their 1982 film Let’s Spend the Night Together.

In the mid-80s, Watts decided to redirect his attention to jazz, his original musical interest since he was 14 and heard John Coltrane on Kind of Blue, an experience he describes as, “It was as though someone put my hand into a light socket.” This was greatly aided when bassist Charlie Haden invited Watts to join his Quartet West band in 1986, along with pianist Alan Broadbent and drummer Billy Higgins (later replaced by Larence Marable.) Watts recorded eight celebrated albums with the group between 1986 and 1999 and it is this association that he’s best known for, locally and internationally. This year his own Flying Dolphin Records label will release Wheel of Time, dedicated to the recently departed and greatly missed bassist.

Watts has a big, soulful sound and a powerhouse attack – though he can also be remarkably lyrical – and his virtuosity never seems to get in the way of his emotional directness. This is because he’s a very committed, very sincere player who means every note he plays regardless of what genre or setting he finds himself in. This sincerity is what makes his versatility successful and is to be expected from a longtime colleague of a musician such as Charle Haden. Perhaps Watts himself sums up his feelings about music best: he believes that it has the power to connect all people, saying that “Music is God singing through us.”

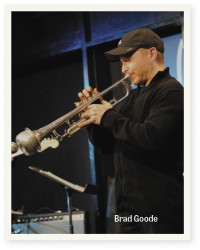

Trumpeter Brad Goode hails from Chicago and is a generation younger than Watts, but shares the saxophonist’s diverse approach to the jazz tradition. He began playing trumpet when he was ten, eventually studying with the great Ellington lead-player, Cat Anderson, and falling under the influence of Dizzy Gillespie and other bebop greats. A neighbour who knew Gillespie took Goode to meet his hero who took one look at Goode’s diminutive stature and red hair and immediately dubbed him “Little Red Rodney.”

Rodney in fact became one of Goode’s musical mentors in Chicago, along with such Windy City stalwarts as Jodie Christian, Eddie Harris, Von Freeman, Ira Sullivan, Eddie DeHaas and others. Goode had the opportunity to play in Chicago house bands, thrown into the front line alongside headliners such as Lee Konitz, Pepper Adams, Jimmy Heath, Joe Henderson and many more. Goode suffered a serious lip injury in 2001 and as part of the arduous process of overcoming this he decided to develop his lead trumpet skills as well as delving into both free and traditional jazz; he now divides his work between lead trumpet and jazz playing. He’s also a fine educator, with professorships at the University of Cincinnati 1997 to 2003 and at the University of Colorado in Boulder, from 2004 to the present.

Rodney in fact became one of Goode’s musical mentors in Chicago, along with such Windy City stalwarts as Jodie Christian, Eddie Harris, Von Freeman, Ira Sullivan, Eddie DeHaas and others. Goode had the opportunity to play in Chicago house bands, thrown into the front line alongside headliners such as Lee Konitz, Pepper Adams, Jimmy Heath, Joe Henderson and many more. Goode suffered a serious lip injury in 2001 and as part of the arduous process of overcoming this he decided to develop his lead trumpet skills as well as delving into both free and traditional jazz; he now divides his work between lead trumpet and jazz playing. He’s also a fine educator, with professorships at the University of Cincinnati 1997 to 2003 and at the University of Colorado in Boulder, from 2004 to the present.

Goode’s playing is marked by a lot of range and technique, a big, lively sound, a wealth of ideas and stylistic openness. Essentially, he’s a modern bebop player who sometimes finds that his musical train of thought doesn’t always fit that style, so he steps outside of it – I’ve heard solos by Goode that remind me of Lee Morgan and Kenny Wheeler all at once. He’s been leading his own quartet since 2010 and in his own words, he’s “attempting to combine my diverse influences and experiences into a style that embraces them all.”

The connecting link between the American front line and the local rhythm team of Neil Swainson and Terry Clarke will be Toronto-based pianist Adrean Farrugia, the only one in the quintet who has played with all its members. His association with Goode dates back to 2003, when the trumpeter was in Toronto to see a prominent doctor about his lip injury and dropped around to sit in at a Rex jam. They had an immediate connection, both musically and personally, and resolved to stay in touch. Despite the geographical distance, they’ve managed to do several dates a year together in various places – Chicago, Toronto, Colorado, and they’ve played together in vocalist Matt Dusk’s band since 2012. Farrugia’s connection to Watts is more recent but no less deep – thanks to Goode, they met and played a concert at the 67th Conference on World Affairs held in Boulder during April of 2015. In Farrugia’s words, “My connection with Ernie almost immediately felt like Yoda/Luke Skywalker. He’s a brilliant, wise and deeply spiritual man.”

It’s fitting that Farrugia should be the linchpin here, because not only is he a scintillating pianist, but also a very empathetic one; his ears and mind are always open. I discovered this the first time I played with him many years ago, on a Saturday afternoon gig at The Pilot Tavern with a quartet led by saxophonist Bob Brough. For some reason the drummer didn’t show up and there wasn’t time to call a replacement, so we decided to go ahead and just play as a trio. Even on an electric keyboard, Adrean’s playing was so rhythmically engaged and propulsive that within a few bars of the first song I completely forgot we had no drummer; the music felt very complete and easy.

Harry “Sweets” Edison once told me, “If I don’t have a good rhythm section I don’t have nothin’ – I’m dead in the water.” Truer words were seldom spoken. Earlier I wrote about the need for cohesion and chemistry and, brilliant as the three principals here may be, they won’t go very far without a good rhythm section. Fortunately, with Neil Swainson playing bass and Terry Clarke on drums, this is not a worry – together they’ve formed a powerful and flexible rhythmic team many times. Neil has been my good friend and colleague since moving to Toronto almost 40 years ago and as far as I’m concerned, you could hardly do better than having him on bass, regardless of the jazz context. The same goes for Clarke, who’s the best overall jazz drummer Canada has produced and remains a dynamo of energy and taste at 71. Enough said.

Rich Brown: In a nice programming touch, Rich Brown and The Abeng will be opening the concert. Brown is one of the most musically authoritative and interesting electric bassists working in jazz today, combining a fat, warm sound, a lyrical and inquisitive approach to soloing and rhythmic mastery. The band takes its name from the African instrument made from a hollowed-out cow horn and plays an exciting brand of groove-oriented jazz, blending African, Latin-Caribbean and contemporary influences. The band consists of the brilliant Kevin Turcotte on trumpet, Luis Deniz on alto saxophone, Stan Fomin on piano and keyboards, Mark Kelso on drums and the leader on electric bass.

This concert promises something of a musical feast which I certainly plan to partake of and I urge others to do so as well. For more information, visit jazz centre.ca

Steve Wallace is a veteran Toronto jazz bassist and writer. He writes about jazz and other subjects on his blog “Steve Wallace: jazz, baseball, life, and other ephemera” at wallacebass.com